Bloomsbury Publishing

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2017 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2017

Anthony Burton and Rob Scott, 2017

Anthony Burton and Rob Scott have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4729-2283-0 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-8448-2281-6 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-2282-3 (ePDF)

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

Introduction

In the 19th century Britain was often described as the workshop of the world. But even as early as 1837 a former Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, was prophesying that the rest of the world would not accept that situation for ever, though it is doubtful if anyone in Victorian Britain could have foreseen that in the 20th century another Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, would publicly turn her back on the whole concept in favour of service industries. When industries decline, it is not just material things that are lost, but a whole world of expertise and craftsmanship. Yet in spite of the drastic decline in Britains traditional crafts and industries, some survive, preserving skills and technologies developed in some cases over many centuries. It is these survivors that this book celebrates.

It could be argued that the world has moved on in recent decades and to look back on former triumphs is no more than an enjoyable but ultimately futile exercise in nostalgia. The crafts, trades and industries that we shall be looking at, however, are not museum pieces: they have survived because they offer something valuable, something for which there is a continuing demand. In many cases this may be because people still appreciate the extra craftsmanship that produces artefacts which stand out from the general run of mass-produced objects. In a few cases, conservation work absolutely requires that older technologies be used so that the end product will fit comfortably next to the original work. In other instances, technology simply cannot replace human skills.

There is a good case to be made for celebrating these survivors, but why bother to describe the processes by which they are made? Much of our modern world is incomprehensible in its detail. A modern mobile phone is a wondrous thing but you cant take it to pieces and see exactly how it works. One of the great fascinations of older technologies is that they are basically comprehensible. If you visit a watermill, for example, the machinery may look complex, but it doesnt take long to work out what does what. Water makes the wheel turn that cog meshes with that cog, which in turn meshes with another, until eventually the grindstone itself is moved, and grain can be poured in and turned into flour. The processes are often as attractive and appealing as the end result. That is what we hope this book shows not only a range of things that are in themselves intrinsically interesting but also the great fascination to be had from seeing just how they are made and how they function.

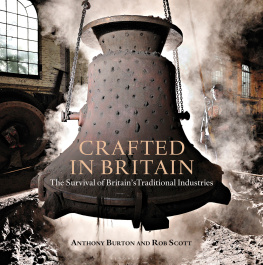

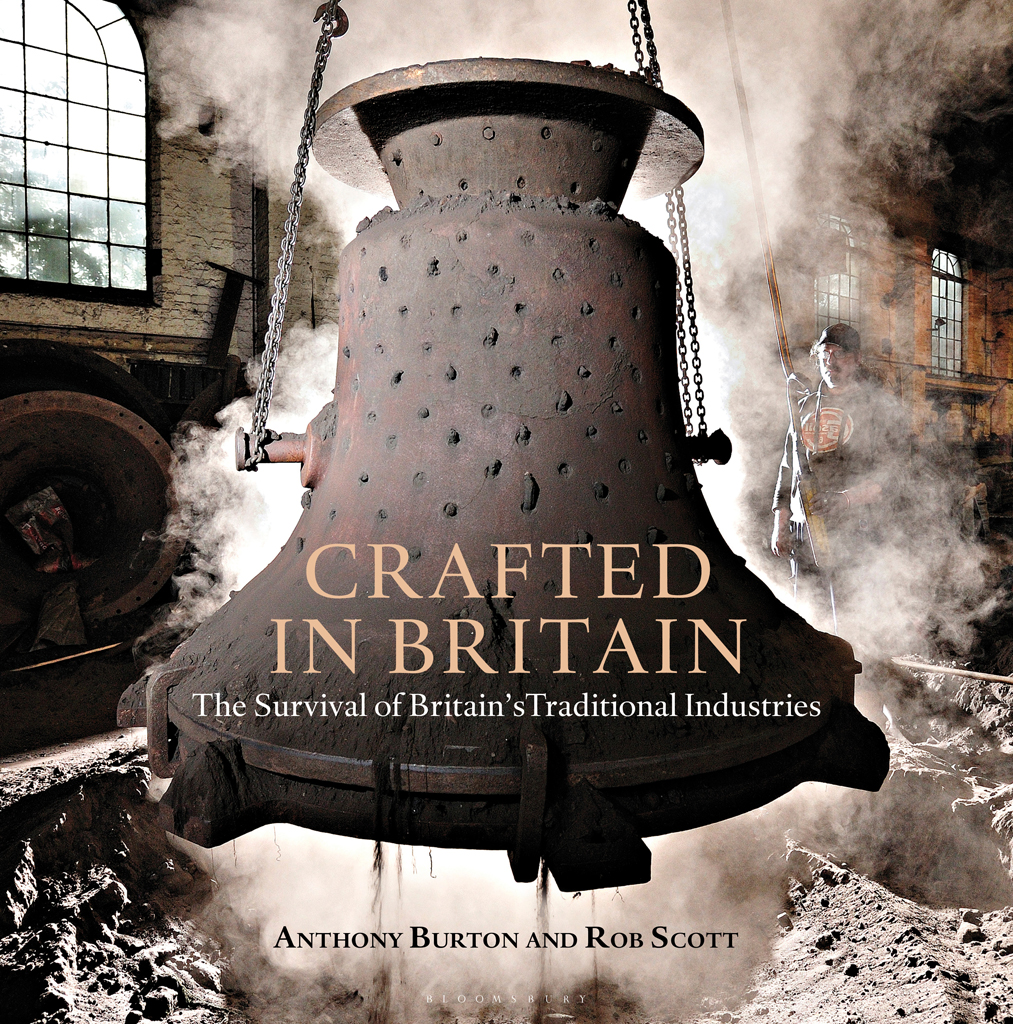

For both me and the photographer Rob there were surprises and delights along the way: it was extraordinary, for example, to see craftsmen turn a strip of silver into a beautifully shaped spoon and neither of us will ever forget the extraordinary atmosphere of the bell foundry and the feeling that it must have been much the same a century ago. Our hope is that in words and pictures we can share these and other wonderful experiences with the reader.

The Grain Mill and the Millwright

Food is the most basic of all human requirements; without it we die. And no form of food is more basic then bread; there is evidence that cereals were being grown for food back in the Stone Age. Originally, the grain would have been crushed by hand by rubbing between two stones, but this was also one of the first processes ever to be mechanised. For many, many centuries the only way to produce flour was to use stones in some sort of mill. Inevitably, changes came and new types of mill appeared, producing white flour that was considered more refined, in every sense of the word, and more sophisticated. But the old mills producing wholegrain flour have survived and the end product is now generally seen as offering a healthier option, not to mention a far better flavour. But there are very few mills that are still powered by water or wind that are actually working as fully commercial concerns, rather than relying on paying visitors to keep them going. Claybrooke Mill is one of them.

Spencer Craven inspecting the grain as it pours down to the pair of millstones at Claybrooke Mill.

Claybrooke Mill in Leicestershire can be found very close to High Cross, a spot at the very heart of Roman Britain, the point where the two great roads, the Fosse Way and Watling Street, intersect. This is rather appropriate, as it was the Romans who first introduced the water mill to Britain. The earliest mills were very simple: paddle wheels on a vertical shaft were set directly in a stream, and turned the stones above them by direct drive. The Romans improved on this system, with a vertical wheel on a horizontal shaft the type of wheel we all recognise today. It was first described in the 1st century BC by Vitruvius, and it sometimes known, perhaps rather pedantically, as the Vitruvian wheel. It was an immediate success, and by the time the Normans had conquered England and recorded their assets in the Domesday Book, they were able to list literally thousands of water mills producing grain. Claybrooke was one of those mills. It will have been rebuilt, modified and enlarged many times over the years, but it remains a remarkable story of continuity millers have been working here doing much the same job for more than a thousand years.