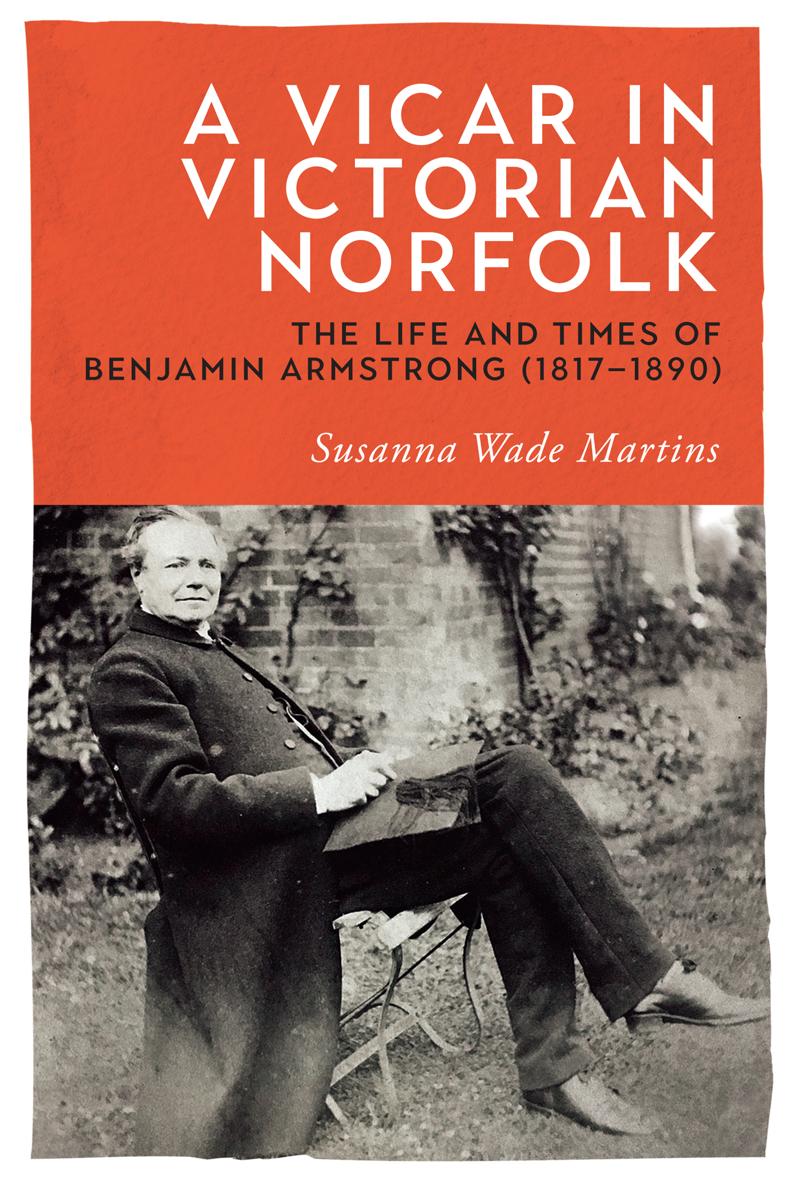

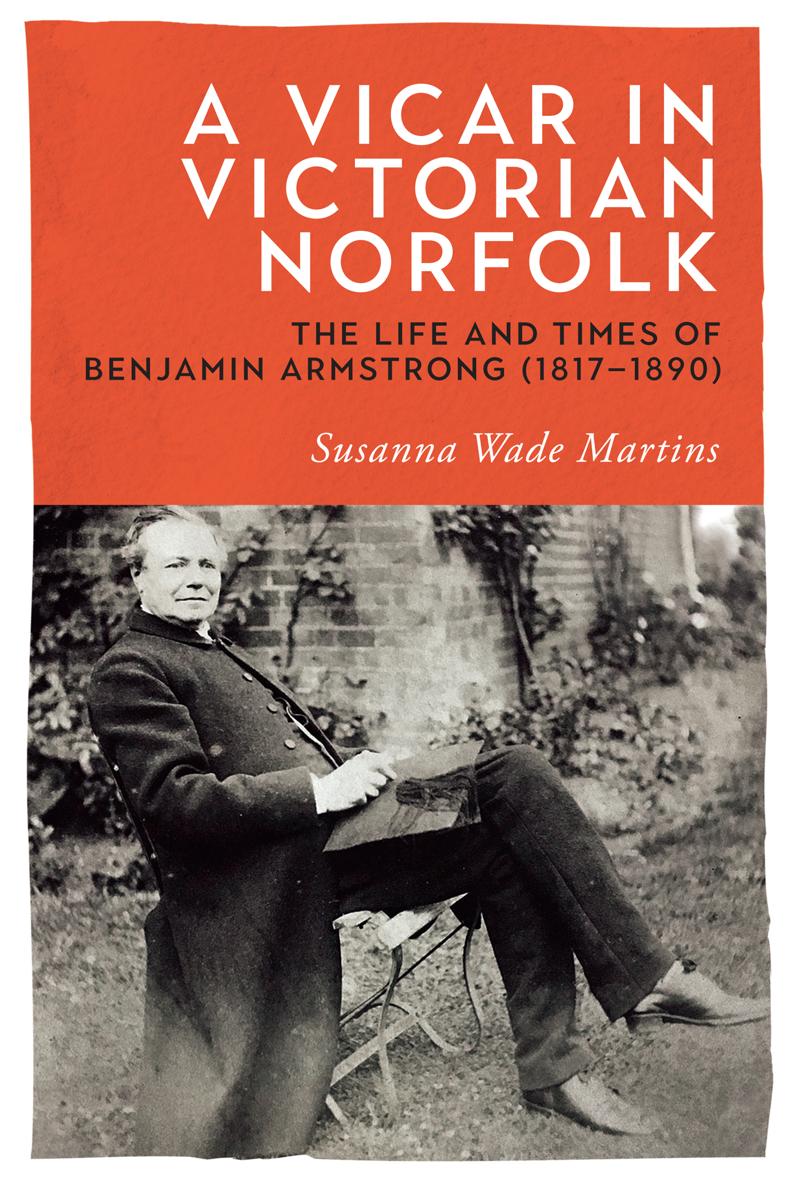

A Vicar in Victorian Norfolk

The Revd Benjamin Armstrong, for many years vicar of the market town of East Dereham, Norfolk, is best-known for what have been described as one of England's greatest clerical diaries, eleven volumes spanning his whole adult life, between 1850 and 1888. This first full biography puts his story into the context of the period in which he lived: a time of turmoil in the church, with its conflict between high and low forms of service, and theological arguments, stirred up not least by controversies over Darwin's theories of creation. It also vividly portrays rural life at a time of great change, when society became more fluid, railways allowed the economy to grow and develop, and the vote was extended. We see this through the eyes of Armstrong himself, a fine example of the then new-style Church of England clergy who lived in their parishes, took more services than their predecessors, supported their schools and showed a genuine concern for the well-being of their parishioners. By the time he retired, church life in Dereham had been transformed, with congregations typically of 1,000 at each of the Sunday services.

Armstrong also served on various Local Boards, as well as setting up the Literary Institute, the Rifle Volunteers and supporting musical and cultural events. He also had a full social life; his friends included prominent townspeople and the local clergy, gentry and aristocracy and there are incisive pen portraits of many of his associates and their eccentricities. These activities are set against the background of his family life, with its moments of tragedy and worry, including the death of a young child and the elopement of another.

Dr Susanna Wade Martins is an Honorary Research Fellow in the School of History at the University of East Anglia. Her previous publications include The East Anglian Countryside: Changing Landscapes 1870-1950 with Tom Williamson (2008), Coke of Norfolk, 1754-1842 (2009) and The Conservation Movement in Norfolk A History (2015).

Contents

Illustrations

Map of places mentioned in the text along with road and railway links used by Armstrong

The author and publishers are grateful to all the institutions and individuals listed for permission to reproduce the materials in which they hold copyright. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders; apologies are offered for any omission, and the publishers will be pleased to add any necessary acknowledgement in subsequent editions.

Acknowledgements

This book could not have been written without the generosity of Benjamin Armstrongs great-grandsons, Christopher and David Armstrong. Christopher trusted me with the eleven volumes of Benjamins diary and David shared with me his work on family history. Both Christopher and David searched out family photographs, many of which appear in the book.

The Dereham Antiquarian Society and particularly its secretary, Sue Walker-White, have also been very helpful in seeking out and providing further illustrative material.

David Neave kindly sent me a copy of his publication on Armstrongs time at Crowle.

As ever, the Norfolk Record Office has been very supportive, pointing me in the right direction for documents. The librarian and archivist at Norwich Cathedral Library helped me find my way through the antiquarian books which would have been part of Armstrongs library.

The anonymous readers comments were extremely useful and pointed out areas where expansion and further explanation were needed. Errors that remain are entirely my responsibility.

I am grateful to the Rt Revd Graham James, Bishop of Norwich, for reading the manuscript and writing the foreword, and to my editor Caroline Palmer for her encouragement.

My husband Peter has been extremely supportive and together we have explored the places with which Armstrong was associated, including the back streets of Dereham. All the modern photographs were taken by him.

Foreword

by the Rt Revd Graham James, Bishop of Norwich

I was a curate in Peterborough in the mid-1970s when I first discovered Benjamin Armstrongs diaries. Scouring a second-hand bookshop I found the extracts chosen by his grandson Herbert, vicar of St Margarets, Kings Lynn (now Kings Lynn Minster), during the Second World War. This selection, published in 1963, contained a masterly introduction by Owen Chadwick, placing Armstrong within the context of the Victorian church and wider society.

Susanna Wade Martins has further enlarged our understanding of the diarist by writing as full a biography as the sources permit. Armstrong deserves to be remembered both for his own qualities and as a representative of many clergy of his generation who exhibited a new pastoral zeal alongside a desire for the highest standards in public worship. It was a new age of spiritual seriousness in the Church of England. Armstrong did not seek novelty but the recovery of the Catholic and sacramental character of his church expressed in the beauty of holiness and service to the poor.

Four decades ago I was immediately drawn to Armstrong. He was the sort of priest I admired. His commitment to daily public worship was one shared in my council estate parish, where there was a Eucharist every day, something Armstrong would have barely imagined possible. He had served in Dereham for fourteen years before even introducing a weekly service of Holy Communion. It was upon the dedication and vision of Victorian clergy like Armstrong that the twentieth-century Church of England was built.

Prior to discovering Armstrong I had already read the diaries of another Norfolk clergyman, James Woodforde of Weston Longville. I felt no connection with Woodforde at all. He seemed not merely a remote figure (though he was both in time and social circumstance) but someone who did not exercise a ministry remotely akin to my own. Armstrong, writing only half a century after Woodforde, inhabited a world I recognised. Its a lesson in the rapidity of change in the Church of England in the nineteenth century.

Clerical diarists are not a scarce breed. Woodforde, Witts, Kilvert and others were mostly rural clergymen. Armstrong is different. He may not have been a city priest, but Dereham was a relatively populous and growing market town parish. He did not need to write a diary to fill his time. His was no leisured life. Neither was his diary an exercise in introspection nor even a spiritual journal. It was very much a record of daily life, carefully preserved for posterity but perhaps occasionally therapeutic as he records what he thinks of those who oppose his ministry or his frustrations with members of his family, especially his sister and her husband.

Susanna Wade Martins enables us to discover dimensions of Armstrongs life which make him the more fascinating. He would have preferred a career in the Army but finance and circumstance dictated otherwise. His vocation (and his Catholic churchmanship) came later, not least as a result of the reading he was expected to do for his ordination examinations and the company of those he met along the way. Coming as he did from a family wealthy enough to travel, his experience of the Roman Catholic Church in continental Europe (he spent two months in Paris when he was 23 before travelling through Belgium, Germany and Holland) spoke to his natural aesthetic sense. In continental Catholicism he admired the use of churches for prayer every day of the week, and their ordered liturgy. This experience seems to have shaped his mind and thinking for the rest of his life. When in London he would seek out the most advanced Anglo-Catholic churches in which to worship. In time he became chairman of the Norwich Diocesan branch of the English Church Union, which was uncompromising in its support of the Anglo-Catholic cause.