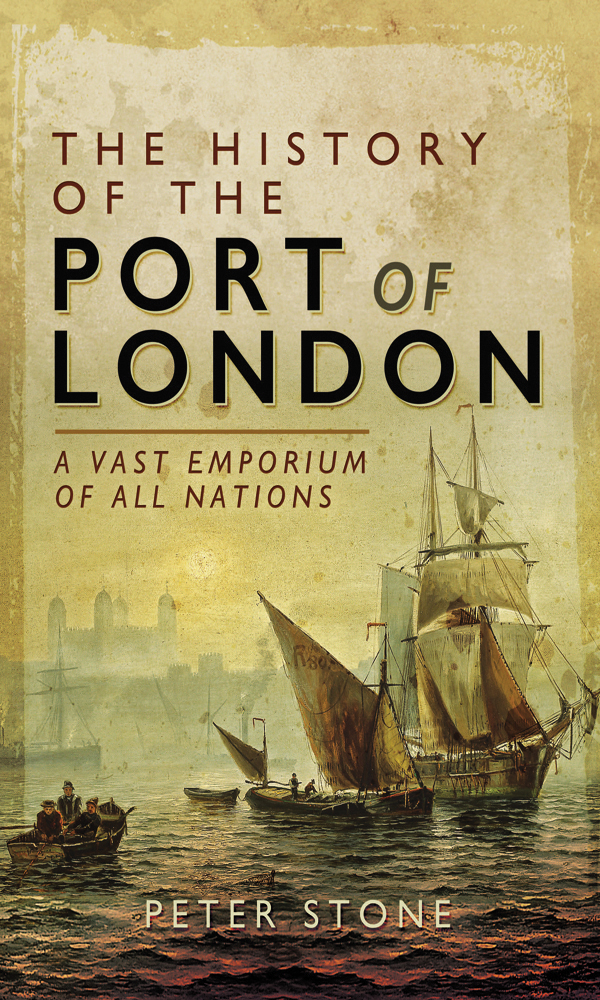

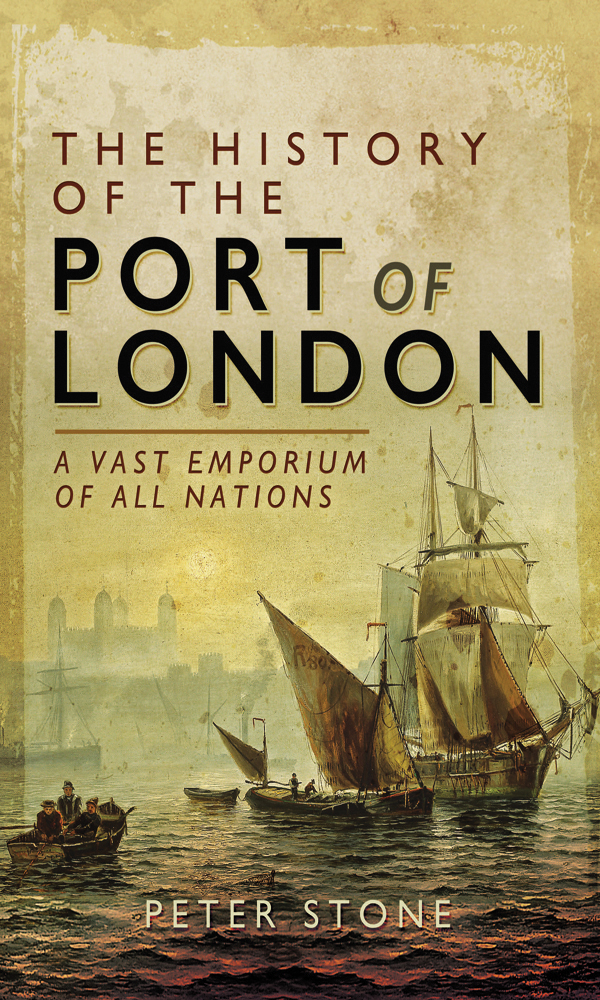

The History of the Port of London

The History of the Port of London

A Vast Emporium of Nations

Peter Stone

Maps created by Nick Buxey

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Peter Stone 2017

Some parts of this book first appeared on the website

www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 47386 037 7

eISBN 978 1 47386 039 1

Mobi ISBN 978 147386 038 4

The right of Peter Stone to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

W ith special thanks to Olwen Maynard and Ursula Jeffries who have done sterling work in reading through drafts of this book and challenging my facts, grammar and spelling. Mike Paterson of London Historians, Roger Williams (author of Londons Lost Global Giant amongst other books), Stephen Freeth (archivist at the Vintners Company and formerly Keeper of Manuscripts at the Guildhall Library), Geoff Marshall (author of Londons Docklands An Illustrated Guide ) and Chris Ellmers (President of the Docklands History Group, author of several books on the Port of London and a founder of the Museum of London Docklands) all read through and commented on certain chapters. Without these people this book would have contained numerous bloopers that have since been eradicated. Thanks also to Kate Bohdanowicz, whose idea it was that I should write a book and who introduced me to the publisher. During the course of researching, my knowledge of the Port of London has been greatly enhanced by the many talks I have attended at the Museum of Docklands, organized by the Docklands History Group. Chris Ellmers and Edward Sargent of the DHG have been particularly helpful. Numerous members of the aforementioned London Historians group have also encouraged me and spurred me on. Others who have contributed in their own way include Martin Garside and Samantha Broome at the Port of London Authority, who provided much useful information; Perry Glading, COO of the Port of Tilbury, who kindly answered my many questions with enthusiasm and obvious expertise, and his assistant Joanne Stroud for making arrangements and sourcing materials; and the helpful staff at: the British Library; the Guildhall Library; Tower Hamlets Local History Library at Bancroft Road, Mile End; the Museum of London; and the Peoples History Museum, Manchester.

Finally, I salute the many authors and historians who have gone before and thus provided me with invaluable source-material. Without their efforts my volume would not have been possible. You will find their work listed in the bibliography at the end of the book.

The quotation from Flora Tristans Promenades dans Londres was kindly translated from French to English by Ursula Jeffries.

The quotation from Julius Caesar was kindly translated from the Latin by Leonardo de Arrizabalaga y Prado.

The quotation by Gustav Milne is taken from his book The Port of Medieval London and used with his permission.

The quotation by L. Granade is taken from the book The Singularities of London, 1578 , published by the London Topographical Society and used with the permission of the Society.

The quotation from Edward Sargent is taken from a talk he gave to the Docklands History Group, April 2016, and used with his permission.

All photographs and illustrations within the book are from the authors collection unless otherwise stated.

I sincerely apologise if I have unknowingly used any material without permission that is still within copyright.

This book is dedicated to my father, William Doug Stone, who unwittingly first introduced me to Londons docks, but passed away during the writing and is greatly missed. Also to my mother, Lily Stone, whose stories about growing up in wartime Stepney and Limehouse have inspired me to study Londons history, particularly the East End.

Preface

T he ancient London Bridge had stood on the same foundations since the end of the thirteenth century. After years of patching, making-do and deliberation, in July 1823 an Act of Parliament was finally passed for the City of London Corporation to replace it with a completely new crossing. On 15 June 1825 a ceremony was held in which John Garratt, Lord Mayor of London, laid the foundation stone for the new structure. In the stones cavity was carved an inscription that explained why the old bridge was being replaced. It was a time of universal peace, claimed the texts author, with the British Empire flourishing in glory, wealth, population, and domestic union. The Metropolis has been daily advancing in elegance and splendour. Echoing an eighth century description of London, it described the city as a vast emporium of all nations.

The nations wealth was being driven by a major empire and trading network that spanned the globe, while at home the Industrial Revolution created new methods of production. London was the Empires economic capital, the workshop of the world as it was described during the Great Exhibition of 1851, and at the heart of the vast emporium was the Port of London. Raw materials and foodstuffs arrived and manufactured goods were dispatched. The docks and wharves were also a hub an entrept through which cargoes passed on their journey from one part of the world to another. London became a rare example of being both a port and capital city.

Since Roman times the citys raison dtre had been the Thames. The town had been founded where Roman troops could most easily cross the river, but the small settlement soon grew into a trading port where seagoing ships would arrive from Gaul and beyond. The port became so busy and congested that in the early eighteenth century the writer Daniel Defoe claimed to have counted two thousand sailing ships at one time. For centuries, goods were loaded and unloaded at riverside wharves, but twenty years before Lord Mayor Garratt was laying the foundation stone, a series of major new docks had been created on the east side of the metropolis, the first step to expanding the port into what would become the largest in the world.

London became a trading place and finance centre because it was a port. And because it was all of those things it was, until the Second World War, Britains greatest manufacturing base. Without the port, London could never have developed into the great city it became. In the latter part of the nineteenth century the writer Walter Thornbury gave the opinion: In no single spot of London, not even at the Bank, could so vivid an impression of the vast wealth of England be obtained as at the Docks.

Next page