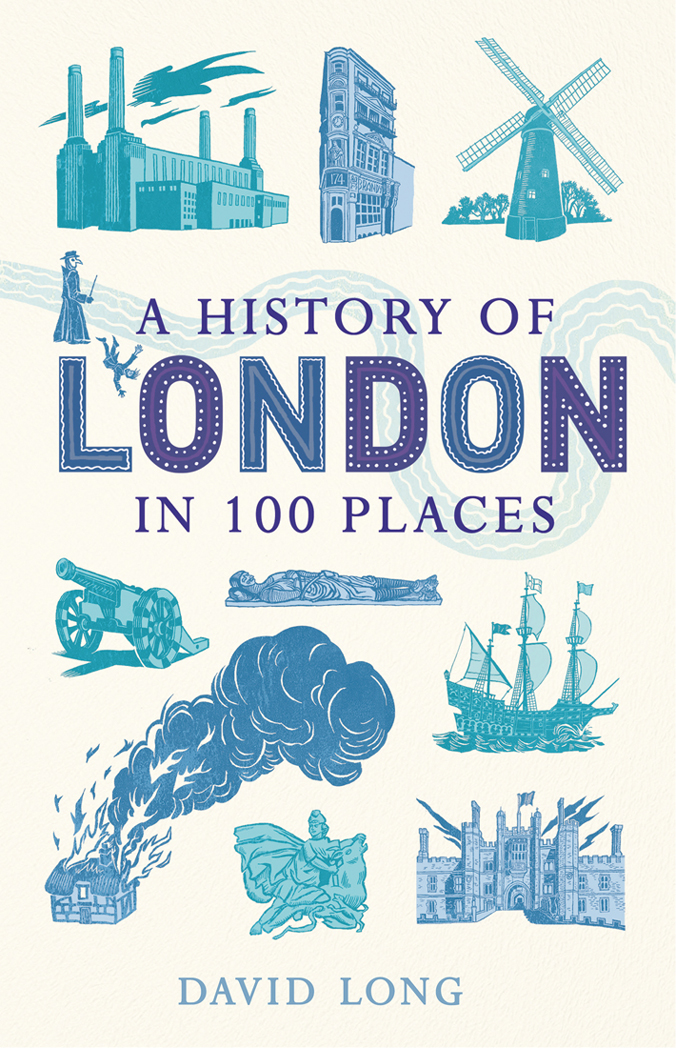

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Writer and journalist David Long has regularly appeared in The Times and the London Evening Standard , as well as on TV and radio. He has written a number of books on London, including Spectacular Vernacular , Tunnels Towers & Temples and the highly successful Little Book of London . He lives in Suffolk, England. Find him online at www.davidlong.info.

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications 2014

Copyright David Long 2014

The moral right of David Long to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-413-1

ISBN 978-1-78074-414-8 (eBook)

Text design, typesetting and eBook by Tetragon Publishing

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

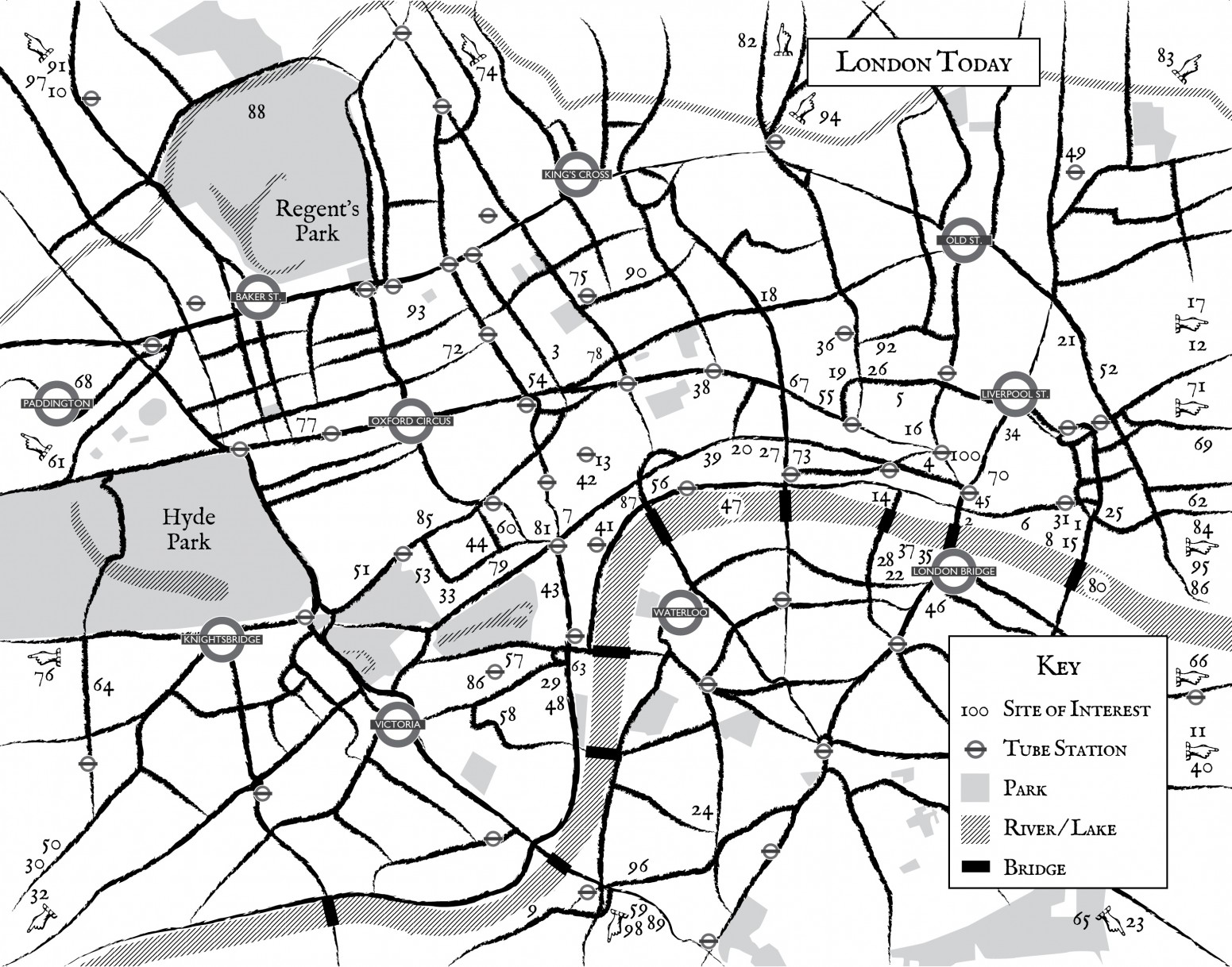

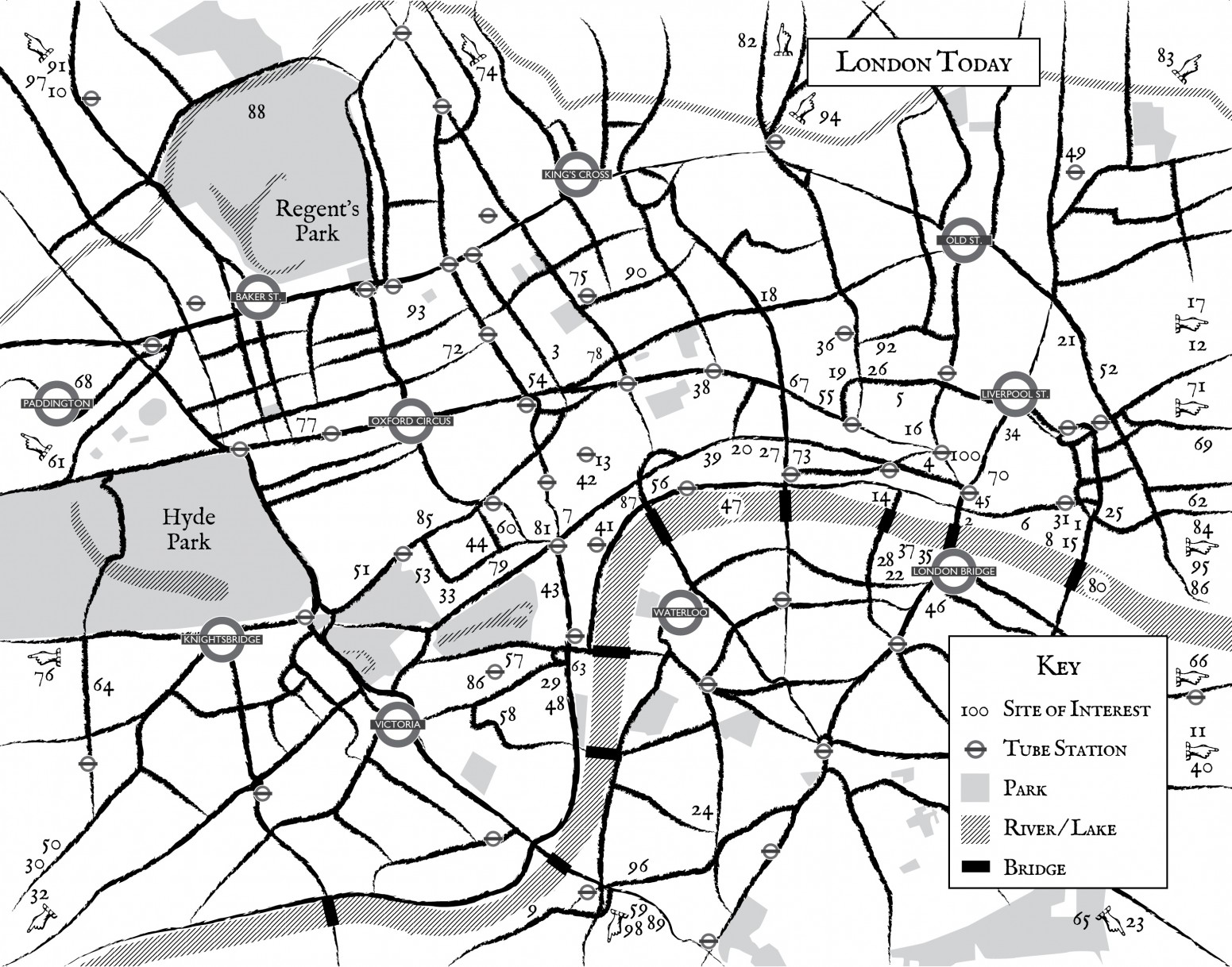

Contents

Introduction

A great world city shaped by invasion, occupation and immigration, by upheavals as diverse as the Great Fire, the Blitz and the Big Bang, London may no longer be the largest metropolis it lost the lead to New York a hundred years ago but after two thousand years its history and its cultural heritage are unmatched.

Walk the streets today and it is hard to ignore what went before. The city may reinvent itself on an almost perpetual basis, the skyline always pricked by cranes and skeletons of steel, but everywhere there are clues to Londons past.

Besides Roman walls, Saxon fish traps and Norman churches, there are medieval markets that are still trading today, surviving fragments of great monastic foundations, timber-framed houses that against all odds managed to withstand the flames of 1666, and elegant streets and squares from the earliest exercises in practical town planning. Best of all, the vast majority of them can be visited, often at no charge, and on such visits readers will find this book to be a useful companion.

It is true that very little is known of the time before the Romans arrived, that their first settlement was more or less destroyed by Boudicca and her Iceni warriors, and that many later iterations of London lie buried deep beneath huge new developments in and around the Square Mile. But across the capital fresh discoveries are still being made all the time and, while much of the past remains elusive, Londoners and visitors to their city are genuinely spoilt for choice when setting out to explore its long riotous history.

Some of the most evocative relics of past centuries are still to be found complete in all their splendour, classed as world-famous buildings; others are just foundations or the outline of a place or even, in the case of the great frost fairs, no more than contemporary accounts of what went on upon the frozen Thames. But from these remains emerges a picture of London that is as vibrant, as unique and as incredible as anything we see around the city today. Fast moving, always changing, and never standing still: it is a place we can relate to and that we can literally reach out and touch.

Chapter 1

Roman Londinium

There is frustratingly little to know of London before the coming of the Roman legions. Beyond a few random pottery shards and an Iron Age burial within what are now the precincts of the Tower of London, there is no conclusive evidence for any real settlement ahead of Julius Caesars arrival in 54 BC . The likelihood is that people were already scratching out a living of sorts somewhere along the wide, marshy valley of the Thames traces of a Bronze Age footpath have been found in Plumstead but no one can say with certainty where they might have lived, or how.

For the Romans, however, the river provided an obvious line of defence. In AD 43 soldiers of the second invasion force (in the reign of Claudius) ran a bridge from one side to the other, and it is around this that Londinium can be said to have developed. Both bridge and settlement were famously destroyed by Boudicca and an avenging Iceni army in AD 60. A thick layer of ash attests to this, more than ten feet below todays street level and writing only a few years later the Roman historian Tacitus confirms that at the time of its destruction the settlement had been thriving, a place filled with traders and a celebrated centre of commerce.

1. London Wall

Tower Hill, City of London, EC3

Militarily the early trading post had been of little importance, but following the carnage of Boudiccas ferocious onslaught Tacitus tells of literally thousands being massacred, hanged, burned and crucified a fortress was built in the north-western part of the city that we call Cripplegate. Later, in the third century, a defensive wall was thrown up around the remainder.

The finished wall in parts eight feet thick and as much as fifteen feet high enclosed an area of 330 acres, making London by far the largest city in Britain and the fifth largest in the part of the Roman Empire that lay to the north of the Alps. It was built largely of Kentish ragstone on foundations of flint and compacted clay, a hard grey limestone a rarity in south-east England that was to prove ideal for building strong and durable structures of this sort.

As well as some twenty-one bastions the wall incorporated six gateways Aldgate, Aldersgate, Bishopsgate, Cripplegate, Ludgate and Newgate that led out to the great Roman roads linking the city to the rest of England. In civil engineering terms, the whole structure was a major undertaking even by Roman standards, requiring an estimated thirteen thousand barge loads of stone to be brought up the River Medway and along the Thames from quarries located close to modern Maidstone.

Repaired, restored and where necessary improved, it was to enclose the city for more than one thousand five hundred years and the gates were only finally taken down in the mid-eighteenth century when they began to impede the traffic. Much of the stonework disappeared in the decades that followed their removal, but the surviving portions were nevertheless substantial enough that, following the Blitz, they were still among the tallest structures within that part of historic central London that today we know as the Square Mile.

Today various bits of the wall lie hidden in basements and cellars (for example, in the Old Bailey) but the most impressive fragments are those around the Barbican, on Noble Street and Coopers Row, and on Tower Hill. The upper courses are mostly medieval (at one point crenellations were added, although these have gone), but with their distinctive lines of red brick or tile bonding the Roman work is easy to identify. Still rising to a height of more than twelve feet, it represents perhaps the most evocative reminder of Londons earliest times.