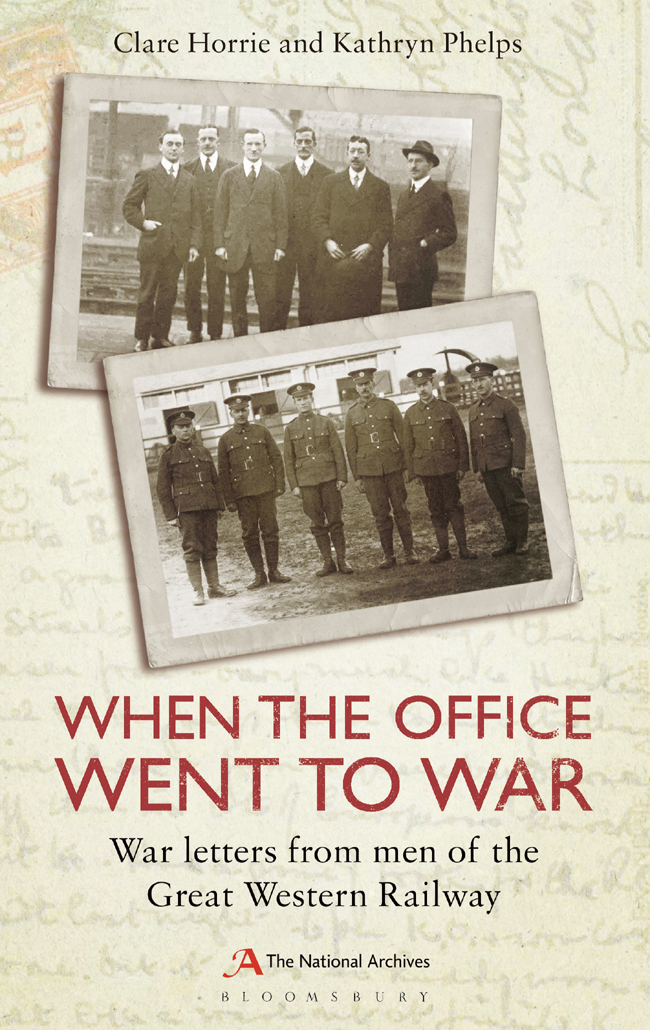

W HEN THE O FFICE

W ENT TO W AR

W HEN THE O FFICE

W ENT TO W AR

War letters from the men of the

Great Western Railway

Clare Horrie and Kathryn Phelps

CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to all those who worked at the Paddington Audit office for the Great Western Railway and served or lost their lives during the First World War.

Just a few lines to let you know that I am still in the land of the living.

EDGAR HARRY BRACKENBURY, 16TH MARCH 1916

These words from E.H. Brackenbury are some of the few written by the many British men in the forces during the First World War. Such wartime correspondence recreates the world of combat in striking detail told by the men who were there. The letters in this book come from the members of the Audit office for the Great Western Railway based at Paddington while on active service 1915-1918. What makes this collection of soldiers letters so different from all others is the fact that it reveals the stories of a particular group of men or GWR* fellows, ranging in class and education, who were writing back to their colleagues and bosses in the office over time.

The letters themselves are arranged in twelve carefully bound folders, rather like a series of scrapbooks. Starting from August 1915, each part represents what was known as the office newsletter, a collection of letters, photographs, postcards, field cards and contemporary newspaper cuttings from those who had gone to fight. Every newsletter opened with a news section listing those who had written and sent photos to the office and those who recently left to company to serve at the front. The totals at that point of all men in khaki from the Audit office were given too. Again the news section gave details of those who had died or had been injured, visited the office on leave or been promoted.

The newsletters were meant for circulation within the office departments and they were also read by men when they came home fromthe front on leave. People at home who had been sent their own letters or photographs lent them or typed them out to be circulated as part of the Audit office newsletter.

The whole process was clearly carefully managed. The news section listed those in the Audit office writing to the men. Letters and photographs for inclusion from the Goods, Passengers, Agreements General and Parcels, Fares and Ticket supply departments were to be handed to particular named people.

Those writing to the men clearly dealt with a large body of correspondence. Naturally, we do not have copies of any of the letters sent out, but evidently they were full of news according to the responses from the men and must have varied depending on the relationship with the sender. There was a real drive to keep in touch at all costs. Indicative of this commitment is the question posed in the August 1915 newsletter, are we in touch with all the fellows away, and if not, why not?

The letters

For the Audit boys who were far from home it must have been important to maintain that connection with Paddington and civilian life, a world away from the front. It provided a touchstone for what they the fighting for or allowed them to dream about life after the war. Many were keen to return to their jobs as Great Western Railway management had promised and showed concern in their letters over female workers taking their places in their absence. Some may have seen writing was a way of securing their future and wished to keep up with office politics.

Thus, through their letters this particular cast of characters mapped their personal experiences of the conflict within France, Belgium, the Dardanelles, India, Greece or Egypt. Some men who enlisted had previously been in the Territorial Army or fought in the Boer War. Others were mere boys or had no previous military experience. During their time in khaki some were seriously injured and others died. All of the men in their different ways seem to be incredibly stoic and brave.

Many of those who wrote back to the Paddington Audit office showed a desire to grit their teeth and get on with it, keep a stiff upper lip and chose not to describe the hell they were going through in their letters. The fact that the letters were shared within the office and written to male colleagues must have informed their overall tone. They were open letters. As a consequence, some letters appear chipper and understated or betray a subtle sense of bravado. For example, Donald Hambly writing at the end of 1916 whilst training on the south coast with the Royal Naval Air Service said

I am living in hopes of being sent out very much nearer the real thing, but for the present I must possess my soul in patience and carry on with what cheerfulness I can muster.

Censorship was a big issue for our writers as the correspondence makes clear. Handwriting was crayoned out in thick blue pencil by the censor in an obvious way. Writers often recorded their awareness of the censor too. Harold Watts, for example, declared that he would not give details and would save it for discussion when he next visited on leave. Some of the letters were addressed from somewhere in France or else the author buried their address in main body of the letter text as advised by the censor.

Nevertheless, it is still surprising that some did describe the reality of the war as they experienced it and provided details that defied the censor, for example E. H. C. Stewart:

Our casualties here amounted on the average, to about two per day killed, of course, we thought it terrible at the time at least I did.

Again, A.E. Rippington wrote in August 1915:

Well old chap, I am glad I am wounded to get out of that hell, and if you ever meet a chap that says he wants to go back call him a liar.

Interestingly E.H. Brackenbury, who wrote from France and described the countryside and his various leisure activities made the following loaded comment:

I hope you will not wonder whether I am aware that there is a War going on, for I am very well aware of it but at the same time think it quite a good scheme to talk about other things sometimes.

The language and form of address used in the letters is a world away from todays lexicon with the use of terms like old chap or old boy or being in a euphemistic warm spot or show. Writers often seem to be pre-occupied in expressing that they were in good health or in the pink possibly because they were only too acutely aware this could rapidly change, indeed as W.J.E. Martin of the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards wrote from France in November 1915,

To let you know I have not got shot yet and am in the best of health.

Some letters appear more formal than others as the men addressed their superiors or bosses. Dear Sir was used as an occasional form of address. Regular writer, Arthur Smith often signed off as yours obediently providing a certain Victorian formality. He even apologised for his handwriting, which in fact is possibly one of the clearest hands! In other instances it is obvious that the authors were writing to close friends and used nicknames such as Effie for F.E. Lewis; Burgie for Mr G. Burgoyne; Jacko for E.W. Jackson; Frosty for R.C.S. Frost; Fatty for J.W. Hyam; or Mug for Morris to name a few.