Contents

Guide

Page List

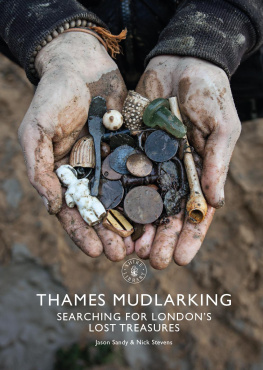

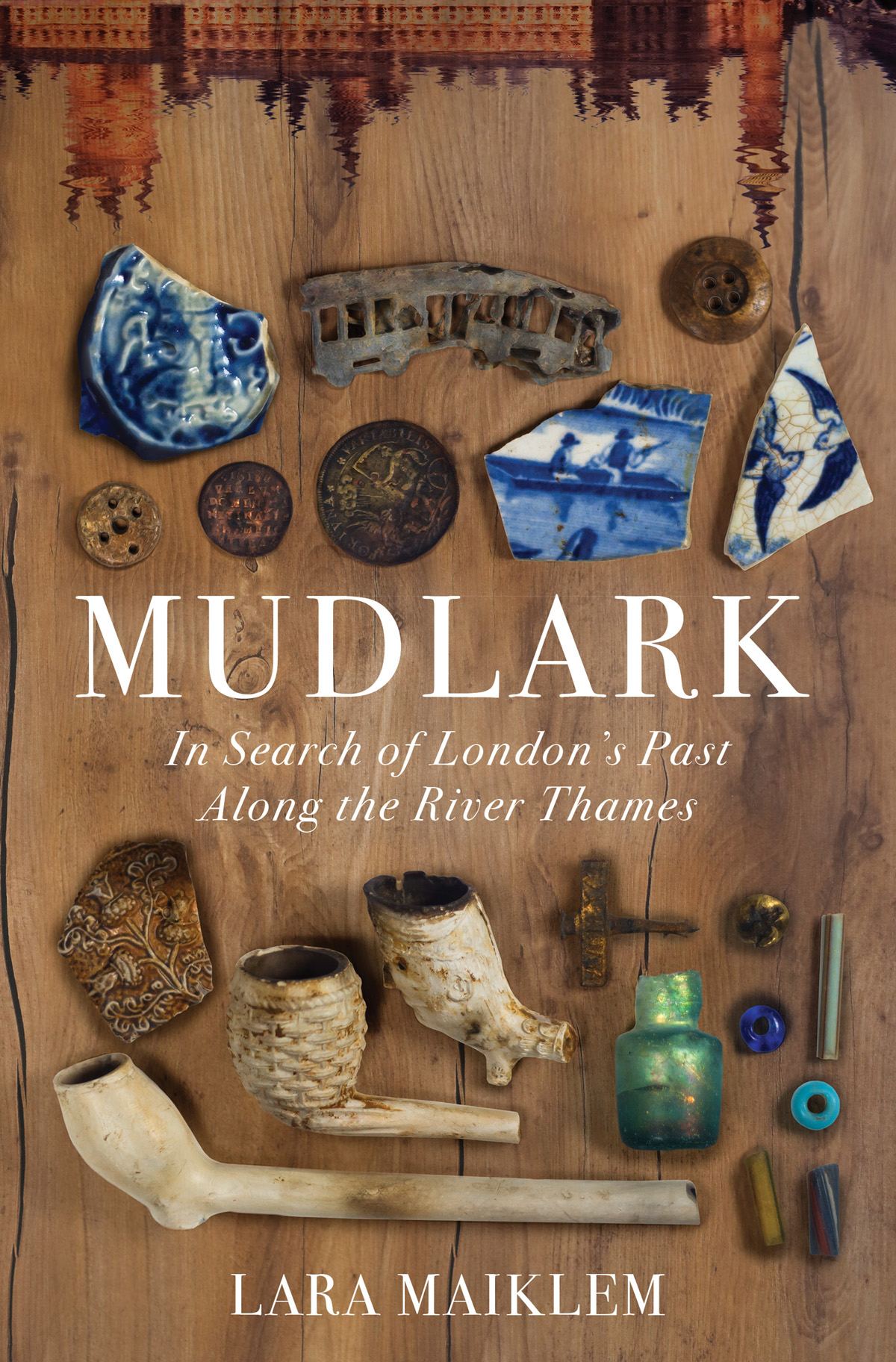

MUDLARK

In Search of Londons Past Along the River Thames

LARA MAIKLEM

For my mother

an old woman with a nut-cracker nose and chin, which almost dipped into the filthy slush into which she peered, and dirty flesh as well as a scrap or two of dirty linen showing through the slashes of her burst gown, over which, for warmths sake, she wore a tippet of ragged sack-cloth She slinks off to her lair, followed by an imp bearing a rusty crumpled colander, piled with its find. Its sex is indistinguishable. It has long mud-hued hair hanging down in a mat over its shoulders. Through the hair one gets a glimpse of a never-washed little face, whose only sign of intelligence is an occasional glance of wicked knowingness.

Richard Rowe, A Pair of Mudlarks,

Life in the London Streets (1881)

CONTENTS

Mudlark /mAdla;k / n. & V. L18. [F. MUD n.1 + LARK n.1] A n. + 1 A hog. slang. L18 E20. 2 A person who scavenges for usable debris in the mud of a river or harbour. Also, a street urchin; joc. a messy person, esp. a child. colloq. L18. 3 A magpie-lark. Austral. L19. 4 = MUDDER. slang. E20. B. v.i. Carry on the occupation of a mudlark. Also, play in mud. M19.

Mudlarker n. + MUDLARK n. 2 E19.

New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

on Historical Principles (1993)

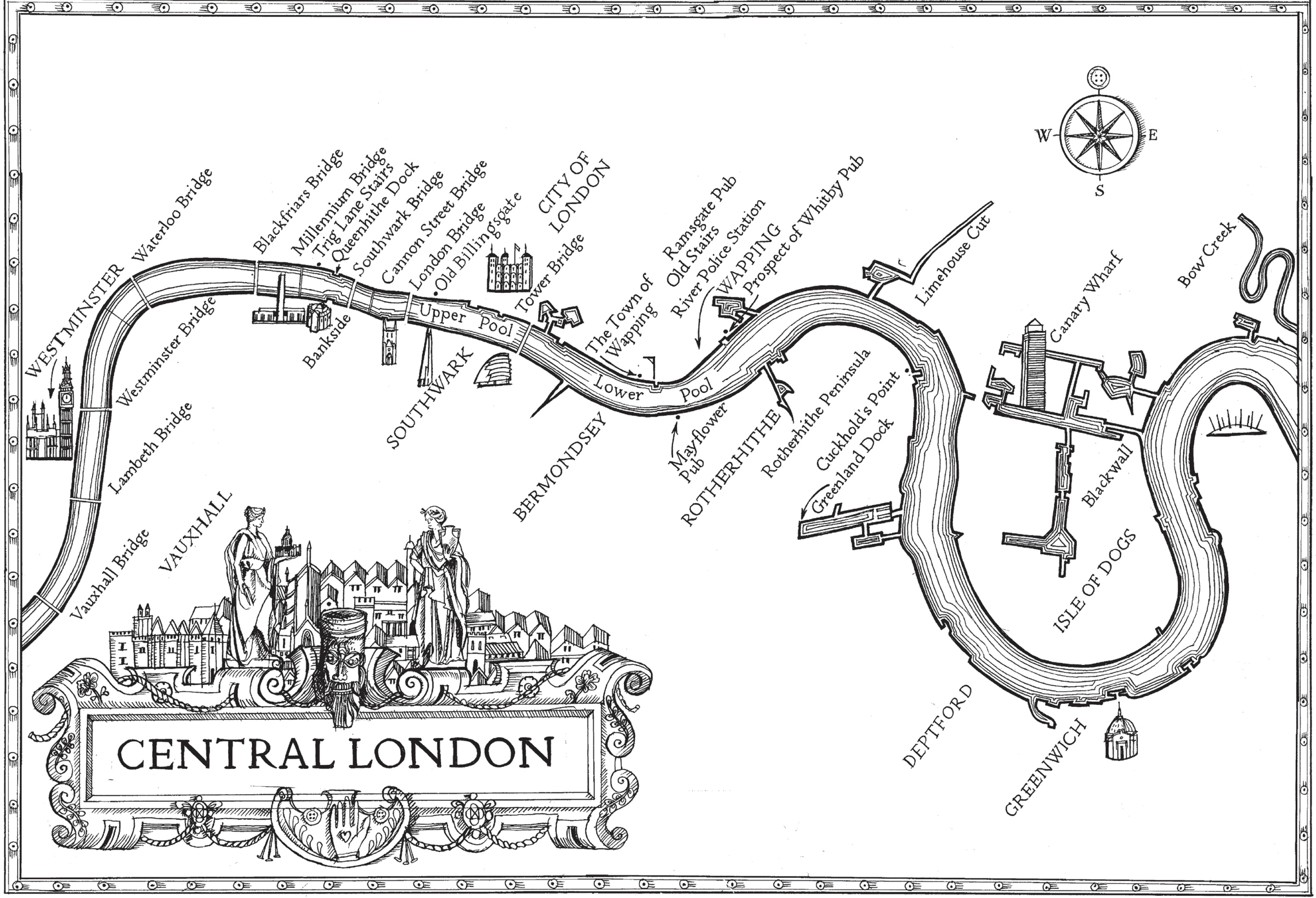

I t is hot and airless on the 7.42 from Greenwich to Cannon Street. I am squeezed between strangers, straining to avoid the feel of unknown bodies. No one makes eye contact and no one speaks. There is an unwritten rule of silence on the early-morning London commute and barely a murmur can be heard, just the rustle of newspapers and the high-pitched squeal of the rails as we lurch and sway towards the city.

I know every inch of this route. For nearly twenty years it has been taking me to the centre of London, for work, to meetings, to see friends and to visit the river in search of treasure. I know when to hold on tight, where the tracks jolt the train to one side, how long the gaps are between stops and when the driver will start to slow down for the next station. For years I have watched old graffiti fade and new graffiti appear. For six months now I have been watching a sports sock, discarded and stuck to the tracks, turn from white to tattered dirty brown.

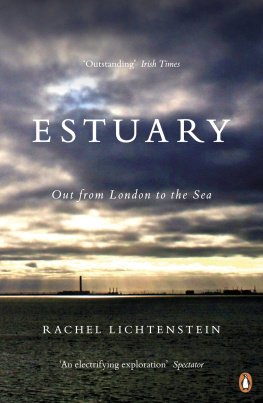

This journey will take me seventeen minutes and I am impatient. I check my watch again and work back three hours from todays predicted low tide. The river will be at its lowest at 10.23 a.m. My timing is perfect. I twitch and shift from foot to foot as the train pulls out of London Bridge station, willing it to speed up: I am almost there. We trundle over a railway viaduct, past Southwark Cathedral with its dappled flint dressing and Gothic spires, and through the centre of Borough Market. I look out over its glazed roof and try to spot the cast-iron pineapples balanced above one of the entrances. Then the sky opens up and I am above the river on Cannon Street Bridge, water flowing towards me from the west and away from me to the east. I scan the river on both sides, peering through the bodies, over newspapers and around rucksacks to check the tide. A patch of slime-covered rubble is just beginning to show through. It is close to the river wall, but the tide is falling. By the time I get down there the river will have dropped even further and enough of the foreshore will be exposed for me to begin my search.

It amazes me how many people dont realise the river in central London is tidal. I hear them comment on it as they pause at the river wall above me while I am mudlarking below. Even friends who have lived in the city for years are oblivious to the high and low tides that chase each other around the clock, inching forwards every twenty-four hours, one tide gradually creeping through the day while the other takes the night shift. They have no idea that the height between low and high water at London Bridge varies from fifteen to twenty-two feet or that it takes six hours for the water to come upriver and six and a half for it to flow back out to sea.

I am obsessed with the incessant rise and fall of the water. For years my spare time has been controlled by the rivers ebb and flow, and the consequent covering and uncovering of the foreshore. I know where the river allows me access early and where I can stay for the longest time before I am gently, but firmly, shooed away. I have learned to read the water and catch it as it turns, to recognise the almost imperceptible moment when it stops flowing seawards and the currents churn together briefly as the balance tips and the river is once more pulled inland, the anticipation of the receding water replaced by a sense of loss, like saying goodbye to an old friend after a long-awaited visit.

Tide tables commit the rivers movements to paper, predict its future and record its past. I use these complex lines of numbers, dates, times and water heights to fill my diary, temptations to weave my life around, but it is the river that decides when I can search it, and tides have no respect for sleep or commitments. I have carefully arranged meetings and appointments according to the tides, and conspired to meet friends near the river so that I can steal down to the foreshore before the water comes in and after its flowed out. Ive kept people waiting, bringing a trail of mud and apologies in my wake; missed the start of many films and even left some early to catch the last few inches of foreshore. I have lied, cajoled and manipulated to get time by the river. It comes knocking at all hours and I obey, forcing myself out of a warm bed, pulling on layers of clothes and padding quietly down the stairs, trying not to wake the sleeping house.

When I first started looking at tide tables, they confused me. Im not a natural mathematician and numbers just bewilder me, so a page filled with lines and columns of them sent me into a flat spin. But Ive been studying them for so long now that theyve become second nature. A quick glance and I can see which tides are good and when its worth visiting the river. The most important thing is to choose the correct tide table for the stretch you are planning to visit. There can be a difference of around five hours between low tide at Richmond and low tide at Southend, since the tide falls earlier in the Estuary than it does at the tidal head. Even the length of the low tide varies depending on where you are. While the rise and fall of tides in the open sea are of almost equal duration, twenty-five bends in the tidal Thames and the dragging effect of the riverbed and its banks shorten the rivers flood tide and lengthen its ebb tide. This means that the river stays at low tide for longer at Hammersmith than it does in the Estuary, which in theory equates to more mudlarking time the higher up the river you go, but even then, depending on the weather and the slope of the foreshore, the river can still catch you out.

I never look at the high-water levels, but I know that a good low tide of 0.5 metres and below will expose a decent amount of foraging space, so I scan the tide tables for these and circle them with a red pen. Spring tides mark the highest and lowest tides of the month. The name comes from the idea of the tide springing forth and not, as some mistakenly think, the time of year when they occur. There are two spring tides every month, during full and new moons, when the earth, sun and moon are in alignment and the gravitational pull on the oceans is greater, but the very best spring tides are after the equinoxes in March and September when they can fall into negative figures. They are known as negative tides because they fall below the zero mark, which is set by the average level of low tide at a specific place. A few years ago there was a run of freak low tides that were lower than most mudlarks could remember. Those were the best tides Ive ever seen. They revealed stretches of the foreshore that hadnt been mudlarked for over a decade and uncovered countless treasures.