Contents

Guide

To J. Roger Baker (193493).

He taught me more than he realised, and

would have enjoyed this a lot.

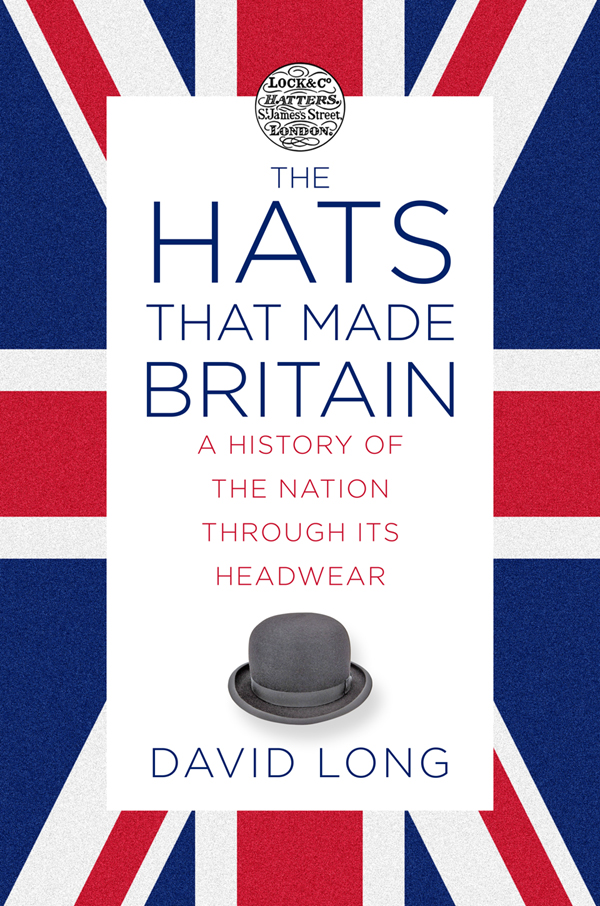

First published 2020

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

David Long, 2020

The right of David Long to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9588 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

It was a graded society and hats told you something. The elegant grey topper and the formal black silk set you apart from the bourgeois felt and the plebeian tweed, the official kepi and the schoolboys coloured cap

Philip Mason, The English Gentleman (1982)

From trilbies and top hats to boaters and bowlers, a hat reveals a lot about a persons character as well as their country, and much of Britains social history can be traced through the hats and headdresses of politicians and performers, as well as ordinary citizens.

The oldest known hats are the those found on small terracotta figures belonging to the ancient Indus River Civilisation. Examples discovered at archaeological sites such as Mohenjo-daro and Harappa date back between 3,500 and 5,700 years. At that time hats typically provided protection from the weather and occasionally weapons, although they soon came to play an important role in ceremonials before evolving yet again into decorative garments for the fashionable, the rich and the powerful.

By the Middle Ages there were civil and religious laws requiring hats to be worn, and in Victorian Britain they were such an important part of every self-respecting lady or gentlemans wardrobe that a person would no more leave home without a hat than a pair of trousers or a skirt. Poor people wore them too, of course, and for centuries hats were a visible symbol of a persons wealth, class and occupation, as much for the bowler-hatted city gent as for the lowly farmworker in his cloth cap.

Today they are worn far less often, although it is significant that Londons oldest shop is a hatter. Many of the best-loved fictional characters are still strongly associated with the hats they wore, from the Artful Dodger and his battered top hat to Chaplins famous bowler and even Del Boy from Only Fools and Horses with his trademark flat cap.

Hats are so much more important than mere theatrical props or fashion items, however. Many continue to play a role in some of the most deeply embedded national customs, both here and abroad. Graduates still tip mortarboards to their tutors, top hats are still required in the Royal Enclosure at Ascot, a coronation would be meaningless without a crown, and where would Haxey be without its famous medieval leather hood?

The old saying may no longer be true that if you want to get ahead, get a hat, and its hard to imagine a return to a world where literally everyone wore one. But hats still have a lot going in their favour. They dont just keep us warm, dry or shaded, and looking smart. Theres something terribly nice about tipping your hat to a friend or an acquaintance and theres still no finer way to hail a cab.

For a place most people in Britain rarely, if ever, visit, the historic City of London has bequeathed to these islands more than its fair share of common phrases and sayings. Several of these including at sixes and sevens, on tenterhooks, bakers dozen and if the cap fits, wear it have their origins within the Square Mile, these particular ones referring to the customs and traditions of the Livery, the Citys ancient craft guilds.

Another saying most of us are familiar with and understand is Ill keep it under my hat, meaning to keep something secret or hidden. However, few know its precise derivation, or that it refers to a particular and rather singular item of headgear.

The hat in question is that worn by the Citys official Sword-bearer, a ceremonial post closely associated with the Lord Mayor of London who is elected each year by the members of the aforementioned Livery companies. Its an ancient appointment, indeed so old that no one knows quite when the first man was appointed, nor indeed who he was.

The City is known to have possessed a ceremonial sword as long ago as 1373. In 1408 a man called John Credy was given a house rent-free in Cripplegate, in recognition of fourteen years good service as an Esquire to the Lord Mayor when his duties would have included carrying the sword before the mayor at official functions.

In the centuries when exactly this sort of privilege was granted by popes to sovereign heads of state, the right to have a sword carried before the Lord Mayor was a significant concession to the City and a clear demonstration of its wealth and status. The Citys wealth derived from its unique position as the chief trading port of the country (which in a sense it still is). Much of its status, however, depended on its relationship with the Crown. For hundreds of years the sovereign had most of the power but rarely enough money. Successive monarchs soon came to realise that in exchange for special rights and privileges the City could be relied upon to provide piles of it, more than enough to fund their palaces, their pageantry and their wars.

The sword was conceived as a tangible symbol of the privileges that flowed from this relationship, and it is significant that one of the five in the collection at Mansion House was a personal gift to the City from Elizabeth I. Her Majestys gift marked the opening of the first Royal Exchange, a vital centre for trade and commerce.

The prize of carrying it was duly given to a man well bred who knows how in all places, in that which unto such service pertains, to support the honour of his lord and the City. As such, it has always included various responsibilities connected to the running of Mansion House, but it is otherwise expressly ceremonial. Although the sword blade looks real enough, responsibility for protecting the Lord Mayors person remained with the Sergeant-at-Arms. (It still does today: his immense gold mace was originally a club-like implement, a weapon designed to keep the mob at bay while the Lord Mayor processed through the streets.)

While the heavy mace is a formidable piece of equipment, it is the Sword-bearer who cuts the more imposing figure. Although both officials wear similar black robes and lace collars, the Sword-bearer has the added advantage of a tall and magnificent hat which looks like beaver but is actually made of sable.