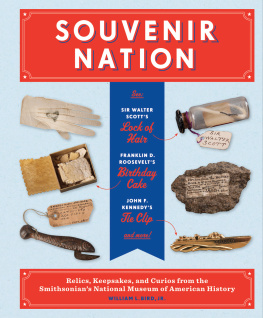

he objects pictured and described here are from the collection of the Division of Political History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. The museums history collection originated in 1883, when the US government transferred historical artifacts from the US Patent Office to the new National Museum on the Mall in Washington. As the collection grew by donation, specialized collecting units were established, leaving unclaimed objects in the original history collection.

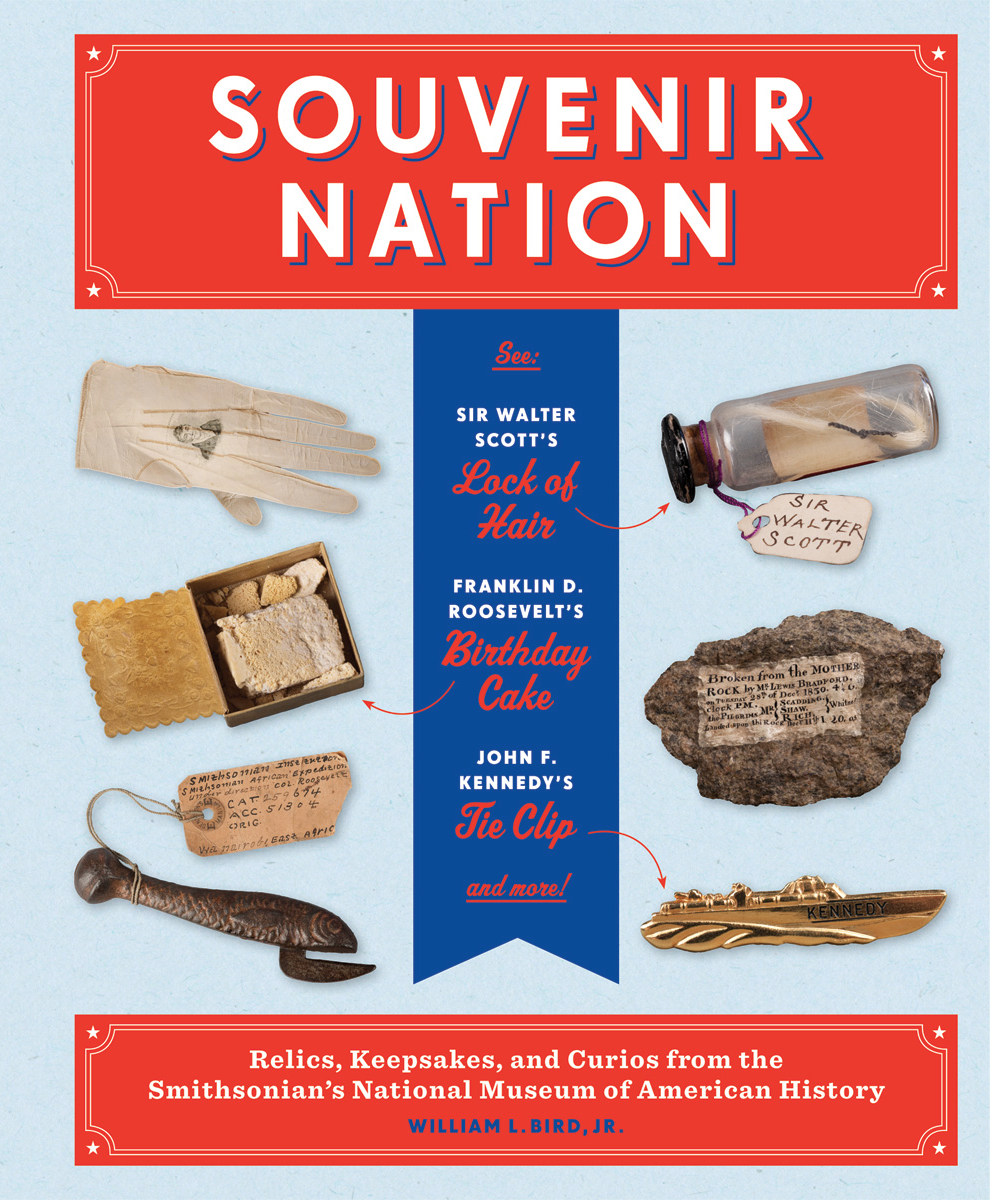

While these are typically described as relics or association objects, those that I find most interesting suggest the alternate designation of souvenir. Most are smallthe kind of thing that could have been carried away in a pocket or a purse. Many are piecesfragments, reallyof much larger things of intense personal and historical interest that were held closely by their eventual donors. Despite their keepsake status, most are nondescript and would likely have been overlooked or lost if not for an accompanying note. These lucky objects arrived at the museum with their labels already written.

any years ago, while I was working for the National Museum of American History on an exhibit about George Washington, a chance encounter with a relic sparked my curiosity about the things that people save. For thisexhibit, the museum had arranged to borrow a group of Washington-related items from the Mount Vernon Ladies Association. One of the objects that came my way was a small piece of wood pasted with a handwritten paper note. The wood and note lived in a plastic sandwich bag closed with a red seal. The inscription read:

Piece of the triumphal arch under which George Washington passed in Trenton, on his way to New York to be inaugurated first President of the United States. Presented by Chas. Hunt. Trenton. Oct. 1891.

Who was Charles Hunt? A Trenton employee of the Pennsylvania Railroad. And what was happening at Trenton in October 1891? The construction of the Trenton Battle Monument commemorating the first Battle of Trenton, a 1776 Revolutionary War victory for the Americans. Aside from such questions of attribution, this inscribed wooden fragment seemed in its very existence a triumpha triumphal souvenir.

Purchased casually from a postcard rack or gift shop, the souvenirs we collect today are the material descendants of earlier objects that reveal how Americans thought about the past and how it would be saved. Like the fragment of Trentons triumphal arch, these early souvenirs are ordinary objects of extraordinary circumstance. They may celebrate an experience, an achievement, or nothing of any obvious significance, for their only allegiance is to memory. They might be known as relics , mementos , keepsakes , or curios ; each term has specific connotations. A relic, for example, may be viewed as magical or mystical, but its primary power lies in the perception that it is actual and real. A keepsake or memento usually is invested with personal, emotional qualities. The term curio , derived from curiosity , refers to a thing of inherent interest. Often featured as attractions in nineteenth-century museums, curios bridged the distinctions between education and entertainment. Whether a relic, memento, keepsake, or curio, each item acquired significance from the act of taking that made it a souvenir.

The term historical artifact has replaced the word relic in todays museum nomenclature, and souvenirs are no longer taken but purchased. This long transition in curatorial thought and practice can be traced through the story of the Smithsonians origins.

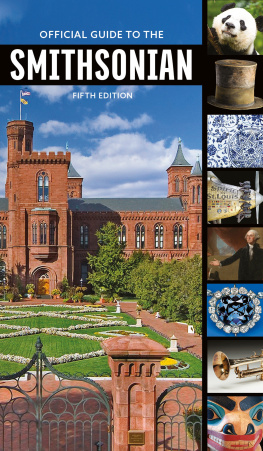

The original forebearer of todays National Museum of American History was the United States National Museum, organized under the administrative umbrella of the Smithsonian in the nineteenth century. The creation of an emergent class of American professional scientists, it was not initially known for its collection of historical relics. Even before the Smithsonian Museum was first founded in the 1850s, relics had taken a back seat to exploration expedition specimens in the collections of its predecessor, the government museum at the US Patent Office. Before they were at last packed off to the National Museum in 1883, the Patent Offices relics were displayed in the manner of a cabinet of curiosities, led by George Washingtons dress uniform and household effects from his estate, Mount Vernon [ Fig. 1 ].

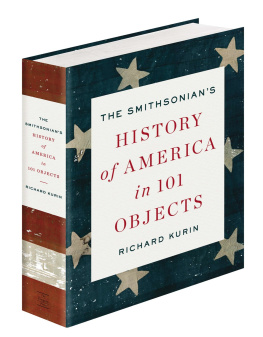

Heretofore, the historical past had been preserved through artwork: paintings,sculpture, monuments, medals, and coins representing heroic figures and events. Though seldom accorded the value of such fine-art pieces, the souvenir-relic sprang from the same historical impulse. By the 1920s the National Museums Division of History included a kid glove imprinted with a likeness of the Marquis de Lafayette;

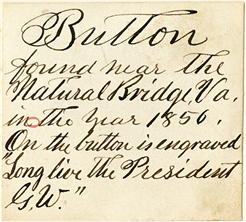

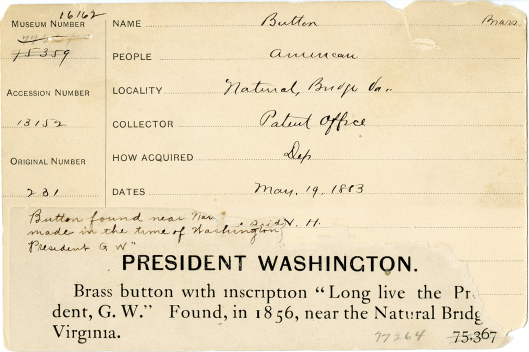

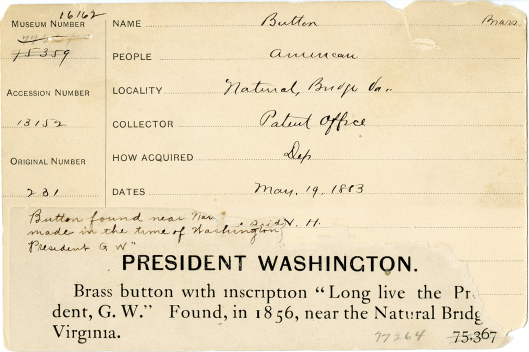

Fig. 1

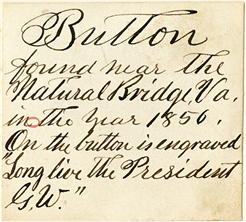

The Patent Offices National Gallery displayed this brass, engraved clothing button made in 1789 to celebrate George Washingtons inauguration. One of several GW designs made at the time, this button has a linked states pattern encircling a center inscription: Long Live the PresidentGW. The button was doubly triumphant for having been lost and found near Natural Bridge, Virginia, in 1856, a fact duly noted on its museum label.

a tiny piece of the French Bastille; a fragment of mosaic pavement from the palace of the Roman emperor Tiberius; a white dish towel used as the flag of truce to end the American Civil War at Appomattox Court House, Virginia; the table and chairs used while negotiating the terms of General Robert E. Lees surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant; and a chip of wood from a railroad tie at Promontory, Utah. With the exception of the Lafayette glove, there was nothing remarkable about the appearance of any of them. Such things might have been lost for lack of a distinguishing mark or the explanation of an accompanying note or letter [ Fig. 2 ].

The practice of attaching notes to souvenirs attests to the social value of objects whose chain of possessiontheir provenancewas all. The most celebrated nineteenth-century example of the note as affidavit is the one that Thomas Jefferson fixed to the portable desk of his own design on which he composed the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson pasted this note to the surface of his desks writing box in 1825 before sending it off as a wedding present to his niece and her new husband [ Fig. 3 ]. Jeffersons note explains the circumstances of the desk and imagines its future as a revolutionary relic: the desk might one day be carried in the procession of our nations birthday, as the relics of the Saints are in those of the Church. It is worth noting that six years earlier, Jefferson had compiled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth , excerpting moral morsels from the Gospels to make a book of teachings free of angels, saints, and miracles.