Simona Pilolla 2/Shutterstock

Contents

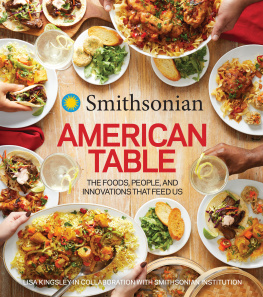

Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are, the French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin famously wrote. How and what we feed ourselves is ever evolving due to migration; climate change; political, economic, and environmental movements and events; new technologies; and human creativity and innovation. Food offers a powerful lens through which we can increase understanding of science, art, history, and culture.

A search across the Smithsonian Institutions collections for the word food yields tens of thousands of results. That number includes exhibitions, stories, historical narratives and interviews, events, film and video, and objects ranging from cooking utensils to serving vessels to packaging to cookbooks to restaurant menus and other ephemeraand much, much more.

Across the wide breadth of its museums, research centers, cultural centers, and programming, the Smithsonian tells the ongoing stories of the American tableand those of the American people. The American Food History Project at the National Museum of American History has taken a leading role in this work. For more than 25 years, the project has used the power of food and drink to engage audiences in conversations about culture, technology, labor, memory, and morethe ingredients of our daily sustenance. With a deeper understanding of the history of food in the United States, we can come to the table to create a more just, sustainable present and future.

American Table is a multifaceted look at how place, historical events, and diverse people have influenced how and what we eat in the United States. Its not just the story of those who have pushed the culinary arts forward, but also of activists, scholars, inventors, and everyday people who are opening our eyes to history and trying to make change in the present to better their communities. Learn how Native Americans have been working to reclaim their traditional foodways and achieve food sovereignty to improve the health of their communities, how a Black female chef gained renowned and culinary influence by showcasing her skills on her own television show in Jim Crowera New Orleans, and how everything from fondue to Jell-O salads to pumpkin spice (even in hummus) became national obsessions.

While this book highlights in snapshots many stories around food, it is not even a fraction of the whole narrative.

We hope reading it spurs more exploration of the rich tapestry of the American storythe foods, people, and innovations that have fed us through history to the present, and those who will feed us in the future.

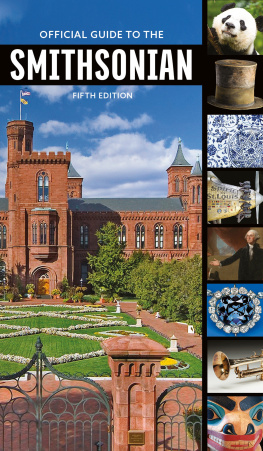

The Smithsonian Institution Building, popularly known as the Castle, is an iconic symbol of the museum. It served as the home and office of the first Secretary of the Smithsonian, Joseph Henry.

Ratov Maxim/Shutterstock

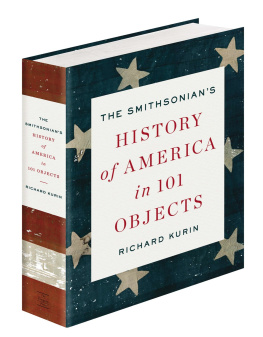

For more than 175 years, the Smithsonian Institution has sought to preserve, study, and increase understanding of science, history, art, and culture. Across its museums, more than 156 million objects help visitorsin person, in publications, through programming, and onlineexplore who we are, where weve been, and where were headed.

An Evolving Endeavor

History is what happened in the past, but it informs and shapes the present. In that spirit, the Smithsonian constantly seeks to increase understanding of science, history, art, and culture among all Americans and the ability of all to have their story told.

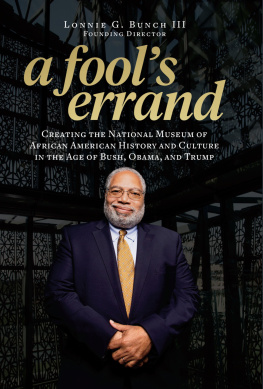

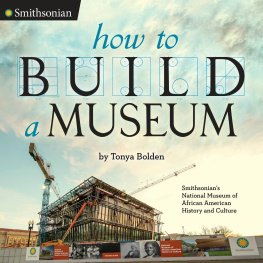

It is an ongoing process. In 2004, the National Museum of the American Indian opened its doors to the public, and in 2016, the National Museum of African American History & Culture did the same. In 2020, Congress appropriated funds to create two new museumsthe National Museum of the American Latino and the American Womens History Museum.

It is something of a quirk of history that the Smithsonian was established not by an American, but by a British scientist named James Smithson (17651829). Smithson left his estate to the United States to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.

Congress authorized acceptance of the Smithson bequest on July 1, 1836. After a decade of debating, on August 10, 1846, the U.S. Senate passed the act organizing the Smithsonian Institution, which was signed into law by President James K. Polk.

Once established, the Smithsonian became part of the process of developing an American national identityan identity rooted in exploration, innovation, and a unique American style. That process continues today as the Smithsonian looks toward the future.

A Lasting Legacy

Smithson was the child of a wealthy Englishman. He traveled much during his life but never set foot on American soil. Why, then, would he decide to give the entirety of his sizable estatewhich totaled half a million dollars, or 1.5 percent of the United States entire federal budget at the timeto a country that was foreign to him?

Some speculate that he was inspired by the United States experiment with democracy. Others attribute his philanthropy to ideals inspired by such organizations as the Royal Institution, which was dedicated to using scientific knowledge to improve human conditions. Smithson never wrote about or discussed his bequest with friends or colleagues, but his gift has had a profound impact on the arts, humanities, and sciences in the United States.

Since its founding more than 175 years ago, the Smithsonian has become the worlds largest museum, education, and research complex, with 19 museums that contain more than 156 million objects, the National Zoo, and nine research facilities.

RozenskiP/Shutterstock

An early 19th-century illustration by Seth Eastman features Ojibwe women gathering wild rice in present-day Minnesota.

North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy Stock Photo

Left to right: Tom Reichner/Shutterstock; Brent Hofacker/Shutterstock; Dudarev Mikhail/Shutterstock

Where we live shapes what we eat. The environment, available foodstuffs, and migration have determined the diets of Indigenous peoples, colonizers, immigrantsand their descendants. From the wild rice harvest by the Ojibwe of Minnesota since precolonial times to the lemongrass- and fish sauceinfused crawfish boil that bubbled up with the arrival of refugees from Southeast Asia to Houston, there is both continuity and creativity in the story of American food.

First People, First Foods

Mtsaride/Shutterstock

For thousands of years before Europeans arrived, Native people had healthful diets based on foods they hunted, gathered, fished, and grew. Colonization disrupted that, but a movementthat of food sovereigntyseeks to reclaim and return to those holistic and culturally significant foodways. Food sovereignty, writes activist and author Winona LaDuke in the foreword to