PENGUIN BOOKS

LONDON: A SOCIAL HISTORY

There are surprisingly few good general histories of London, New York or Paris concerned with where and how people worked, amused themselves, prayed, or raised families Roy Porter has a novelists eye for telling details about everyday life, and a scholars care for evidence. The book comes to life politically at the end, when he discusses the impact of the Thatcher years on Londons social fabric; Porter sees deeply engrained habits, survival strategies and street-wise pleasures which have marked the social history of Londoners rich and poor suddenly corroded within the space of a decade Richard Sennett, The Times Literary Supplement, Books of the Year

It should be read by every Londoner of whatever political persuasion; by every Briton who lives north of Watford or south of Croydon; and by anyone, anywhere, who is concerned about the current problems and future prospects of the worlds great conurbations. For cities, like nations, can only be understood in an historical perspective. It is that perspective which this book so brilliantly provides. In more senses than one, it is a capital history David Cannadine, Independent on Sunday

One of the virtues of this account is the range of contemporaneous quotation which Porter provides, giving full weight to that period when London was the wonder and the mystery of the world. But he is also very good on those details which mark the citys true and enduring identity Peter Ackroyd, The Times

A fascinating trawl through its colourful past Clare Colvin, Sunday Express

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Roy Porter is Professor in the Social History of Medicine at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London. Recent books include Mind Forgd Manacles: Madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency (Athlone, 1987); A Social History of Madness (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987); In Sickness and in Health: The British Experience 16501850 (Fourth Estate, 1988); Patients Progress (Polity, 1989), these last two co-authored with Dorothy Porter; Health for Sale: Quackery in England 16601850 (Manchester University Press); Doctor of Society: Thomas Beddoes and the Sick Trade in Late Enlightenment England (Routledge,1991); London: A Social History (Penguin, 1996); The History of Bethlem (Routledge, 1997), co-authored; The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (HarperCollins, 1997); and Gout: The Patrician Malady (Yale University Press, 1998), co-authored. He has also edited, with Jeremy Black, The Penguin Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century History.

Roy Porter

London

A SOCIAL HISTORY

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published by Hamish Hamilton 1994

Published in Penguin Books 1996

This edition published 2000

Copyright Roy Porter, 1994

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Acknowledgement is made to the following for permission to use extracts from: The Waste Land by T. S Eliot, reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber; Something in Linoleum by Paul Vaughan, reprinted by permission of Sinclair-Stevenson; The Girls of Slender Means by Muriel Spark, published by Penguin Books, reprinted by permission of David Higham Associates; Summoned by Bells and Thoughts on the Diary of a Nobody, from Collected Poems, and Betjemans London, edited by Pennie Denton, all by John Betjeman, reprinted by permission of John Murray (Publishers) Ltd.

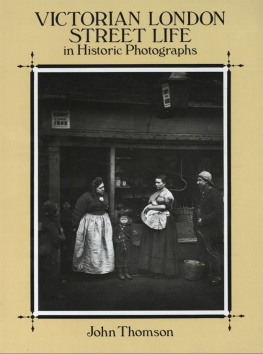

Acknowledgement is also made for permission to use the following illustrations: Fotomas Index, .

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 9780140105933

Contents

To my parents

List of Plates

List of Text Illustrations

When I grow rich,

Say the bells of Shoreditch

CHILDRENS SONG , Oranges and Lemons

From the bones of extinct monsters and the coins of Roman emperors in the cellars to the name of the shopman over the door, the whole story is fascinating and the material endless. Perhaps Cockneys are a prejudiced race, but certainly this inexhaustible richness seems to belong to London more than to any other great city.

VIRGINIA WOOLF , Review of E. V. Lucass London Revisited (1916)

I have often amused myself with thinking how different a place London is to different people. They, whose narrow minds are contracted to the consideration of some one particular pursuit, view it only through that medium. A politician thinks of it merely as the seat of government in its different departments; a grazier, as a vast market for cattle; a mercantile man, as a place where a prodigious deal of business is done upon Change; a dramatick enthusiast, as the grand scene of theatrical entertainments; a man of pleasure, as an assemblage of taverns, and the great emporium for ladies of easy virtue. But the intellectual man is struck with it, as comprehending the whole of human life in all its variety, the contemplation of which is inexhaustible.

JAMES BOSWELL , Fournal (1763)

Jerusalem Athens Alexandria

Vienna London

Unreal

T. S. ELIOT , The Waste Land(1922)

Preface

Maybe its because Im a Londoner, but when Peter Carson and Andrew Franklin invited me, more years ago than I can recall without shame, to write a social history of London, I leapt at the opportunity. I grew up in south London just after the war. Three miles from London Bridge, New Cross Gate was not exactly the Bethnal Green beloved of Young and Willmott, but it was a stable if shabby working-class community completely undiscovered by sociologists. In many ways, that past now seems another country: bomb-sites and prefabs abounded, pig-bins stood like pillboxes on street corners, the Co-op man came round with a horse and cart delivering the milk, everybody knew everybody. Some of the houses in Camplin Street still had gas lighting, as did my infant school; clanking trams are a vivid memory, and it was fun creeping to school through pea-soupers, a torch vainly held out in front. In those years of austerity ration-book coupons taught me my sums locals grumbled about how run-down and old-fashioned the area was, hemmed in by the railway sidings, canal and docks that had long provided secure employment but which imparted a grimy, dingy feel. The three-up, three-down council house that my parents shared with my grandparents and an uncle had an outside lavatory; a tin bath was hauled in once a week from the bottom of the garden, set down on the scullery floor, and filled from kettles and a wheezing Ascot gas water-heater. Domestic overcrowding was worsened but redeemed by the sanctity of the front room, used only at Christmas, though unlocked once a week so that the Rexine three-piece suite could be polished with Ronuk.

Next page