Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Text 2019 by Lonnie G. Bunch III and Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P.O. Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Creative Director: Jody Billert

Senior Editor: Christina Wiginton

Editorial Assistant: Jaime Schwender

Edited by Evie Righter

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

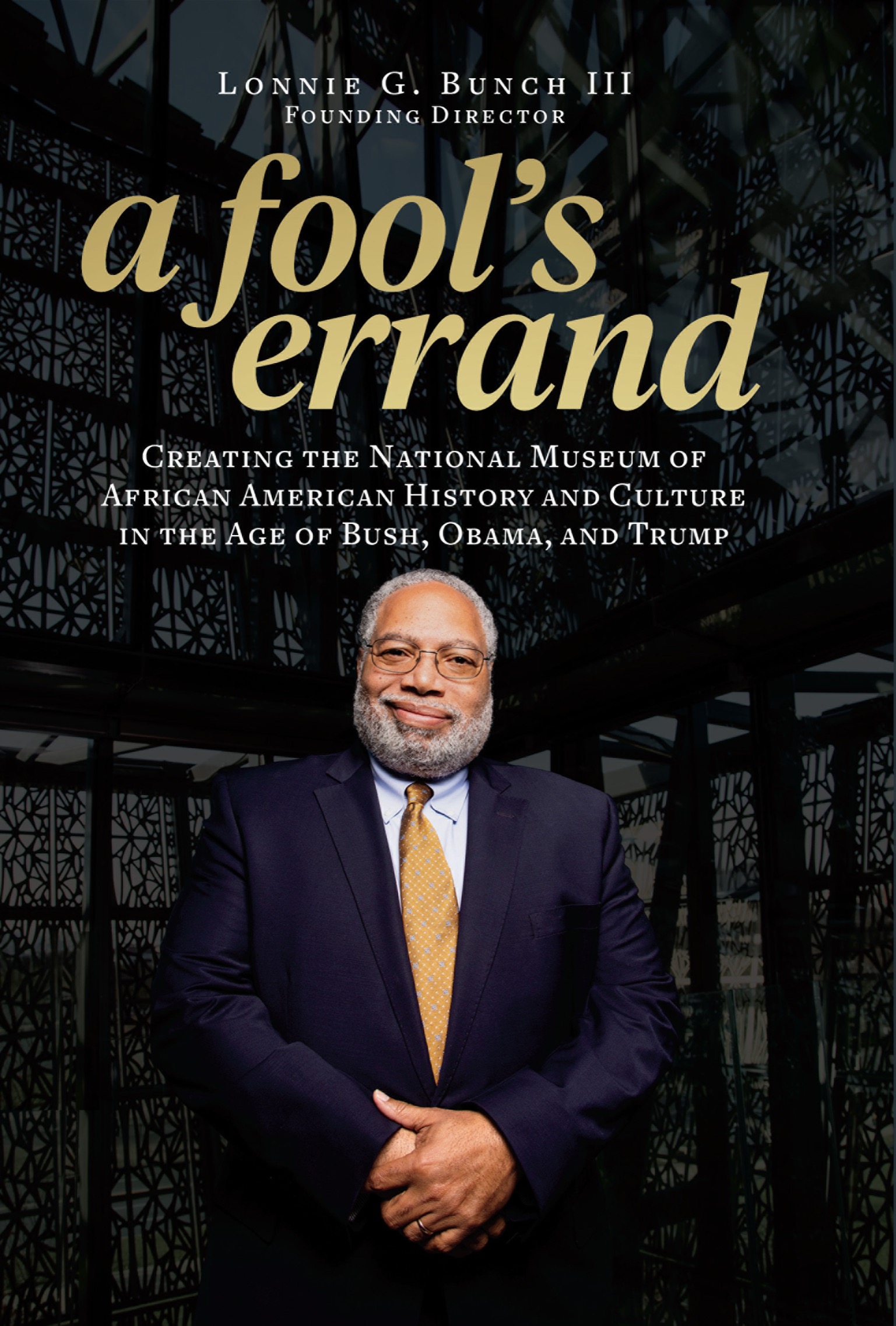

Names: Bunch, Lonnie G., author.

Title: A fools errand : creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the age of Bush, Obama, and Trump / Lonnie G. Bunch III.

Description: Washington, DC : Smithsonian Books, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019001828 | ISBN 9781588346681 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781588346773 (ebk.)

Subjects: LCSH: National Museum of African American History and Culture (U.S.) | African AmericansMuseumsWashington (D.C.)Planning. | MuseumsSocial aspectsUnited States. | MuseumsWashington (D.C.)Planning.

Classification: LCC E185.53.W3 N383 2019 | DDC 069.09753dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019001828

Ebook ISBN9781588346773

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as seen after each caption. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually, or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

v5.4

a

This book is dedicated to my colleagues at the National Museum of African American History and Culture and to the staff of the Smithsonian Institution, both of whose commitment to excellence, to service, to scholarship, and to the American public is often unnoticed but greatly appreciated by me.

And to my grandchildren, Harper Grace and Myles, in the hope that they will live in an America worthy of their dreams.

CONTENTS

The National Museum of African American History and Culture at twilight on a summer evening, with the Washington Monument in the distance. PHOTOGRAPH BY ALAN KARCHMER

What Happens to a Dream Deferred?

Langston Hughes, 1951

Success is not final, failure is not fatal: It is the courage to continue that counts

W INSTON C HURCHILL

My mantra for that day, September 24, 2016, was whatever you do, dont trip and fall. After eleven years of struggling, believing, convincing others to believe, threading the political needle, and surviving nearly 495 fundraising sojourns, tens of thousands had gathered on the National Mall to bear witness to the opening dedication ceremony of the Smithsonian Institutions National Museum of African American History and Culture. Sitting under the museums porch on a stage with President and Mrs. Obama, former President Bush and First Lady Laura Bush seated just in front of me, Chief Justice John Roberts, the Chancellor of the Smithsonian across the stage from me, the American icon John Lewis next to me, and an array of senior Smithsonian officials everywhere, I finally let myself accept the enormity of what we had accomplished and what the opening of a museum intended to help America confront its tortured racial past could mean to a nation weary of a divisive presidential campaign, and a country still struggling to define its identity in the twenty-first century. To control my nerves, I forced myself to take in the crowds, the more than 7,000 VIPs (in other words, their support had earned them chairs) and the multitude who watched the ceremony on Jumbotrons from the hillside and from the grounds of the Washington Monument. I realized how much I did not want this moment to end. I did not want to forget a single second because while the success of this endeavor was due to the efforts of hundreds, the vision and the stress of leadership was mine alone.

I was gratified to see an audience more representative of Americas diversity than what one commonly experiences in Washington. The crowd, while well represented by those usually associated with this company townformer President Bill Clinton, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, Nancy Pelosi, Minority leaderalso included museum supporters and visitors who just wanted to experience this moment. It felt more like a mini-Obama-like inauguration rather than the celebration of a museum opening. Even the speeches soared to match the significance of the moment. President Bush delivered what I consider to be the best speech of his career, reminding us that slavery was Americas original sin and that a great nation embraces its past rather than hides from its moments of pain or evil.

I was so moved by President Obama who could not conceal his emotions as he framed the African American experience as not a separate or shameful past, but a key part of who we are as Americans. And Congressman John Lewis, standing with the moral authority of someone beaten but not broken during the Civil Rights Movement, as he sought to help a nation bind its racial wounds using the museum as part of the healing balm. What lightened my mood and lessened my fear was listening to Patti LaBelle sing the song I requested, Sam Cookes A Change Is Gonna Come. Her rendition reminded us that even in the most difficult time, change was possible. Her closing line that the change would be Hillary was embraced by the audience, especially Bill Clinton who leaped from his seat, would ultimately be proven wrong only a few weeks later.

As the Voice of God called me to speak, all I could think about was how Congressman Lewiss feet were blocking my path to the podium. After eleven years, all I could do was pray, please Lonnie, dont trip because that is all that anyone would remember. I managed to arrive at the podium, and I was choked with emotion and gripped with fear. And, once again, I was overwhelmed when I saw so many people standing, applauding, and calling out my name. At that moment, my thoughts turned to my father and grandfather, both named Lonnie. My grandfather, who began life as a sharecropper on the Perry Plantation outside of Raleigh, North Carolina, had sparked my love of history, and my Dad, a scientist and teacher whose race had limited his career options, had prepared me to be a black man in America. My mind drifted back over the years it had taken me to arrive at this setting. I could never have imagined all the experiences, disappointments, times of great joy, all the visits, and all the people I would encounter. Most importantly, I felt the spirit of my namesakes, the other Lonnie Bunchs, because in many ways the crowd was honoring them too, their struggles and their lives, as much as they were recognizing me. I could not believe that the one hundred-year-long journeyand my own eleven-year sojournto create a black presence on the National Mall was over.