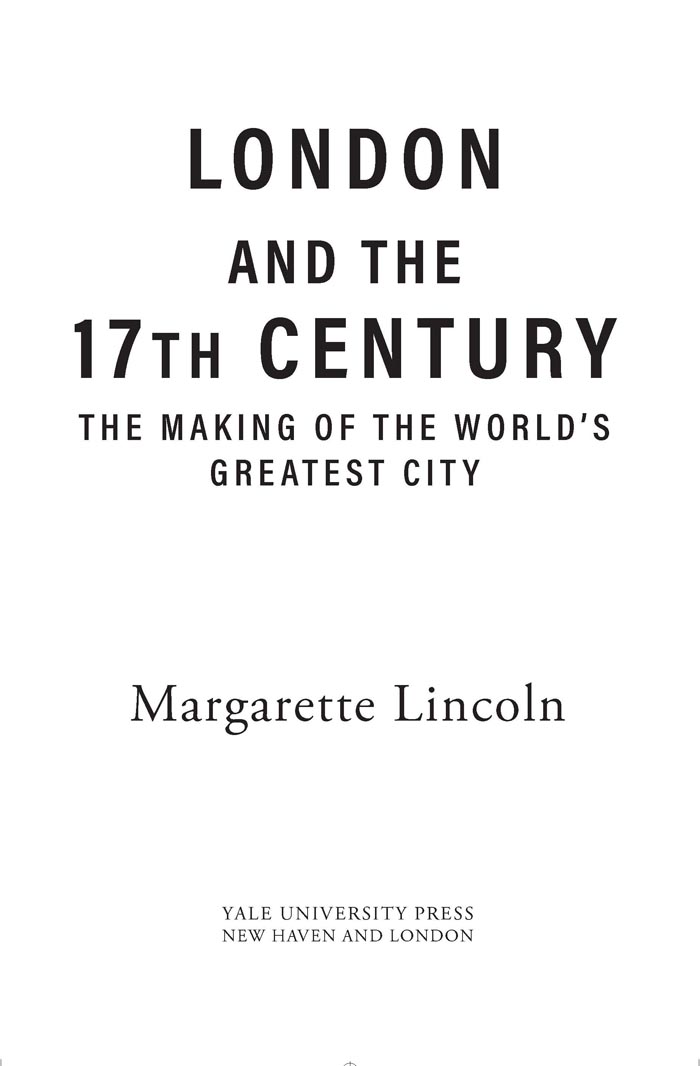

LONDON AND THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

Copyright 2021 Margarette Lincoln

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Garamond Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020946723

ISBN 978-0-300-24878-4

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Annie and Sophie

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

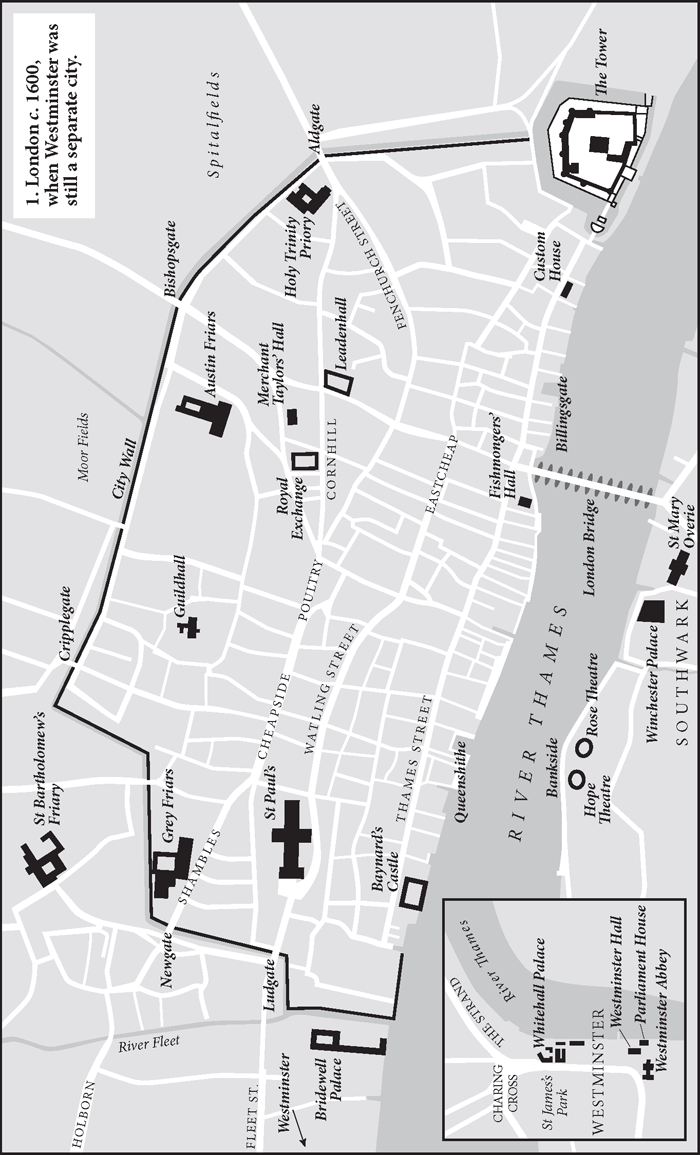

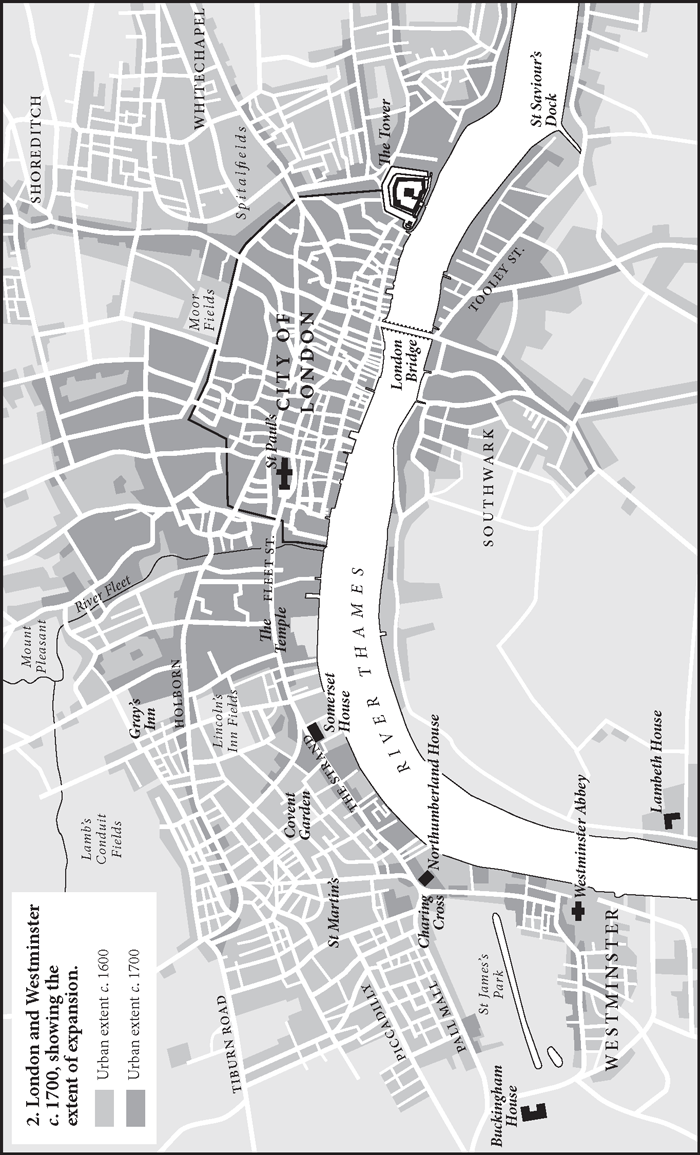

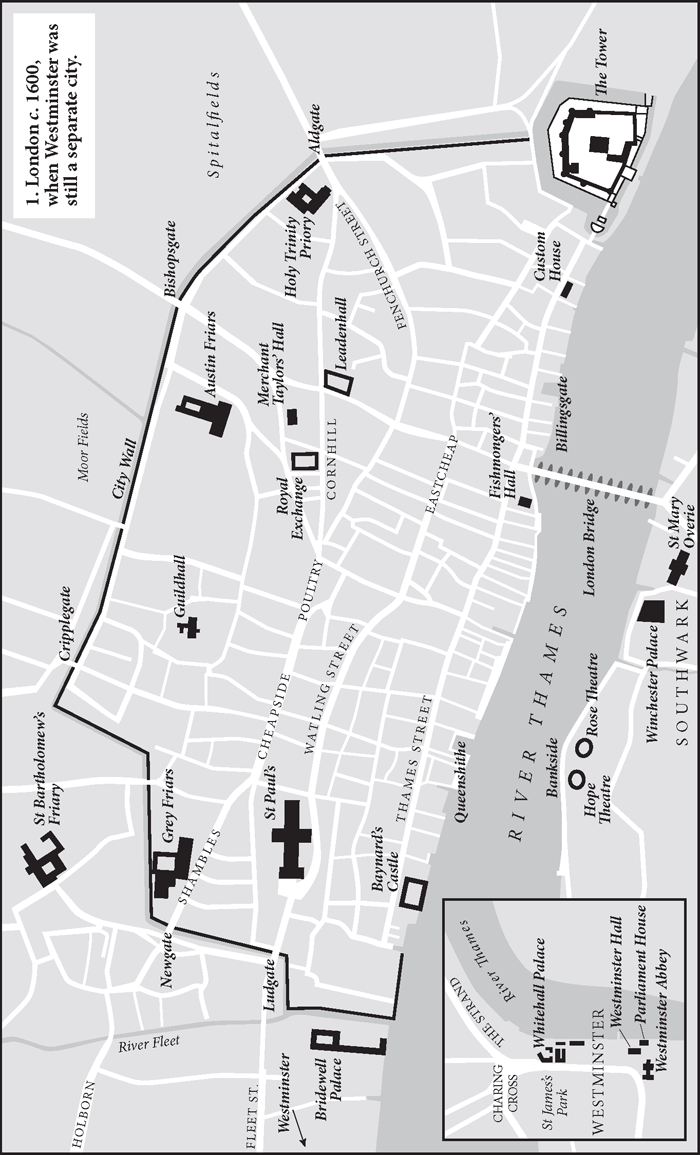

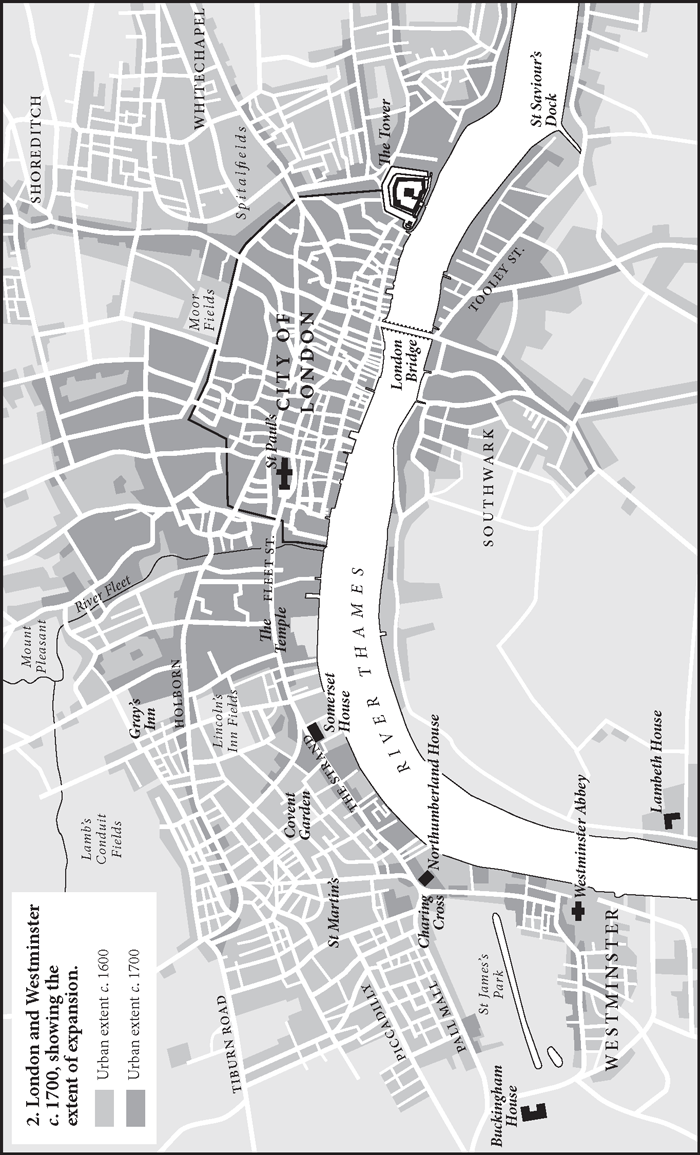

MAPS

PLATES

.

.

NOTE ON CONVENTIONS

During the period covered by this book, England, Wales and Ireland followed the older Julian Calendar, which was ten days behind the new-style Gregorian Calendar that most European countries used. All dates in the text are given in the Old Style but, as in modern usage, the New Year has been taken to commence on 1 January. Although 25 March (Lady Day) remained the official start of the year, 1 January had been called New Years Day from at least the thirteenth century.

In quotations, the original spelling, punctuation and capitalization have been retained throughout. And in this period, u and v were often used interchangeably.

The symbols s. d. denote the pre-decimal currency in Britain of pounds, shillings and pence. Under this system there were four farthings in a penny, twelve pennies in a shilling and twenty shillings in a pound.

The Bank of England calculates that goods and services costing 1 in 1600 would cost 1 9s. 8d. in 1700, and 224.60 in 2019: https://www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare.

Before decimalization, Britain used imperial units of weight. There were 16 ounces (ozs) to the pound (lb), 14 pounds to a stone, 2 stones to a quarter and 4 quarters to a hundredweight.

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The seventeenth century was a remarkable period in Londons history, which saw the emergence of the capital as a modern city. This book seeks to chart that progress, steering a path between matters of high politics and the thoughts and deeds of ordinary people. It includes merchants and artisans, not just royalty and military figures, and traces the untold stories of everyday Londoners. It surveys the entire century, helping to put major events and reversals into perspective. It delivers a broad political, economic and religious context for everyday life in the capital, unusually placing the history of London as a port alongside its social and political history. And it explores the civic use of public spectacle, rituals and pageants throughout the century. Overall, the book offers fresh insights into a fascinating age. The seventeenth century was not simply a disastrous epoch of domestic ills, civil strife and defeat at the hands of the Dutch. Londons dynamic population showed tremendous energy and resilience in adversity. An extended history of London in this period helps to explain how England could emerge from such a turbulent century poised to become a great maritime power. At a social and cultural level this book also shows how masculine and feminine identities in these years were in part forged through the making of a modern, cosmopolitan city and how, increasingly, London gathered significance as an imagined landscape. The distinctive developments that took place in Stuart London continue to influence our impressions of the city today.

In writing this book I have received help and encouragement from many friends and colleagues. I owe a special debt to my agent, Maggie Hanbury, who first suggested that I explore the subject, and to my editor, Julian Loose at Yale University Press, who has provided expert advice throughout. I am grateful to Yales anonymous specialists who reviewed both the book proposal and the manuscript; they gave helpful advice and saved me from several factual errors. Thanks are also due to the hard-working team at Yale who oversaw the production of the book, particularly to Rachael Lonsdale, Marika Lysandrou, Lucy Buchan, Katie Urquhart, and Tree Abraham who created the jacket design. I was fortunate to have Richard Mason as my copy-editor, and the text has benefited immensely from his helpful suggestions. I would also like to thank proofreader Robert Sargant and cartographer Martin Brown.

I would also like to thank my former colleague Liza Verity, who shared useful source material, Jenny Moseley who arranged access to the archives of the Sir John Cass Foundation, and Roger Knight and Timothy Walker for a valuable preliminary discussion about this fascinating century and the relevant archives. Goldsmiths, University of London, offered a stimulating intellectual environment, and my particular thanks go to Vivienne Richmond and John Price.

I owe a great practical debt to expert staff in various libraries, archives and museums: the British Library, the British Museum, the Courtauld Institute of Arts libraries, the Guildhall Library, Lambeth Palace Library, the London Metropolitan Archives, The National Archives, Kew, and the Caird Library at Royal Museums Greenwich. Special thanks to Melanie Johnson of the British Library for checking references when Covid-19 restrictions were in place. My understanding of daily life in seventeenth-century London owes much to museum collections as well as to archives and libraries.

Most of all I am indebted to my husband for generously taking time from his own work to read versions of all the chapters and for listening with patient enthusiasm to innumerable stories from the period. I may just have convinced him that the key to understanding London, and possibly Britain itself, is to be found in the seventeenth century.

OH WHAT AN EARTH-QUAKE IS THE ALTERATION OF A STATE!

Londoners opening their shutters at first light on Monday 28 April 1603 found the day promised to be dry and clear. Before the smoke from early-laid fires had spiralled up many chimneys, crowds were hurrying west, beyond the City and down the Strand to Whitehall, hoping for a good view of Queen Elizabeths funeral procession to Westminster. The City of London and its neighbouring City of Westminster were already linked by a ribbon of development either side of the route. Most of these buildings were palaces or noble mansions with fine gardens behind, owned by courtiers and the elite. Here the air smelled sweeter and there was far less noise. The public road went through the palace complex at Whitehall, where the queen had been lying in state for three weeks. Pedestrians could make out shadowy movement behind upper windows as people took up the best positions to watch the show.

The mood was not particularly sombre. In the past decade, Elizabeth had lost much of her popularity as poverty and crime in England increased with disastrous harvests and a costly war with Spain. Some were glad to see her go. Yet the queens officials had genuinely feared that her demise would cause violent disruption, even civil war. London had grown jittery during the queens last illness; many predicted that the succession would not be smooth. A watch was placed on the City, its gates were closely guarded, and lanterns were kept burning all night. In this crisis, the Privy Council took extreme precautions: vagabonds who might cause trouble were deported to Holland on the pretext of sending them to serve the Dutch, suspects were incarcerated, and the navy was ordered to keep a close watch on the Channel. There was more than one possible claimant to the throne and religious differences continued to plague the country. The queen herself had never named her successor for fear of inciting rebellion.

Next page