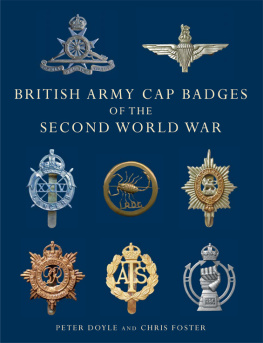

BRITISH ARMY CAP BADGES OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR

PETER DOYLE AND CHRIS FOSTER

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

Soldiers of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), c. 1942. Attached to the Queens Regiment, they wear its cap badge on their service dress tunic, as well as ATS coloured (in dark brown, beech and green) field service caps with brass cap badges.

PREFACE

T HE PURPOSE of this book is to describe and illustrate, for the historian and collector alike, the main types of cap badges worn by the British Army in the Second World War. It is intended as a companion volume to our earlier book, British Army Cap Badges of the First World War, and is illustrative of the great many changes that were experienced by the British Army in the run-up to the second world conflict in a generation.

The army of 193945 was significantly different from that of the First World War; the lessons of the latters closing campaigns underlined the importance of mobility, armour and artillery in conflict, a doctrine that would be adopted by most combative nations in the interwar period. For the British Army, the underemployment of the cavalry arm during the Great War gave birth to a new way of thinking, with the creation of a mobile army, the horsed regiments being transferred to the armoured services, or, in the case of the Yeomanry, the artillery. New equipment, new uniforms and headgear, and new philosophies for the wearing of insignia would all follow suit.

Illustrated in this book are the distinctive insignia of the main units that saw action during the Second World War; limited space precludes the peripherals, but most units are covered: with amalgamations, war-raised units and individual distinctiveness, the topic is a complex one. Wherever possible, we have tried to illustrate genuine badges, though recognising fakes and forgeries is becoming an ever more difficult task. As such, we hope this book provides a reference guide for all who wish to know more about the British Army in the Second Word War, and in particular the actions of their relatives in a war that shaped the world we know today.

Peter Doyle

Chris Foster

Slouch hat belonging to Captain David Jowett of the Royal West African Frontier Force; it is fitted with a chocolate-brown plastic cap badge an economy issue.

Remembrance of war; souvenirs kept by a soldier of the Kings Royal Rifle Corps who served in the Far East with the Fourteenth Army.

Chapter One

THE BRITISH SOLDIER OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR

A T THE CLOSE of the First World War the British Army could claim to be one of the strongest citizen armies ever assembled. Yet, within just twenty years, the victorious army of 1918 had declined to a pale shadow of its former self. With only four regular army battalions that could be mobilised to meet the threat of war, the British government half-heartedly raised new battalions (the Militia) in April 1939, conscripted into the Territorial Army, doubling the armys size to meet the growing threat from mainland Europe. At the outbreak of war, both Militia and Territorials were merged with the regulars to form a major part of the ill-fated British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of 193940.

When the German assault on the western Allies came, on 10 May 1940, its Operation Sichelschnitt stove in the French lines at Sedan and cut the Allied lines in half. With its flanks in the air, the BEF had to retreat in stages with the aim of disembarking from the port of Dunkirk. With a defensive perimeter set up, Operation Dynamo, the rescue of the BEF from France, was put in place on 26 May. Over 350,000 men would be rescued from the beaches leaving behind ample evidence of their hurried departure. The miracle of Dunkirk was complete by 4 June 1940. And though the proposed German invasion of Britain of 1940 was abandoned, throughout 1941 and into 1942 the British were to suffer severe tests of arms by the Germans both in Greece and Crete.

In North Africa, the Western Desert was the perfect stage for the armoured battles that raged in 19412, fought for possession of key towns in Libya and Egypt. With Montgomerys defeat of Rommel at El Alamein in November 1942, the balance would move in the Allies favour, and the Germans would finally be driven out of North Africa by May 1943, opening the way for the Allied invasion of Italy, through Sicily, in July 1943. The fight up the spine of Italy would be long and bitter, from one fiercely defended strongpoint to another, and would not be over until May 1945.

With the war still raging in Italy, a new front opened in northern Europe the greatest amphibious assault ever planned. Integral to the invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944 were British armoured and infantry divisions, and special and airborne forces. From their landings, the British and Canadians would form the hinge of the swinging door that would swing the front around and take on the Germans on a broad front, pushing them back through occupied France. After difficult times, by 20 August the way was clear to advance on Berlin, just as the Russians were doing in the east. Paris fell to the Allies on 24 August, Brussels on 4 September. There were tactical gambles on both sides Montgomerys Operation Market Garden of 20 September 1944, intended to capture intact an array of bridges across river obstacles in the way of the advance into Germany, and the crossing of the Rhine; and Hitlers Operation Wacht am Rhein in the Ardennes during the winter of 19445, intended to punch a hole through the Allied lines and separate the British and Canadians from the Americans. Both gambles failed. But on 5 May 1945 all German forces in north-west Europe had been surrendered to Montgomery at his headquarters at Lneberg Heath, near Hamburg, and by 7 May all German forces followed suit. The British Army had once again reached a peak of effectiveness.

Players cigarette card showing the uniform of the territorial soldier in c. 1939.

Fusilier Tom Stafford of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers pictured with a friend in Egypt, c. 1941.

Left behind debris of the hurried evacuation of the BEF from Dunkirk in May and June 1940.