VICTORIAN LONDON

STREET LIFE

in Historic Photographs

John Thomson

Text by John Thomson and Adolphe Smith

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

Copyright

Copyright 1994 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1994, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London, in 12 monthly parts beginning in February 1877, under the title Street Life in London. The frontmatter has been rearranged, a new table of contents added, and a new Publishers Note written specially for the Dover edition. For reasons of space the illustrations, originally on unnumbered pages, have been integrated into the text with a consequent reordering of page numbers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thomson, J. (John), 1837-1921.

[Street life in London]

Victorian London street life in historic photographs / by John Thomson with text by John Thomson and Adolphe Smith.

p. cm.

Originally published: London : S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1877.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-28121-6 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-486-28121-3 (pbk.)

1. London (England)Social life and customs19th centuryPictorial works. I. Smith, Adolphe. II. Title.

DA683.T46 1994

942.12081dc20

94-11755

CIP

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

28121307

www.doverpublications.com

PUBLISHERS NOTE

BORN in Scotland in 1837, John Thomson was a pioneering documentary photographerone of a breed for whom arduous travel under extremely difficult conditions did little to dampen enthusiasm. Exploring and photographing China for ten years (1862-72), he published his photographs and texts of his journeys in The Antiquities of Cambodia (1867), Illustrations of China and Its People (1873-74; Dover reprint 0-486-26750-4) and The Straits of Malacca, Indo China and China (1877; illustrated by woodcuts).

Returning to London, Thomson turned his attention to the city, his Street Life in London (1877), reprinted here, frequently being credited as the first instance in which photographs were used as social documentation. He subsequently developed the art of at home portraits, was appointed photographer to Queen Victoria and was photographic adviser to the Royal Geographic Society. He died in 1921.

By the mid-nineteenth century, popular perception of the poor had changed. Previously viewed as morally defective, the poor were now regarded as the object of study and charity. Henry Mayhews monumental London Labour and the London Poor, published in 1851, had been illustrated by woodcuts based on photographs by Richard Beard. While Street Life in London is hardly as comprehensive a work as Mayhews, it has the virtue that its photographic reproductions not only show the subjects as they actually appeared but, by capturing the contemporary streetscape of London, also reveals them in their milieu.

While the book is most famous for these photographs, the text should not be ignored. Thomson wrote some (signed J. T), but most of it was written by Adolphe Smith (A. S.), a journalist who became an activist concerned with labor and the unions. The text is factual, but it is impossible not to detect the sympathy that both Smith and Thomson feel for their subjects who, more often than not, are threatened by deprivation and hunger. The costumes and backgrounds depicted in the photographs may seem picturesque to us today, but Thomsons subjects are caught in a seemingly unbreakable cycle of poverty that has reappeared in many urban areas to present its desperate challenge.

STREET LIFE

IN

LONDON.

BY J. THOMSON, F.R.G.S., AND ADOLPHE SMITH.

WITH PERMANENT PHOTOGRAPHIC ILLUSTRATIONS

TAKEN FROM LIFE EXPRESSLY FOR THIS PUBLICATION.

London:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET, LONDON.

[All rights reserved.]

[ORIGINAL TITLE PAGE]

PREFACE.

N presenting to the public the result of careful observations among the poor of London, we should perhaps proffer a few words of apology for reopening a subject which has already been amply and ably treated. We are fully aware that we are not the first on the field. London Labour and London Poor is still remembered by all who are interested in the condition of the humbler classes; but its facts and figures are necessarily ante-dated. In later times Mr. James Greenwood has created considerable sensation by his sketches of low life, but the subject is so vast and undergoes such rapid variations that it can never be exhausted ; nor, as our national wealth increases, can we be too frequently reminded of the poverty that nevertheless still exists in our midst.

N presenting to the public the result of careful observations among the poor of London, we should perhaps proffer a few words of apology for reopening a subject which has already been amply and ably treated. We are fully aware that we are not the first on the field. London Labour and London Poor is still remembered by all who are interested in the condition of the humbler classes; but its facts and figures are necessarily ante-dated. In later times Mr. James Greenwood has created considerable sensation by his sketches of low life, but the subject is so vast and undergoes such rapid variations that it can never be exhausted ; nor, as our national wealth increases, can we be too frequently reminded of the poverty that nevertheless still exists in our midst.

And now we also have sought to portray these harder phases of life, bringing to bear the precision of photography in illustration of our subject. The unquestionable accuracy of this testimony will enable us to present true types of the London Poor and shield us from the accusation of either underrating or exaggerating individual peculiarities of appearance.

We have selected our material in the highways and the byways, deeming that the familiar aspects of street life would be as welcome as those glimpses caught here and there, at the angle of some dark alley, or in some squalid corner beyond the beat of the ordinary wayfarer. It also often happens that little is known concerning the street characters who are the most frequently seen in our crowded thoroughfares. At the same time, we have visited, armed with note-book and camera, those back streets and courts where the struggle for life is none the less bitter and intense, because less observed. Here what may be termed more original studies have presented themselves, and will help to complete what we trust will prove a vivid account of the various means by which our unfortunate fellow-creatures endeavour to earn, beg, or steal their daily bread.

THE AUTHORS.

CONTENTS

VICTORIAN LONDON

STREET LIFE

in Historic Photographs

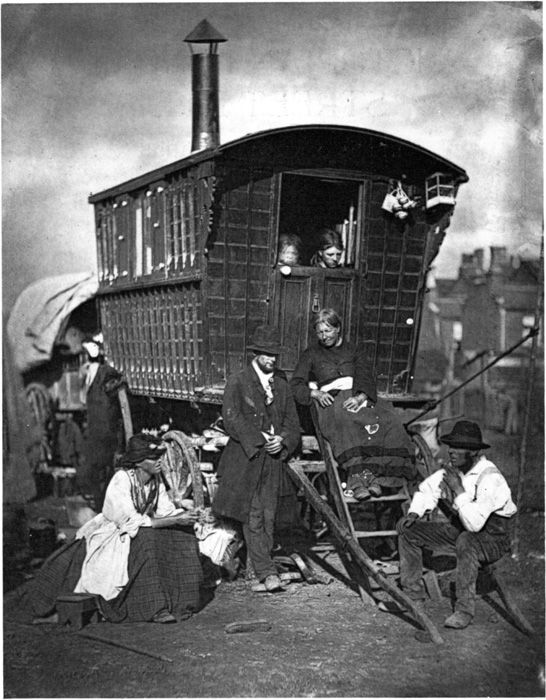

London Nomades

LONDON NOMADES.

I  N his savage state, whether inhabiting the marshes of Equatorial Africa, or the mountain ranges of Formosa, man is fain to wander, seeking his sustenance in the fruits of the earth or products of the chase. On the other hand, in the most civilized communities the wanderers become distributors of food and of industrial products to those who spend their days in the ceaseless toil of city life. Hence it is that in London there are a number of what may be termed, owing to their wandering, unsettled habits, nomadic tribes. These people, who neither follow a regular pursuit, nor have a permanent place of abode, form a section of urban and suburban street folks so divided and subdivided, and yet so mingled into one confused whole, as to render abortive any attempt at systematic classification. The wares, also, in which they deal are almost as diverse as the families to which the dealers belong. They are the people who would rather not be trammelled by the usages that regulate settled labour, or by the laws that bind together communities.

N his savage state, whether inhabiting the marshes of Equatorial Africa, or the mountain ranges of Formosa, man is fain to wander, seeking his sustenance in the fruits of the earth or products of the chase. On the other hand, in the most civilized communities the wanderers become distributors of food and of industrial products to those who spend their days in the ceaseless toil of city life. Hence it is that in London there are a number of what may be termed, owing to their wandering, unsettled habits, nomadic tribes. These people, who neither follow a regular pursuit, nor have a permanent place of abode, form a section of urban and suburban street folks so divided and subdivided, and yet so mingled into one confused whole, as to render abortive any attempt at systematic classification. The wares, also, in which they deal are almost as diverse as the families to which the dealers belong. They are the people who would rather not be trammelled by the usages that regulate settled labour, or by the laws that bind together communities.

N presenting to the public the result of careful observations among the poor of London, we should perhaps proffer a few words of apology for reopening a subject which has already been amply and ably treated. We are fully aware that we are not the first on the field. London Labour and London Poor is still remembered by all who are interested in the condition of the humbler classes; but its facts and figures are necessarily ante-dated. In later times Mr. James Greenwood has created considerable sensation by his sketches of low life, but the subject is so vast and undergoes such rapid variations that it can never be exhausted ; nor, as our national wealth increases, can we be too frequently reminded of the poverty that nevertheless still exists in our midst.

N presenting to the public the result of careful observations among the poor of London, we should perhaps proffer a few words of apology for reopening a subject which has already been amply and ably treated. We are fully aware that we are not the first on the field. London Labour and London Poor is still remembered by all who are interested in the condition of the humbler classes; but its facts and figures are necessarily ante-dated. In later times Mr. James Greenwood has created considerable sensation by his sketches of low life, but the subject is so vast and undergoes such rapid variations that it can never be exhausted ; nor, as our national wealth increases, can we be too frequently reminded of the poverty that nevertheless still exists in our midst.