Acknowledgments

My first acknowledgment of indebtedness goes to my advisors and teachers at Princeton. Earliest on, Diana Fuss led me to think through objects and things. She gave me many other things as an advisor, including the courage for patience, clarity, and difficult questions. As my main supervisor, Claudia L. Johnson went beyond her call of duty in reading just about every single incarnation of the book. Her advice has always been direct and illuminating, and her deep support continues to carry me through many tricky passages. Jonathan Lamb was dedicated and expansive in his advisory role; he readily loaded me with books, sources, and all the time I needed for his counsel. April Alliston was the first teacher to galvanize eighteenth-century studies for me. I am grateful for her probing and judicious comments on my writing, the excitement she passed on to me over questions about mimesis, character and verisimilitude, and above all her most loyal support and friendship. Joanna Picciotto taught me everything I know about seventeenth-century England. Being her preceptor for her undergraduate seminar gave me an opportunity to learn from her dazzling gifts in teaching, scholarship, and friendship. I am grateful to Oliver Arnold for taking an early interest in my work. He was the first to encourage me to find promise in dolls. I am lucky to have had such formidably talented scholars as my mentors.

My teachers at Bryn Mawr, Jane Hedley and Carol Bernstein, first taught me how to trace the beauty of ideasalways closelyand love rigor as its own reward. I could not have predicted how long it would take for me to get to thank them in this way. My colleagues at McMaster University, David Clark, Henry Giroux, Melinda Gough, Jacques Khalip, and Susan Searls Giroux have been generous in sharing with me their wisdom, time, support, and candor. Alicia Kerfoot, an inspiring doctoral supervisee, single-handedly helped me with the intimidating chore of obtaining permissions and reproductions for illustrations in this book. Antoinette Somo took me under her able wing and made many gestures of loyalty and support that I will always remember. The members of my graduate seminar The Eighteenth-Century Novel, Melissa Carroll, Ailsa Kay, Amanda Spina, Pouria Taghipour Tabrizi, and Emily West were passionate readers and interlocutors, bringing me good cheer during an important stage of writing this book. The many colleagues at Vassar who have taken the time to give me much-appreciated support, guidance and good will include Mark Amodio, Peter Antelyes, Beth Darlington, Bob DeMaria, Don Foster, Wendy Graham, Michael Joyce, Jean Kane, Paul Kane, Dorothy Kim, Zoltan Markus, Dan Peck, Paul Russell and Susan Zlotnick. William Germano helped me at a crucial point in getting my book proposal off the ground. I can only wish to write with his zest and style, as well as fulfill the standards of his editorial vision. Norris Pope, the original acquiring editor for this book at Stanford University Press, has been patient, gentlemanly, and attentive. Working with him, Emily-Jane Cohen, and Sarah Crane Newman has been a pleasure. My two readers at Stanford, David Porter and Peter Schwenger, helped bring closure to this project with their detailed and encouraging reports. David Porter has been especially gracious to me as a senior eighteenth-century scholar.

I am blessed to be working in a field with many other gifted and generous scholars. I owe Farid Azfar, George Boulukos, Jenny Davidson, Lynn Festa, Deidre Lynch and Lisa OConnell not only for their inspiring models of scholarship and writing, but also for their steadfastness and advice, and readiness for a good meal. Erin Mackie and Jonathan Sheehan displayed true nobility of character in reading and commenting on a very early version of my manuscript. Joseph Drury read the manuscript at a later stage and provided helpful and insightful commentary, too. John Brewer walked with me through many dilemmas, as well as hills in Hollywood. Friends situated in other areas of expertise have been no less crucial for their unfailing loyalty and sustenance. Tamara Ketabgian has been an intellectual companion and friend since graduate school. I have benefited from her reading of my work, and from the pleasure of reading hers. She and Daniel Youd have been there for meshowing up whenever it matteredin ways I will always remember. Ellen Wayland-Smith has been deep and true as a friend in counting my successes as dear to herself, too. I look forward to seeing her book in print too. Ed Park gave me the title for my last chapter, and earliest on, excitement for objects and machines of the mind. Sakhr Tarikis care, devotion and integrity have helped me stay true to my best interests.

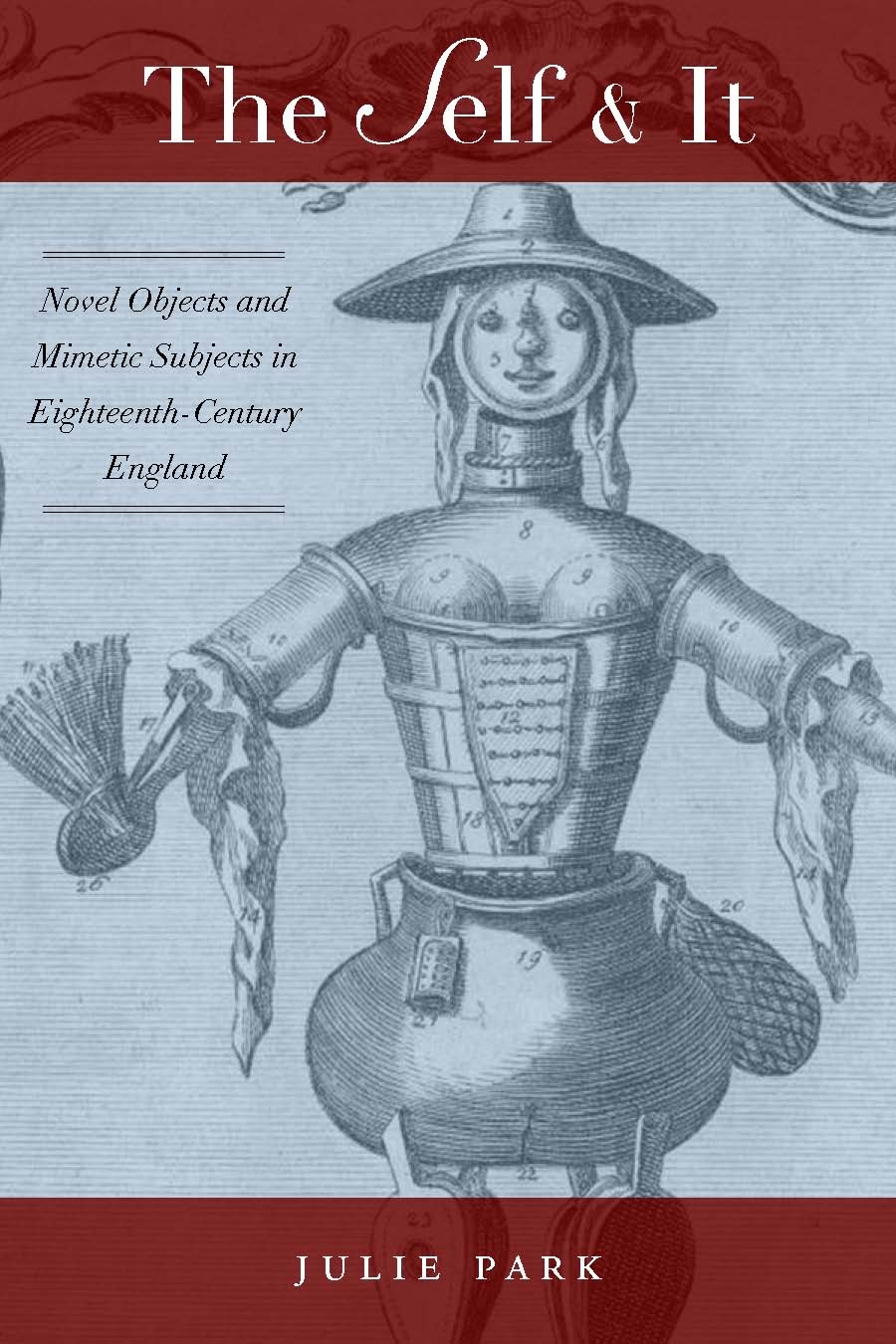

An Ahmanson-Getty Postdoctoral Fellowship at the UCLA Center for 17th- and 18th-Century Studies and Clark Library, as well as a Mellon Fellowship at the Huntington Library provided me with the time and funding to write this book. I am grateful to Helen Deutsch, Mary Terrall, Peter Reill, and Roy Ritchie for hosting a wonderful year in Southern California. Other sources of support for this book include grants and fellowships from the Faculty Committee on Research at Vassar College, the Mellon Centre for British Art, the Lewis Walpole Library, and the Folger Shakespeare Library. I am also indebted to the Woodrow Wilson Foundation for awarding me the Charlotte Newcombe Dissertation Fellowship, the National Maritime Museum for the Caird Short-Term Research Fellowship, and the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies for the Aubrey Williams Research Travel Grant. Caroline Goodfellow, doll curator of the Bethnal Green Museum of Childhood; Jill Shefrin, independent scholar; and the marvelous Joan Sussler, former curator of the Lewis Walpole Library, introduced me to many of the material artifacts that appear in this book. I am indebted to Caroline Goodfellow for telling me about twentieth-century half-dolls and to Joan Sussler for introducing me to the work of the Darlys and prints of women with big hair from the 1770s. Brian Parker of the Lewis Walpole Library showed me Moll Handy, the print that appears on the book cover. Without these specialists, I would never have been able to enter the world of wonderful things and images housed in their collections.

My family has shown me their support and constancy in ways I could not have predicted would mean so much to me. Mom, Dad, Michael, and Jane form my original tribe, and I am thrilled to welcome Young-Jae and Min-Jae Park, and Vera and Stella Kim as its new members. Animal love also cries out for acknowledgment. Orpheus and Whiskey have filled my days with warmth and character. Their late companions, brave Oscar and lovely Cleo have left regret over their leaving, but sweet memories, too. This book is dedicated to my mother and father, Won Joo and Nae Hong Park, who have marveled at my patience, as much as I have at theirs.

Notes

INTRODUCTION

Bernard Mandeville, A Search into the Nature of Society, in The Fable of the Bees , vol. 1, ed. F. B. Kaye (1714; Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 1988), 355. See also vol. 2, ed. F. B. Kaye (1729; Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 1988). Further references to these works are by title, volume number, and page number in the main text.

John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding , ed. Peter H. Nidditch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), book 2, chap. 27, sec. 17.

Alexander Pope, A Critical Edition of the Major Works , ed. Pat Rogers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

Ronald Paulson indicates that Hogarth based this illustration on Jonathan Swifts satire of the clothes worshippers in Tale of a Tub . I discuss Swifts sartorists in Chapter 1. See Ronald Paulson, Putting Out the Fire in Her Imperial Majestys Apartment: Opposition Politics, Anticlericalism, and Aesthetics, ELH 63, no. 1 (Spring 1996): 11 n .