Contents

Guide

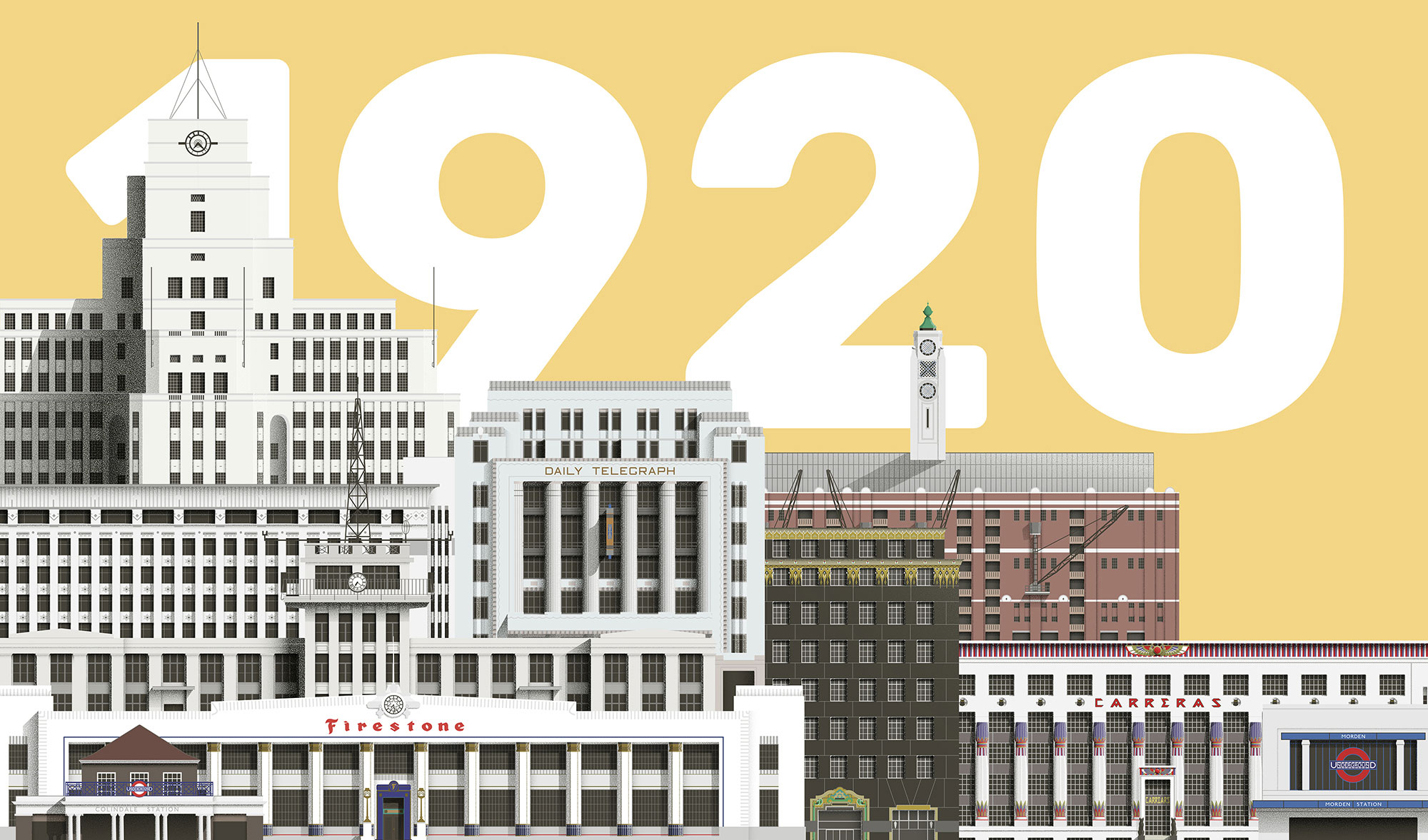

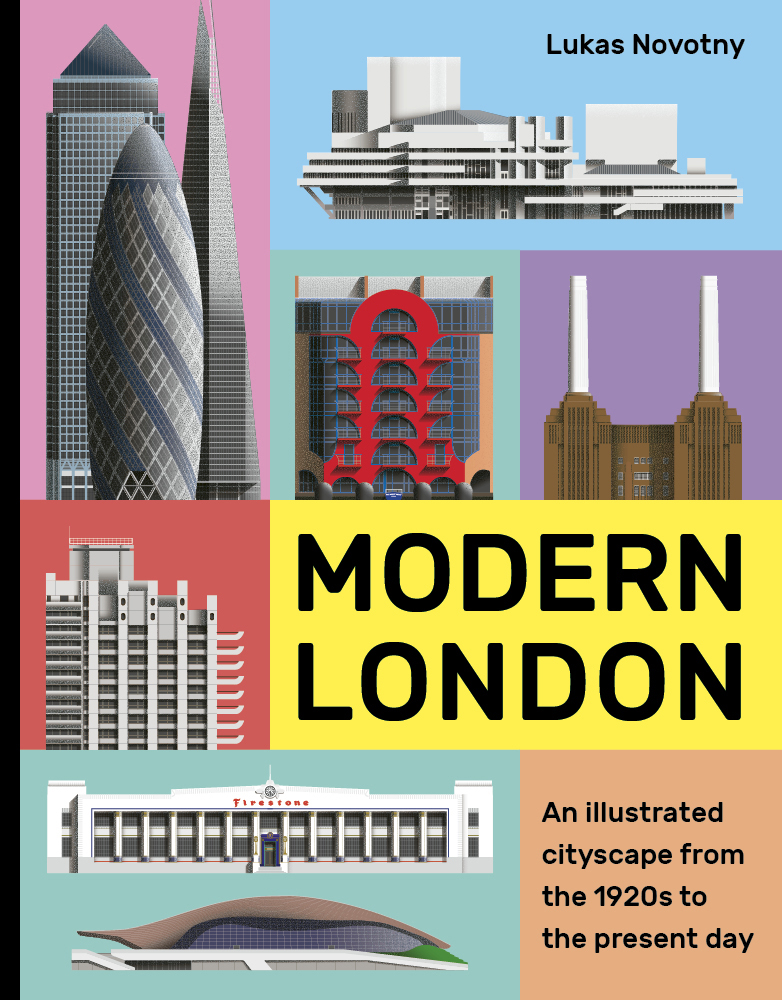

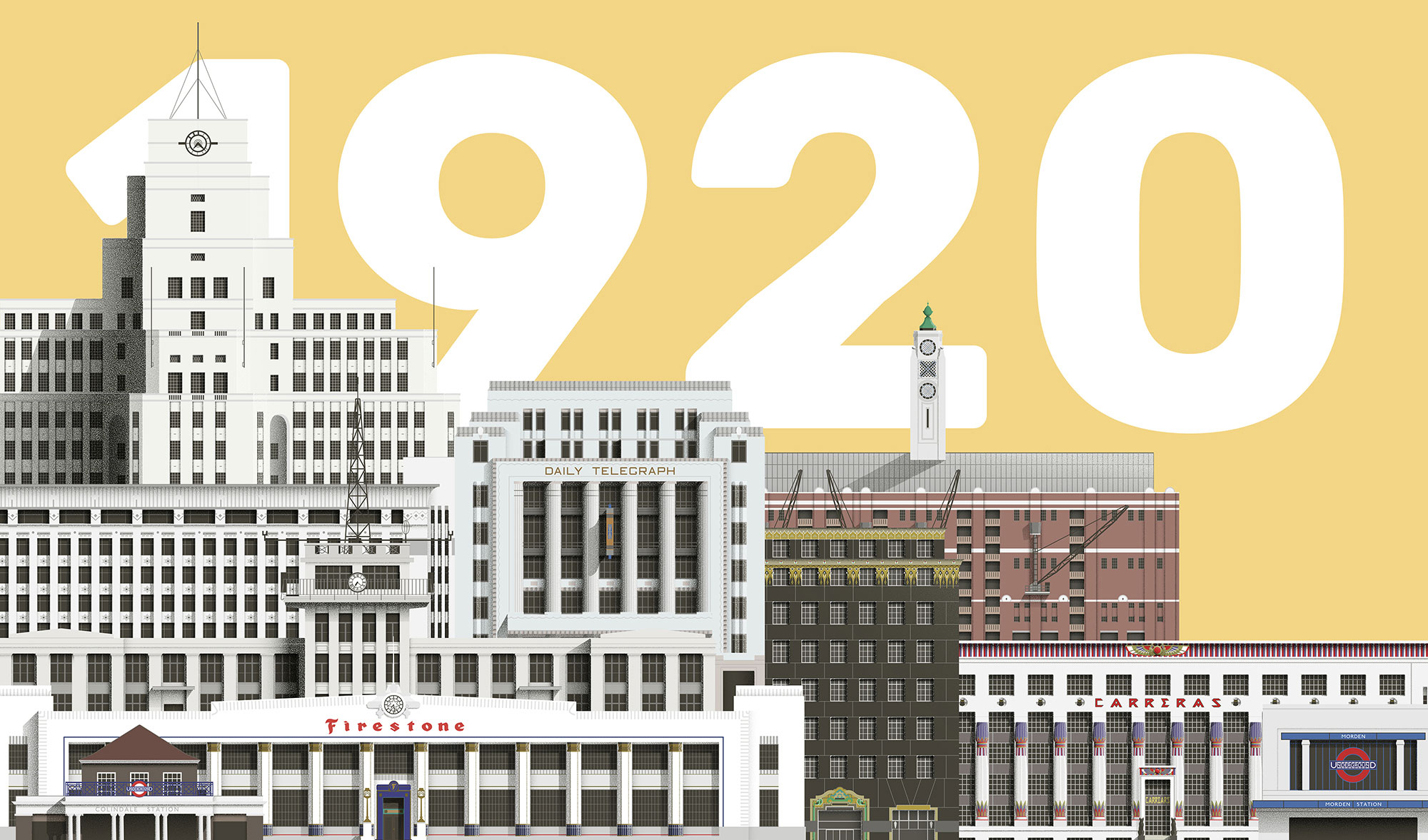

MODERN LONDON

An illustrated cityscape from the 1920s to the present day

Lukas Novotny

The Beginning

Modern London tells the story of how London, a seemingly untameable tangle of a city, became modern. Its an intriguing tale of struggle between the long-held and esteemed architectural traditions of the island nation and the inescapable influences of modern American and European design. Divided into decades, a century of evolution from the 1920s to the present day is explored through the illustration of dozens of notable buildings; an eclectic mix of popular landmarks, demolished masterpieces and forgotten oddities. Each are placed in their wider cultural context by technological and transport innovations of the time.

Unlike New York with its patchwork grid, and Paris with its long, tree-lined boulevards, London is not the result of a grand plan it was (and still is) shaped by invisible and often contradictory forces. The pace of change of the cityscape is ever increasing, and so its now more important than ever to understand how London came to look as it does today. Reading this book might not only help you understand the capitals history and present-day visage, but also give you clues as to its architectural future.

The shadows of enemy airships gliding ominously through Londons night sky may be a thing of the past. But at the dawn of the 1920s, the Great War which took 16 million lives and left the European continent devastated is just two years gone. Nevertheless, London, the largest city in the world at the time, has been left more or less unscathed, its economy in fact prospering from the development of arms factories and the rise of female employment. As war restrictions are lifted, the West End lights up with new night clubs and jazz bars. At the same time, big aristocratic mansions make way for grand new hotels hoping to attract the custom of wealthy Americans. A change is in the air.

In the 1920s, Londons large customer base, relatively cheap labour and docks linked by ship to cities around the world made it an ideal location for manufacturing. Emerging American companies soon set up shop, and aspiring British businesses looked up to these overseas corporations and their practices. Architecture soon became a method of advertisement. Confident and bold faades competed for attention and paid little mind to the opinions of critics.

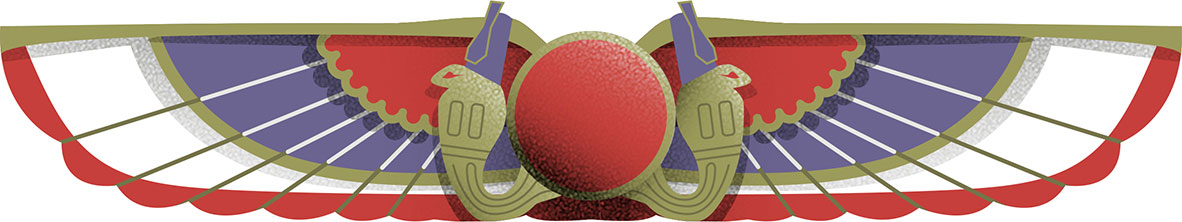

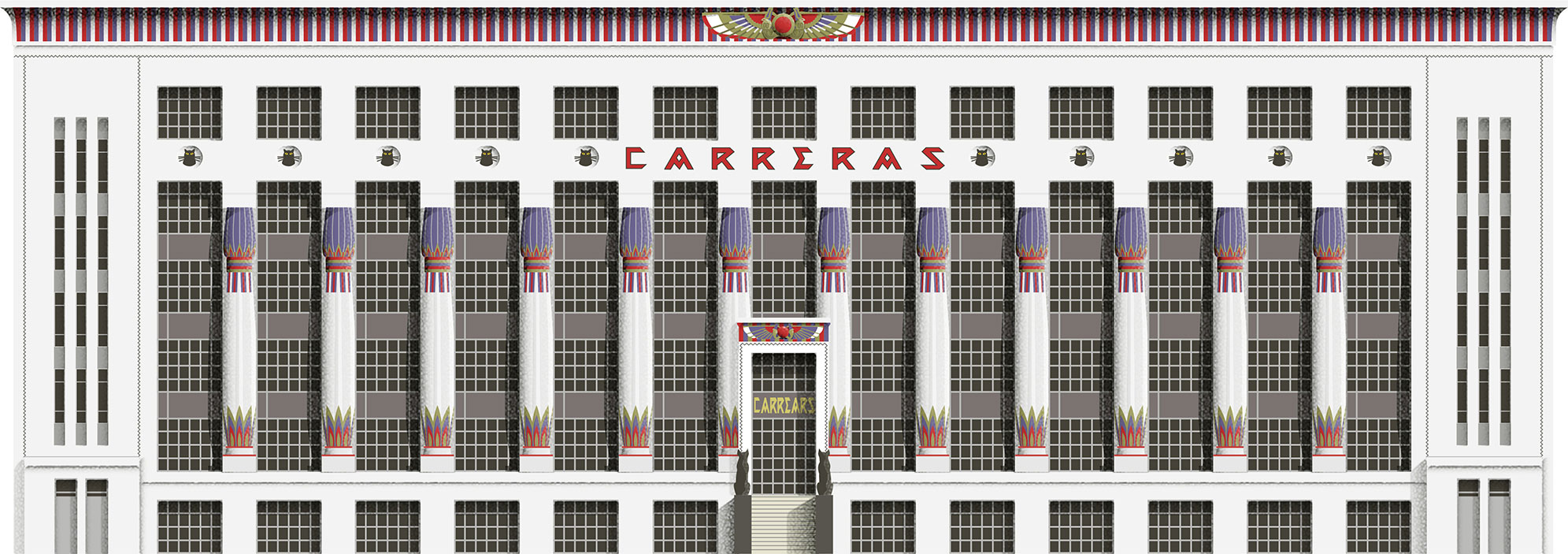

A perfect example of this is the Carreras Black Cat Cigarette Factory in Camden. Following the discovery of the intact tomb of Tutankhamun in 1923, the British public had become obsessed with ancient Egypt and everything to do with it; Egyptian motifs started to appear on new buildings across the capital.

Carreras Black Cat Cigarette Factory

M.E. & O.H. Collins with A.G. Porri

1928

1928  NW1 7AW

NW1 7AW

Carreras bosses liked the idea, and decided to take it one step further. The faade of their new factory would come to resemble an ancient Egyptian temple. Painted in bright colours, covered from head to toe with Egyptian dcor and guarded by two sculpted cat-gods, it certainly attracted the attention of the public. To ensure that nobody missed the trick, an extravagant opening day saw the streets around the factory transformed into an African desert scene. The pavements were buried in sand and processions of actors in Egyptian costumes streamed through the streets. They even staged a chariot race.

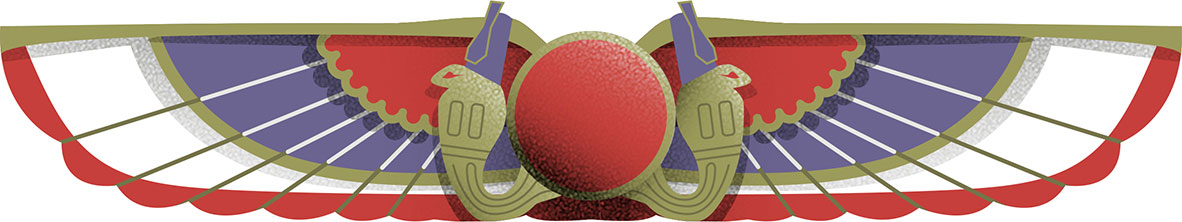

But just ten years later, when the threat of Nazi occupation loomed large, certain people worried that the winged sun motif adorning the faade too closely resembled the Nazi eagle, and it was swiftly covered up. In 1961, when the factory was converted into offices, the Egyptian style had long gone out of fashion and all the decoration was chiselled away. Even the round columns were boxed, to give the building a more modern appearance. In the 1990s, however, people came to appreciate the style once again. The building was renovated and most of the original decoration restored, although the winged sun motif didnt come back.

Among the numerous American corporations competing for space in the city was the Ohio-based Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. A factory was built on the Great West Road, which soon became a hotspot for overseas businesses. The Firestone Factory was designed by Wallis, Gilbert and Partners itself a partnership between an American construction company and an English architect. It was built with incredible speed from drawing board to finished building it took a mere twenty-one weeks. The faades composition and decoration was once again inspired by ancient Egypt, although it was far more restrained than that of the Carreras factory.

Firestone Factory

Wallis, Gilbert and Partners

1928

1928  1980

1980  TW7 5QD

TW7 5QD

In 1980, due to high wage costs, industrial unrest and high prices caused by the oil crisis, the factory workers were laid off and the land was sold to a developer. Both the local council and the Department of the Environment worked hard to get the building listed, but the developer Victor Matthews soon got wind of this and ordered its quick demolition. It was destroyed over the August bank holiday weekend, two days before the building was due to be listed and saved. The demolition was a nasty shock to many and it accelerated efforts to protect other industrial landmarks, such as the Hoover Building .

Police Box Mark 2

685 sturdy concrete boxes situated across London worked as a direct telephone connection to a police station. They first appeared in 1929 in a design by Gilbert Mackenzie Trench. The box gained international fame thanks to the Doctor Who television series, in which it featured as a time machine.

New office buildings of successful British corporations and banks rose up all around the financial district of London, commonly known as the City (note the capital c). The most modern was Adelaide House , designed by Scottish architects John J. Burnet and Thomas S. Tait. Both had travelled to the US before, with Tait working for a short time in New York City; their travels were to have a noticeable influence on the finished building. When it opened in 1925, it became the tallest and most modern office building in London. It was the first office block to have a steel frame, central ventilation and a telephone connection on every floor. There was even a fruit garden and an eighteen-hole mini golf course on the roof. The faade incorporates a mixture of American modernism and, of course, ancient Egyptian motifs.

1928

1928  NW1 7AW

NW1 7AW

1980

1980