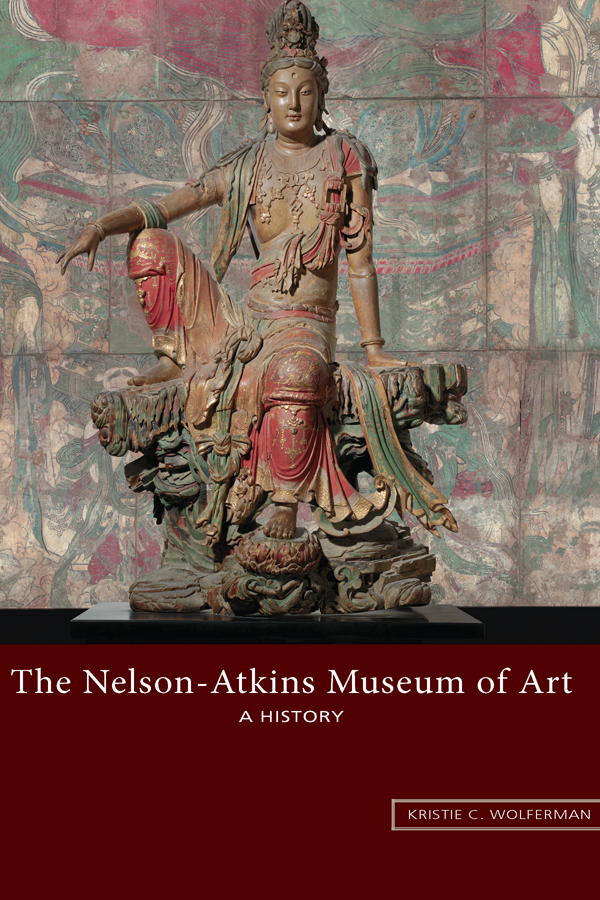

Names: Wolferman, Kristie C., 1948- author.

Title: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art : a history / by Kristie C. Wolferman.

Description: Columbia : University of Missouri Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019025978 (print) | LCCN 2019025979 (ebook) | ISBN 9780826221971 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780826274410 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art--History.

Classification: LCC N582.K3 W66 2020 (print) | LCC N582.K3 (ebook) | DDC 708.1778/411--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019025978

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019025979

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

FOREWORD

A museum should never be finished, but boundless and ever in motion.

Goethe

THE DAY-TO-DAY BUSINESS of running an encyclopedic art museum and welcoming visitors into our galleries is all-consuming. We rarely have a moment to look back and ponder the past. And yet each day here at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, we are building on the decisions and generosity of individuals who, long ago, were deeply committed to creating a place of beauty and distinction in Kansas City.

I am delighted that Kristie Wolferman came to us months ago with the proposal to update her written history of the Nelson-Atkins. We were happy to give her full access to the museums archives and to grant interviews so that she could ask questions about the past and present. Now we can all enjoy the results of her work in this detailed account.

Two observations, upon reading her history:

So many decisions about an art museum for Kansas City were made one hundred years ago, fifty years ago, twenty-five years ago. Today we feel immense gratitude that it all fell into place so beautifullydecisions about where the museum should be located, who would pay for the building, how involved the city would be, and how in the world to buy enough original works of art to fill a future museum.

However, I am also struck by the many threads of conversation from years ago that are still in discussion today. Should the art museum be a civic center? Should the museum sell lesser works of art and acquire finer pieces? How dowe best engage visitors? Who will emerge from the community to support the museum financially?

From my interactions with people across the region, I know they have experienced the Nelson-Atkins in many ways through the years. No one history can capture those diverse perspectives. Attempting to crystallize the past is like chasing the distant horizon; it always escapes.

In spite of that, Wolferman has given us an excellent account of events that unfolded and the people who were involved. It is fascinating to read the names of supporters I have come to know through their children and grandchildren, or from donor lists, or from documents that continue to guide us even now. What a gift!

The impact of the decisions and support of each individual have been immense, and I see it every day. The strong vision then allows us to focus now on the impact we have on each visitor. That is our ultimate goal: to be a museum where the power of art engages the spirit of community.

I like to think that if I could walk through the museum with the decision makers of the past, they would see the significance and immediacy of what they championed long ago and feel great pride!

Julin Zugazagoitia

Menefee D. and Mary Louise Blackwell Director & CEO

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

LETS MAKE HISTORY TOGETHER! Julin Zugazagoitia, the Menefee D. and Mary Louise Blackwell Director and CEO of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, exclaimed when I broached the subject of revising and updating my previous history of the museum. Julins enthusiasm extended to his staff, who supported my research. Special thanks go to Archivist Tara Laver, with whom I spent every Monday and Thursday for more than a year and who made it her mission to find any and all information and images I requested. Gaylord Torrence, Fred and Virginia Merrill Curator of American Indian Art, volunteered his time and expertise to read and edit my text about the Nelson-Atkinss collection and display of Native American art. Catherine Futter, Director of Curatorial Affairs, expertly and promptly answered all my questions related to the collection, while Karen Christiansen, Chief Operating Officer, helped me understand the many changes that have been made in the organization, administration, and operation of the museum since I wrote my previous history. Keith Davis, Senior Curator of Photography, shared his thorough and careful research on the museums amazing photographic collection, and MacKenzie Mallon, Provenance Specialist, checked the history of several works of art. The library staff, headed by Amelia Nelson, and Anne Manning, Director of Education and Interpretation, assisted me as did Stacey Sherman, who handled citations and permissions with alacrity and ease. I also came to know and appreciate Debbie Oliphant, James Hymes, and Robert Gotow in the Security Command Center.

Past staff members, trustees, and friends aided in my research. Many thanks go to Marc Wilson, Director Emeritus, who spent hours answering my innumerable questions and telling me about his experience as Curator of OrientalArt and his twenty-eight years as director of the museum. Ellen Goheen, who served in many different positions at the museum over the course of thirty-one years, graciously and professionally filled in all the gaps in knowledge that I could not find in the trustees minutes or directors files. My talks with Father Thomas Wiederholt, Sarah Ingram-Eiser, Patricia Cleary Miller, Carolyn Kroh, Linda Woodsmall-DeBruce, Tom Bloch, Bruce Mathews, Elliot Rowlands, and Mary Lou Brous broadened my understanding of the social history of the museum while Laura Mombello at the Barstow School and the staff at The Independent helped me find information about the Nelson family.

My interest in writing about the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art began with my masters thesis, so I would again like to thank my advisor in the UMKC history department, the late Richard D. McKinzie, and Lindsay Hughes Cooper, whose remarkable stories about the early days of the museum gave me perspective on what it was like. When Andrew Davidson, editor-in-chief at the University of Missouri Press, suggested that I write a new history of the Nelson-Atkins, I did not realize the extent of this project. I am grateful to Andrew for his confidence and support.

Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family, especially my husband, who have put up with my consuming focus on the stories about the museum.

INTRODUCTION

THE FIRST AMERICAN art museum open to the public was probably the personal gallery of painter Charles Willson Peale, founded in the 1780s, shortly after the American Revolution. Not only did Peales museum display portraits of prominent men painted by Peale and his sons, but his exhibition hall was filled with stuffed animals and birds as well, since Peale was also a taxidermist and naturalist. A few other early museums comprising private collections were conceived shortly after Peales, and some university and college art museums were founded in the first half of the nineteenth century. It was not until after the Civil War, however, that American art museums as we know them today began to proliferate.