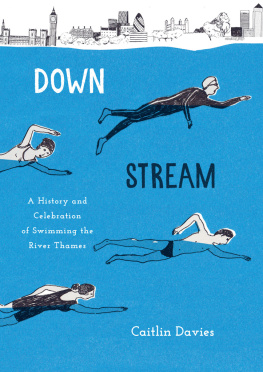

Downstream

First published in Great Britain

2015 by Aurum Press Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

Islington

London N1 9PF

www.aurumpress.co.uk

Copyright Caitlin Davies 2015

Caitlin Davies has asserted her moral right to be identified as the Author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Aurum Press Ltd.

Anne Jessel:

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material quoted in this book. If application is made in writing to the publisher, any omissions will be included in future editions.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78131 119 6

eBook ISBN 978 1 78131 488 3

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

2015 2017 2019 2018 2016

Typeset in Minion Pro by SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, Essex

eBook conversion by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

To all Thames swimmers, past, present and future...

Contents

For they were young and the Thames was old,

And this is the tale that the River told

Rudyard Kipling, The Rivers Tale, 1911

I m standing at the edge of a marshy meadow in Gloucestershire, cold water seeping into my wellington boots. In front of me, under an ancient ash tree, is a squat monument that looks like a tombstone, inscribed with the words: THE CONSERVATORS OF THE RIVER THAMES 18571974. THIS STONE WAS PLACED HERE TO MARK THE SOURCE OF THE RIVER THAMES. A wooden sign shows the direction of the Thames Path, which follows the river for most of its length, while the sign below reads Thames Barrier London 184 miles. Its early February and there have been flood warnings all along the path, following heavy snow, a thaw and general downpours. Normally this spot is bone dry, but today I could almost swim in it.

Beneath my boots is a clear pool of water, with blades of grass and smooth pale stones. A handful of bubbles rise to the surface and for a moment I wonder if there are fish in here, but this is water straight out of the Cotswolds earth, where a spring becomes a pool and then a stream. This is where, in theory, it all begins, this trickle of water that forms the longest river that is entirely in England, covering 215 miles from the heart of the countryside through its capital and out to the North Sea.

The River Thames has existed in one form or another for millions of years. It has been written and sung about, painted and mapped, portrayed as a place both majestic and dangerous, refreshing and polluted. It is father or grandfather Thames when noble or particularly chilly; it is mother Thames when tranquil and offering a watery embrace. People have drunk from it, washed and fished in it, and used it to dispose of every sort of waste. It has been a highway, a boundary and a food store, home to porpoises, whales, otters and sharks. An important trade and transport route since prehistoric times, it has carried passengers and goods from and to all over the world in boats of all shapes and sizes. We have rowed, sailed, canoed and punted along it; weve held regattas and aquatic carnivals, played water polo and skated over its frozen surface. But what of its swimmers? What of all those who have been drawn to its waters for enjoyment and to show off their skills, swims daring and reckless, theatrical and highly symbolic?

Before I started researching this book Id only ever swum once in the River Thames, some forty years ago on a warm summers evening near Taplow in Berkshire. I was ten years old and staying with a schoolfriend and I remember laughing as we tried to swim against the current. Id never considered its history as a place to swim, or stopped to wonder if my childhood splash made me part of a tradition. But it did, because this has been our bathing spot for centuries.

This is the story of Thames swimming as I travel from source to sea, visiting places with long traditions of river swimming, delving into town and city archives, interviewing modern-day swimmers, and looking for evidence, whether written, photographic or oral, of how we used to swim. I want to explore the character of the Thames and discover what it has meant, and still means, to the people who live by it and swim in it, to celebrate all those who have meandered along it and raced down it, who have submerged themselves for pleasure or for charity, who have performed spectacular divesfrom boats and bridges. What remains of how we once swam, what happened to the individuals and the clubs? Who has been documented and who has been forgotten?

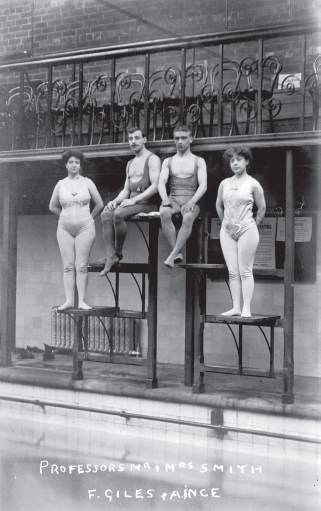

Victorian swimming professors taught people how to swim as well as giving public displays at indoor baths and in the Thames.

The Romans, who built the first bridge over the Thames, enjoyed military training swims, and for hundreds of years the river was the playground of royalty. Edward II swam as both Prince and King in the twelfth century; King Charles II was nearly assassinated while swimming near Battersea in the seventeenth century when the Thames was so clear and pure that noblemen swam in it all the time. Jonathan Swift took regular dips in the early 1700s; Lord Byron boasted of having swum three miles from Lambeth to London Bridge in 1807.

Soon the Thames was a major trading route for ships and, as a result, the river became the haunt of pirates and thieves. Yeteven as London became industrialised, as docks were built and warehouses lined its banks, people still swam. While history tells us that princes, kings, earls and poets swam in the Thames, as did the privileged public school boys of Westminster and Eton, the students and dons of Oxford University, what of the average person? This has always been our summer bathing spot. Seventeenth-century poet Robert Herrick sent his supremest kiss/To thee, my silver-footed Thamesis where in the summer sweeter evenings thousands bathe in thee.

But it was the fact people bathed naked that led to the first regulation of Thames swimming. In the mid-1800s indecency was seen as such a problem that male bathers were issued fines by local magistrates. What are the poor people to do? asked one letter writer to The Times, but to use the great highway of the Thames, when there were no baths in which to swim. But then the 1846 Baths and Washhouses Act allowed the building of indoor pools, swimming became popularised and it wasnt long before societies and clubs were formed. Soon the pupils of the National Swimming Society were racing in the Thames, despite the fact that sewage pollution was so severe it would result in cholera outbreaks.

Originally races were held for a bet and a dare. In 1791 three men apparently swam from Westminster Bridge to London Bridge for an eight-guinea wager. The winner was carried to a pub to celebrate, where he drank so much gin he expired. Then races for men became far more organised; in 1840 the aquatic jockeys raced twice across the Thames near Battersea, naked. The one-mile amateur championships began in 1869, from Putney to Hammersmith, while in 1877 the Lords and Commons race, the long-distance amateur championships of Great Britain, went from Putney to Westminster. Endurance swimmers also used it as their training ground, including Captain Matthew Webb, the first man to swim across the Channel successfully and unaided in 1875 and whose feat would transform the world of swimming.