Contents

Frontispiece.

Immokalee Statue of Liberty, created by Kat Rodriguez, 2000. This rendition of the Statue of Liberty is holding a tomato in her right hand instead of a torch, and a tomato basket in her left hand instead of a tablet. The papier-mch and mixed-media sculpture linked the struggles of migrant farm workers with a powerful symbol of immigration to the United States. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, gift of Coalition of Immokalee Workers.

Published by

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SCHOLARLY PRESS

P.O. Box 37012, MRC 957

Washington, D.C. 20013-7012

www.scholarlypress.si.edu

Copyright 2017 by Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

All photos by Jaclyn Nash unless otherwise credited.

All images courtesy of the National Museum of American History unless otherwise credited.

).

National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (see Lilienfeld, ).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Salazar-Porzio, Margaret, editor. | Troyano, Joan Fragaszy, editor. | Safranek, Lauren. | Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, publisher.

Title: Many voices, one nation : material culture reflections on race and migration in the United States / edited by Margaret Salazar-Porzio and Joan Fragaszy Troyano, with Lauren Safranek.

Other titles: Smithsonian contribution to knowledge.

Description: Washington, D.C. : Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2017. | Series: A Smithsonian contribution to knowledge. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016040060 | ISBN 9781944466091 (cloth) | ISBN 9781944466114 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: MinoritiesUnited StatesHistory. | ImmigrantsUnited StatesHistory. | United StatesEmigration and immigrationHistory. | United StatesRace relationsHistory. | United StatesSocial life and customs. | United StatesCivilization.

Classification: LCC E184.A1 A288 2017 | DDC 305.800973dc23 | SUDOC SI 1.60:M 11

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016040060

ISBN9781944466091 (cloth)

Ebook ISBN9781944466114

v4.1

Contents

John L. Gray

Gary Gerstle

Margaret Salazar-Porzio and Joan Fragaszy Troyano

Barbara Clark Smith

Ramn A. Gutirrez

Christopher Lindsay Turner

John Kuo Wei Tchen

Bonnie Campbell Lilienfeld

Nancy Davis

Kym Rice

Alan M. Kraut

Fath Davis Ruffins

Joan Fragaszy Troyano and Debbie Schaefer-Jacobs

Davarian L. Baldwin

Sojin Kim

Margaret Salazar-Porzio

L. Stephen Velasquez

Masum Momaya

Jason De Len

Scott Kurashige

Welcome

The Great Seal of the United States contains the 13-letter Latin phrase E Pluribus Unum, which translates to Out of Many, One. And when we think of the One, we think of the one nation that has been forged from the Many.

Many Voices, One Nation is a historic and dynamic look at the peopling of our country. The National Museum of American History is dedicated to using our unparalleled collection of national treasures to help us understand the past in order to make sense of the present and shape a more humane future. The role of the National Museum is to tell the story of how our people have come together to participate in the growth and development of an ever-evolving national narrative. So how do we share stories that will foster greater understanding, empathy, and connection among the many and the one?

This publication and exhibition highlight the Smithsonians greatest strengths. We draw upon the collections and expertise of colleagues across the Institution. As a nexus between some of the nations foremost scholars and the American people, we are very pleased to feature contributors from academic institutions across the country.

We invite you to explore the many stories within our shared history and discover the commonalities that bring us together as a people.

John L. Gray

Director

National Museum of American History

Foreword

Gary Gerstle

The peopling of America is one of the most vivid and consequential stories in the countrys history. Across more than five centuries, somewhere between 70 and 80 million individuals journeyed as free people or as unfree laborers to what would become the United States. Millions more became part of the United States as a result of the new republics expansion and conquest of land that had belonged to other empires and nations. Over time, the major movements of people and redrawing of borders rendered the United States as heterogeneous a society as any on the planet, home to a remarkable diversity of nationalities, races, and ethnicities. How, exactly, does one tell this American story of movement, exchange, and conflict comprehensively? How can one do justice to all the groups who have become part of America, to their experiences here, and to their encounters with each other?

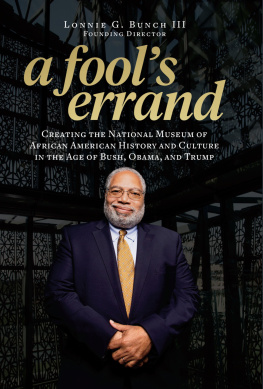

The Smithsonian has told portions of this story, and done so brilliantly, in numerous exhibits focused on specific groups of migrants and minorities, first in the National Museum of American History and the National Museum of Natural History, and later in the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. But the last effort by the Smithsonian to grasp the peopling story in its entirety occurred a long time agoin 1976, the year of the Bicentennial, when A Nation of Nations debuted at the National Museum of History and Technology, the forerunner of todays National Museum of American History. I was finishing college and preparing for graduate school when I first visited A Nation of Nations. The exhibit enthralled me, and I returned to see it again and again. I did not yet know that I would spend a good part of my career studying immigration history, but, in retrospect, my engagement with that exhibit was an early sign of a subject that would sustain my interest across decades.

A Nation of Nations successfully distilled the knowledge of immigration history as it existed at that time, and conveyed it through the display and interrogation of objects: clothing, paintings, ceremonial objects, tools, weapons, inventions, a classroom, and a World War II army bunk all appeared in the exhibit. In the wake of the civil rights movement, no credible effort to represent the past could celebrate America as a place of unmitigated freedom, or as a place where everyone had melded into one undifferentiated shape.