I n 1826, when English scientist James Smithson wrote his will and bequeathed his fortune to the United States to establish an institution dedicated to the of knowledge, he had high hopes that his gift was in good hands. I do not think the American people and the Smithsonian, as the trustees of that gift, have let him down. The Smithsonian stands for what is best about our country, through its research in science, history, art, and culture; through its care of the natural and cultural treasures of this planet; and through its work to educate tens of millions yearly during visits to its museums and every minute of the day via its digital outreach to the world.

Early on, the Smithsonian began acquiring the artifacts and artworks, the archives and documents, that represented Americas national identityits heritage and its accomplishments, its deep history and most creative aspirations. As the collections have grown, it has become a repository of who we are as a people.

The Smithsonian not only maintains our collective memory but also keeps alive, through research and education, an understanding of our accomplishments and ideals, our struggles and innovations, represented by the most comprehensive collection of objects in the world. Understanding our past is the only way to build a foundation for our future.

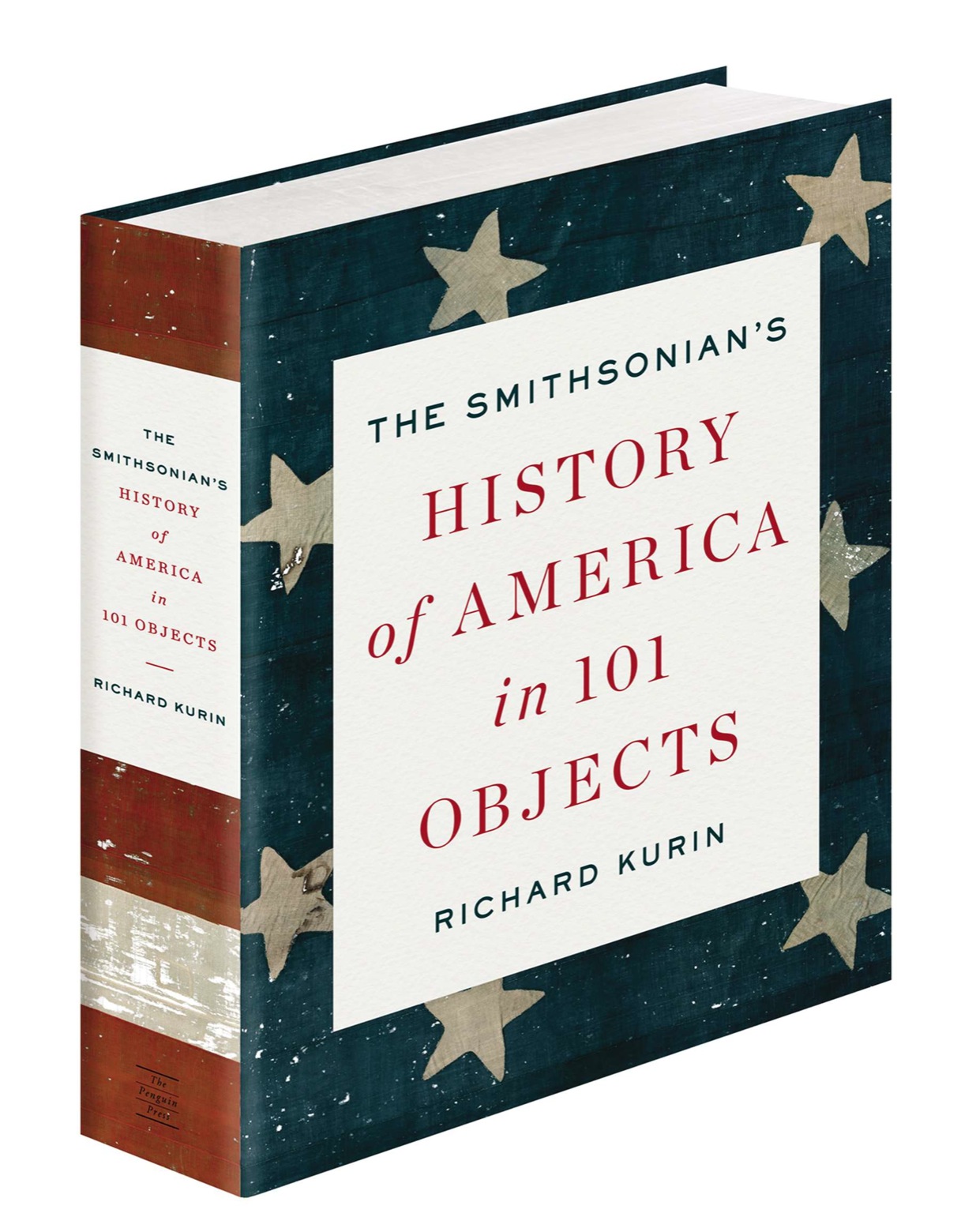

In this marvelous book, Richard Kurin, one of the Smithsonians living treasures and my colleague, uses 101 key objects of American history in the Institutions collections to tell the story of our country in a robust, engaging, and entertaining fashion. His account shows us why these objects continue to attract some 30 million domestic and international visitors a year to our museums, and more than 100 million onlinemaking it by far the most visited museum in the world and one cherished by generations of Americans and appreciated by people around the globe.

PREFACE

RICHARD KURIN,

Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture,

Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C.

T his book has been a joy to write, and I have learned so much in doing so.

The project was inspired by Neil MacGregors outstanding A History of the World in 100 Objects, using the collection of the British Museum. That book proved to be enormously popular, and has provided an excellent introduction for many to appreciate the worlds treasures, and the processes, societies, and people they represent. Scott Moyers, publisher of Penguin Press, publishing colleague Gail Ross, and I took up the idea of a book examining American history through the treasured objects of the Smithsonian Institution.

This book is written for a broad audience rather than for the professional historian or the scholar. I hope the stories about these 101 objects from the Smithsonians collections will inspire readers to learn more of our nations history. I also hope the book encourages acts of good citizenshipsomething so basic in the American experience.

No one could write this book alonethe scope of American history is too broad and the detailed knowledge required too deep. Furthermore, each of these objects has stories to tell not only about its place in history but also about how it came to the Smithsonian, and how it has been studied, displayed, and understood. Hence I have relied upon a stellar team of colleagues to help me.

Foremost has been a team of research scholars exceptionally well qualified and accomplished. Heather Ewing, a notable author with great knowledge of the Smithsonian, was a critical partner throughout the project. Helpful, supportive, and challenging, she coordinated the team. Laurie Ossman, an expert in architectural history and material culture, and Brian Daniels, an expert in American history and cultural heritageboth of them strong and experienced in museum studiesplayed major roles in guiding, researching, and shaping the book. Rounding out the research team, Veronica Conkling, a specialist in the history of decorative arts and museum studies, helped reference sources, track down objects, secure permissions for the use of photographs, and perform numerous other organizational tasks. Tatum Willis, a history student at Yale University who served as an intern, and my law school daughter Jaclyn Kurin helped develop the background material needed for the research.

The collections of the Smithsonian have dedicated stewards, curators, and fellows who study the objects, conservators who care for them physically, and managers and archivists who keep track of them and ensure their safety, security, and accessibility. Photographers document the objects, and Webmasters and technicians digitize and distribute information about them. Thanks to the cooperation of the Smithsonians directors, with whom I am proud to serve, more than one hundred of these specialists were involved in the project and gave me and the research team information and access, wisdom and guidance, advice and more advice, about each and every object. Mostly I took it, though sometimes interpretations and approaches diverged. Among expert advisers are those listed below, by the museum or research center of the Smithsonian.

Anacostia Community Museum: Director, Camille Akeju; Joshua M. Gorman, Portia James, Gail Lowe;

Archives of American Art: Director, Katherine Haw; Acting Director, Liza Kirwin; Mary Savig;

Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage: Director, Michael Mason; Director, Daniel Sheehy; Olivia Cadaval, Marjorie Hunt, Sojin Kim, Jeff Place, Arlene Reiniger, Stephanie Smith, D. A. Sonneborn;

Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum: Director, Caroline Baumann; Demian Cacciolo, Sarah Coffin, Caitlin Condell, Gail Davidson, Gregory Herringshaw, Cara McCarty, Matilda McQuaid, Janice Slivko, Stephen Van Dyk, Nate Wilcox;