New Zealand Railways

Their Life and Times

by Robin Bromby

Highgate Publishing

Sydney

NEW ZEALAND RAILWAYS. THEIR LIFE AND TIMES

[Based on the authors Rails That Built a Nation , published in 2003 by Grantham House, but reformatted with extensive editing and additions]

First published 2014 by Highgate Publishing, P O Box 481, Edgecliff NSW 2027, Australia. (www.highgatepublishing.com.au)

Copyright Robin Bromby 2014

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this work.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Bromby, Robin, 1942- author.

Title: New Zealand railways : their life and times / Robin Bromby.

ISBN: 9780992595609

Notes: Includes bibliographical references.

Subjects: Railroads--New Zealand--History. Railroad travel--New Zealand--History.

Dewey Number: 385.0993

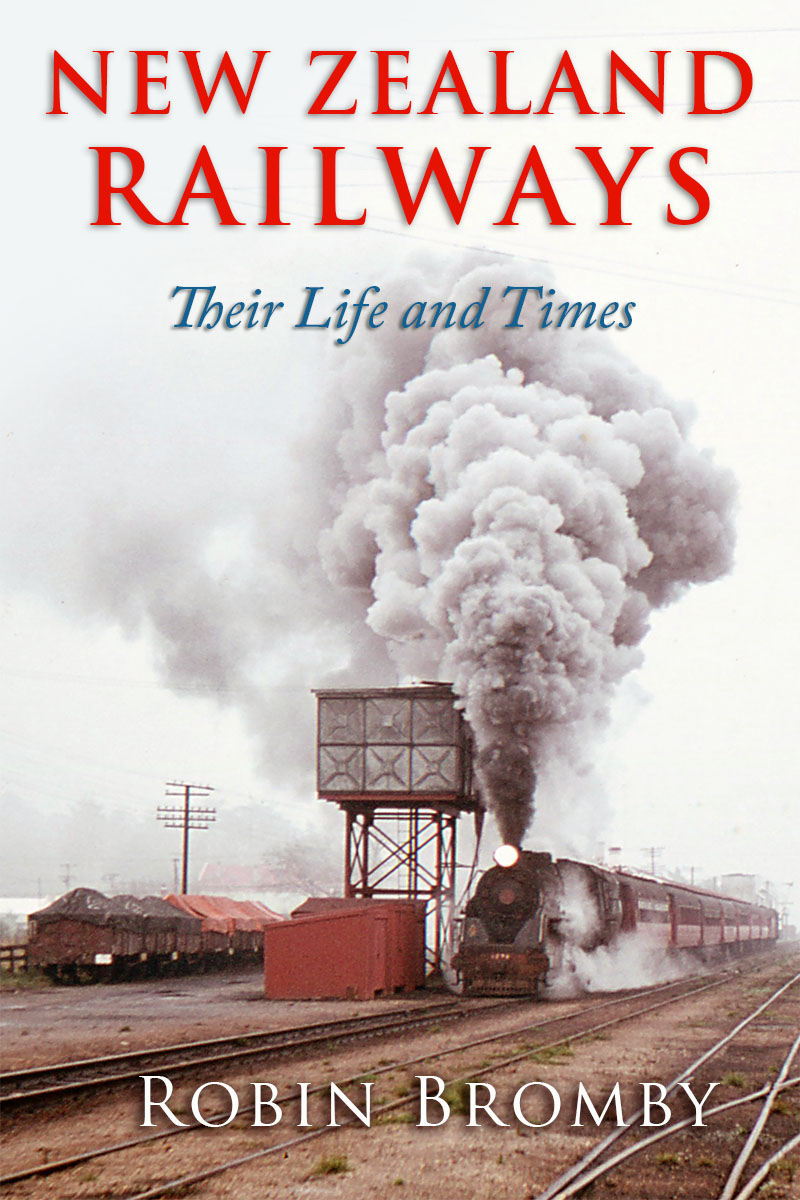

Cover: On a misty mid-morning on 21 May 1969, Ja 1274 pulls out of Milton on the Main South line hauling a Limited Express that began its journey at Invercargill and will by early evening run on to the wharf at Lyttelton to discharge passengers making for Wellington on the overnight ferry. ( Wilson Lythgoe )

Contents

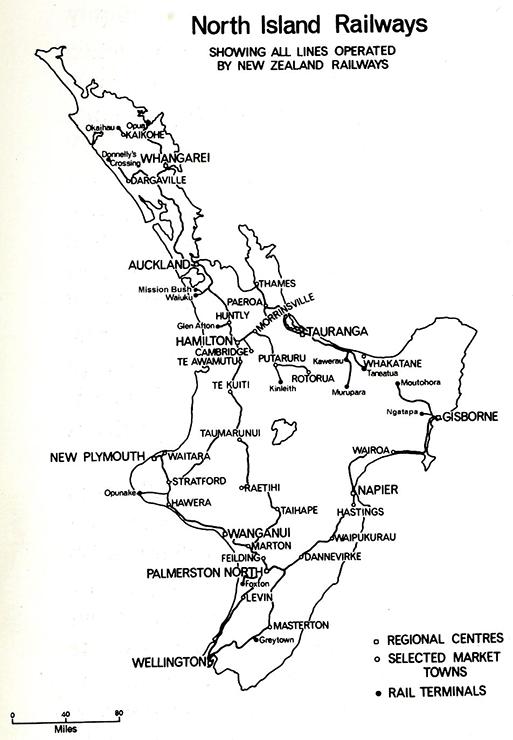

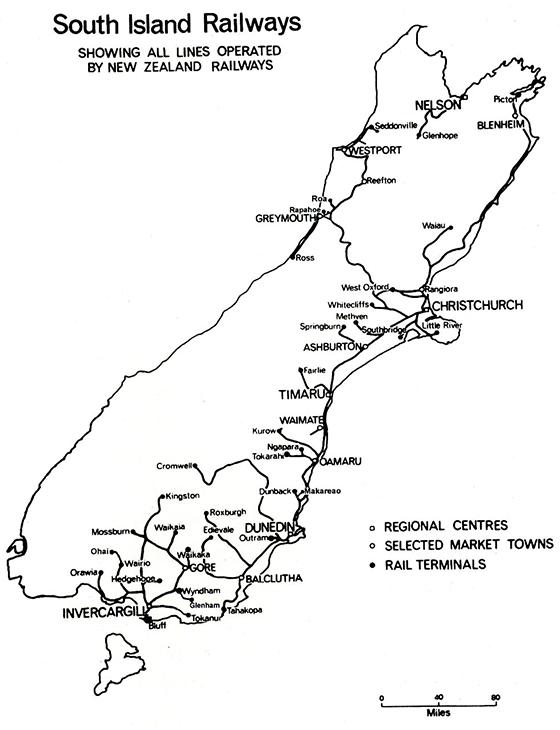

These maps illustrate the extent of rail building, showing a very complex network for a country with such a low and sparse population. New Zealand did not reach one million people until 1909. By 1945, when the last of the main lines was completed and with most of the branch lines still in existence, the country had just 1.7 million people. (Maps courtesy of Euan McQueen)

Introduction

NEW ZEALANDS RAILWAY SYSTEM was at its greatest length of 5,656 km until, on 5 December 1953, the Outram branch near Dunedin was closed. The branch, 14.5 km in length, serving only one small settlement and running almost its entire length through farmland, was one of many rural lines in New Zealand that owed their existence to local political interests. Landowners, in order to win their case for a railway, had offered to make land available free of charge provided trains ran six days a week. The line opened to traffic on 1 October 1877. By the early 1950s, however, the branchs economics were typical of many rural lines. Passenger services had ended in 1950 and in its last years the only goods traffic of note was the cartage of lime and fertiliser. Average weekly freight amounted to 107 tons inwards, just seven tons outwards. On average, sheep and cattle transport on the line amounted to twenty-three head a week. In 1951 the Outram branch lost 5,056, a figure almost double its revenue. On top of that, New Zealand Railways (NZR) determined that 16,000 needed to be spent on new sleepers to keep the line safe for trains. The end was thus inevitable.

Within weeks of Outram seeing its last revenue train, other lines were shut down: the Waihao Downs-Waimate section in South Canterbury, the Browns-Hedgehope section in Southland and the Greytown branch in Wairarapa. The Eyreton branch in North Canterbury was closed a few months later, in May 1954.

***

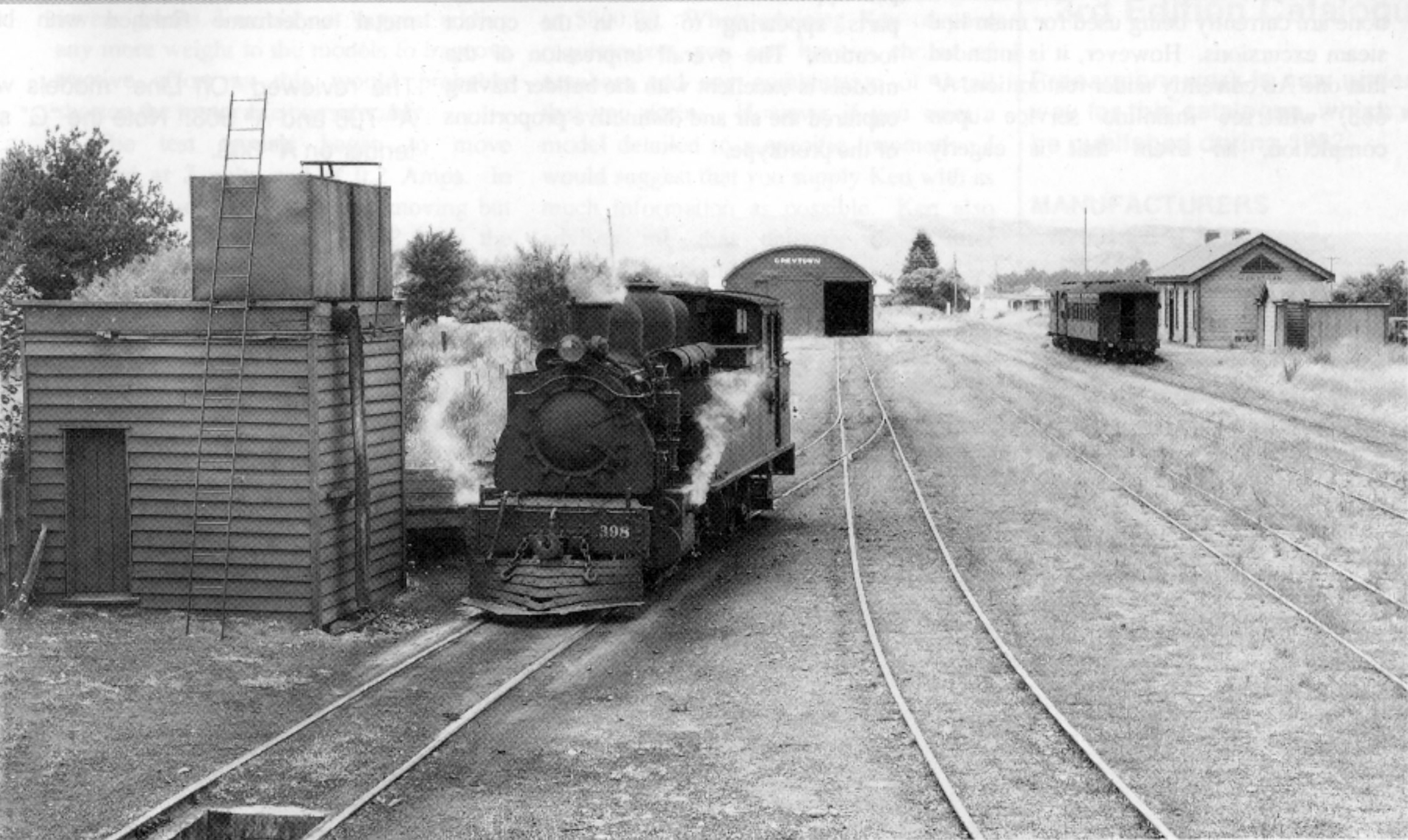

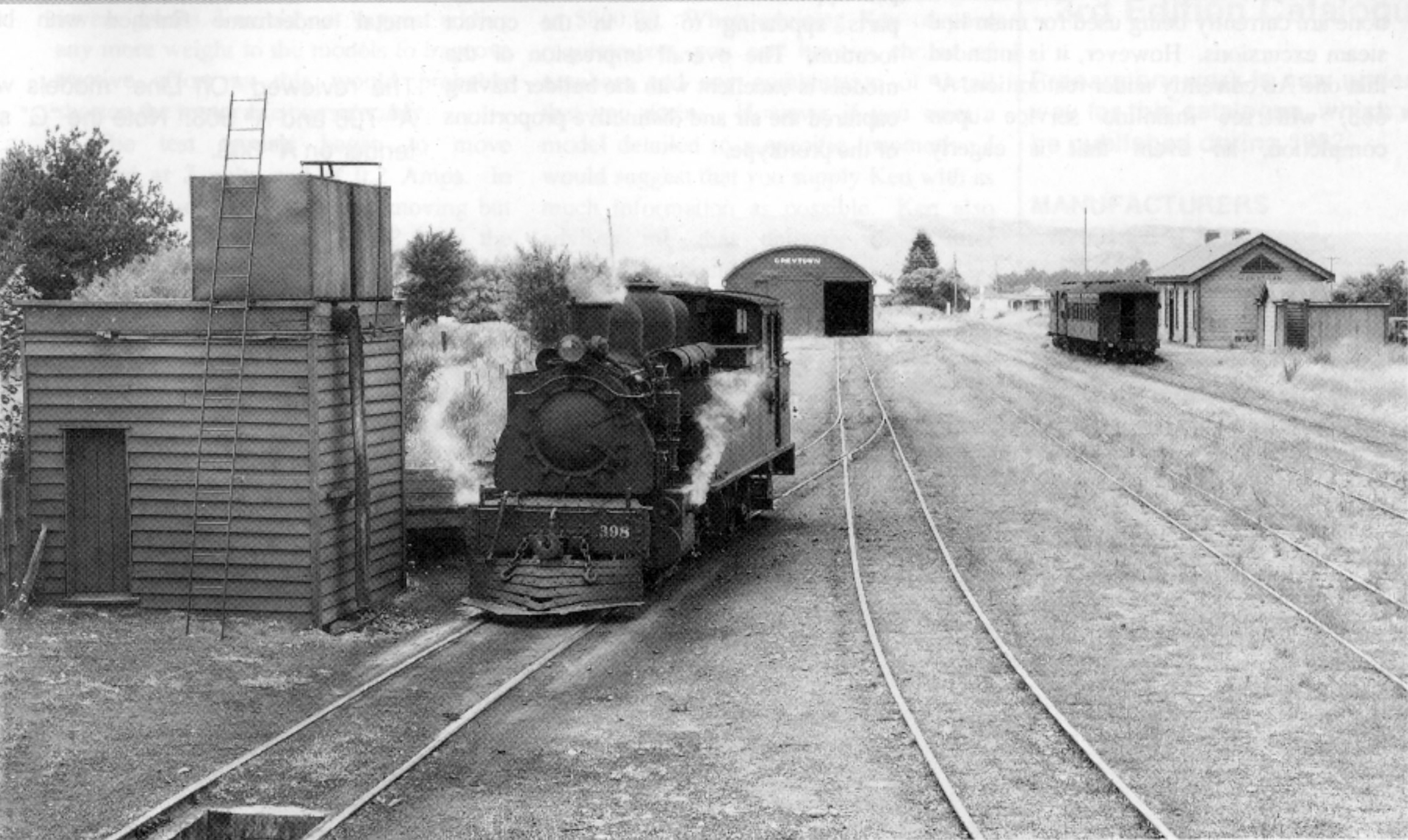

Wf 398 (2-6-4T) seen here in January 1947 in a quiet Greytown yard: the carriage and brake van that made up the train to Woodside, just 5km away on the main line to Wellington, sit at the passenger platform. There are no goods wagons in sight. The short branch was one of the first victims of the 1953 closures. (Wairarapa Archive)

The pattern was clear. The era of railways as the mainstay of land transport throughout New Zealand was ending. One by one, most of the rural branches would disappear over the next forty years; the ones that survived the longest would be those serving bulk traffic, such as logs on the Dargaville branch in North Auckland and coal on the Wairio branch in Southland.

There were some rays of hope in the years immediately following the Second World War. In his annual Railways Statement to Parliament in 1950, Minister of Railways William Gooseman announced that revenue for the year to March was the highest yearly figure ever for New Zealand Railways (or NZR as it was usually called): 19.54 million. Passenger revenues were also up mainly because the department was able to put more first class and sleeping cars back into service after the war, along with the restoration of the daylight expresses between Auckland and Wellington (supplementing the overnight trains) and the running of special trains for the Empire Games held in Auckland that year. The annual loss had been cut to 1.05 million.

But Gooseman signalled that the years of government indulgence were over. After fourteen years of Labour government and its widening of state-owned activities in the economy, the more free-enterprise oriented National Party had come to power in November 1949 and the new minister made it clear to Parliament that the government considers it proper that those who avail themselves of the services provided by the railways should pay for them.

In 1953, the government moved to close those lines that were without hope of paying their way.

Non-paying lines were as old as the railway system itself. That was all very well when there were few alternatives to rail, but as soon as road was able to offer cheaper and usually faster transport times (particularly over the shorter distances), then that was another matter. In 1926 the NZR chief accountant, Mr H. Valentine, said it was the non-paying branch lines that were the main factor responsible for the parlous state of railway finances. Twenty-eight branches were so classed and together they earned NZR 258,243 against their 541,710 combined deficit once their share of interest charges plus expenditure were added together. And that calculation allowed a credit of 36,568 for their assessed value as feeders; that is, the traffic they generated that would go on to earn revenue on main line services. Those lines covered a combined 1,245 km. There were exceptions, and Valentine drew attention to two branches that actually paid their way: Waitara in Taranaki and Foxton in Manawatu. The total cost (operating expenses and interest) was 23,044 but their revenue (14,265) plus an allowance for feeder value of 14,273, left these earning a combined profit of 5,494. That these lines, together, covered only 40 km between them showed that a branch did not need to be long to be economic; they just had to serve the right places and have a demand for their use. Too many branches did not and, indeed, both Foxton and Waitara would once more subside into the red and be closed.

The last days of a branch line. Here A 601 is seen at Himatangi on the Foxton branch three months before the lines closure on 18 July 1959, the locomotive with one wagon attached standing at the goods shed. (B Poulson Bob Stott Collection