Dedication

To my father who inspired in me a love of the old country

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

PEN AND SWORD FAMILY HISTORY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Ian Maxwell 2009

ISBN 978 1 84415 989 5

Digital Edition ISBN 978 1 84468 678 0

The right of Ian Maxwell to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 10pt Palatino by Mac Style, Beverley, East Yorkshire Printed and bound in the UK by CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

ABBREVIATIONS

| NAS | National Archives Scotland |

| NLS | National Library Scotland |

| OPRs | Old Parish Registers |

| GROS | Registry Office Scotland |

| OSA | Old Statistical Account |

| NRA | National Register of Archives |

| SCAN | Scottish Archive Network |

| TNA | The National Archives (London) |

| NSA | New Statistical Account |

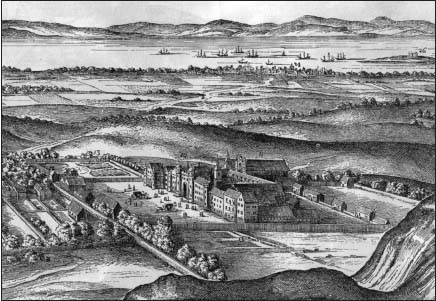

Great Hall, Parliament House. From James Grant, Old & New Edinburgh, issued in weekly instalments c.1890.

INTRODUCTION

S cotlands history had been influenced by many factors: the division of the country by its language, with its Gaelic-speaking population in the Highlands and its anglicized population in the Lowlands; the Reformation which impacted most dramatically in the Lowlands, with many of the Highland clans remaining local to the old church; and, of course, its geography with successive ways of invaders and settlers gravitating to the more fertile arable regions of the Lowlands rather than the comparatively barren Highlands.

These physical factors had their effects on the earliest known settlers in Scotland. The majority of the Bronze and early Iron Age settlements for example are to be found along the east coast in the Lowlands. The Romans penetrated as far as Aberdeenshire but they built their northermost defences, the Antonie Wall, along the line of the Forth and Clyde valleys on the edge of the central Lowlands. South of the Forth-Clyde there were several British tribes, recorded by the Romans: the Selgovae, Novantae, Damnonii and Votadini. By the sixth century these had developed into the British kingdom of Strathclyde and Rheged, in south-west Scotland, and Gododdin in Lothian.

The best known inhabitants of Scotland by the fifth century AD were the Picts. They lived in the central and eastern parts of the country. To the sixth century cleric Gildas, the Picts were a foul horde. They remain a mystery to this day, leaving only strange symbols carved on standing stones and place names such as at Pitlochry or Pitmadden. Pictish place-names can be recognised by the words pert (wood) caer (fort) pren (tree) aber (river mouth) and a few others. The Picts spoke a form of Celtic like the British and Welsh though different from their Scotti neighbours so that St Columba when he arrived from Ireland needed an interpreter to speak to them.

In the sixth century the Scotti, also known as the Dal Riata, invaded from the north of Ireland and settled in the western region known as Argyll. They introduced their own names, such as achadh (field or settlement) sliabh (mountain) baile (settlement) and most distinctive of all cill (church) usually combined with a saints name. Of course, it was this Irish tribe who gave us the name Scotland. Gildas, writing in the sixth century AD, declared: As the Romans went back home, there eagerly emerged from the coracles that had carried them across the sea valleys the foul hordes of Scots and Picts, like dark throngs of worms who wriggle out of narrow fissures in the rock they were readier to cover their villainous faces with hair than their private parts with clothes.

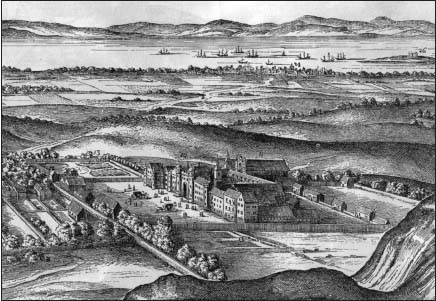

Holyrood Palace and Abbey. From James Grant, Old & New Edinburgh, issued in weekly instalments c.1890.

The Celts were followed by the Angles, who settled in south-eastern Scotland. They were in turn followed by the Norsemen from Scandinavia, who raided both the east and west coasts indicriminately. Although they settled along the west coast and as far south as the Moray Firth on the east coast, it was principally in the Orkney and Shetland Islands, and in Caithness that they settled permanently. These places remained under Norwegian sovereignty for centuries after the rest of Scotland was united under one king.

In 844 the Picts and the Scots were unified under the rule of Kenneth MacAlpin forming a united Scotland north of the Forth and Clyde valleys. In 1018 under Malcolm II, the Scots defeated the Angles at Carham on the Tweed and conquered the land of Lothian. In the same year Malcolm also inherited the kingdom of Strathclyde, or Cumbria. With the gradual anglicizing of the southern area, it was not perhaps surprising that the more aggressive Teutonic peoples gradually drove the Celtcs into the mountainous regions of the Highlands.

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries there was one further mixture to the many stains that finally made up the Scottish race, caused by the arrival of various Norman adventurers and their followers to take up high office in church and state. Under David I huge estates in southern Scotland were dispensed to Normans: Renfrewshire went to Walter FitzAlan, who in Scotland took the name Steward from the office he and his family held at the Royal court. By the fourteenth century Walters descendants were calling themselves the Stuarts and would rule Scotland and eventually England until the early eighteenth century. Another incomer was Robert de Brus, Lord of Brix in the Cotentin peninsula of Normany and of Cleveland in Yorkshire. It was under a de Brus, of course, that the Scottish nation was utimately united in the fourteenth century.