Ian Maxwell - Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland

Here you can read online Ian Maxwell - Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: The History Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland

- Author:

- Publisher:The History Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ian Maxwell: author's other books

Who wrote Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Britain had held a strong presence in Ireland for more than seven centuries, and yet that impoverished near neighbour remained to most Englishmen a remote, if not sinister, place. English barrister George Cooper, writing in 1799 declared, remote corners of the Hebrides have been often explored [and] the name of Ireland is most familiar to our ears, yet both the kingdom and its inhabitants have been as little described as if the Atlantic had flowed between us. Almost twenty years later, John Curwen MP remarked that he was visiting a country that, although almost within our view, and daily in our contemplation, is as little known to me, comparatively speaking, as if it were an island in the remotest part of the globe. Most Englishmen preferred to stay at home where their contact with the Irish was confined to those they encountered in the streets of London or in many of the growing industrial towns of the Midlands, the North of England and the central lowlands of Scotland. They associated them with poverty, crime, drunkenness and Catholicism which helped create the stereotype of the stage Irishman.

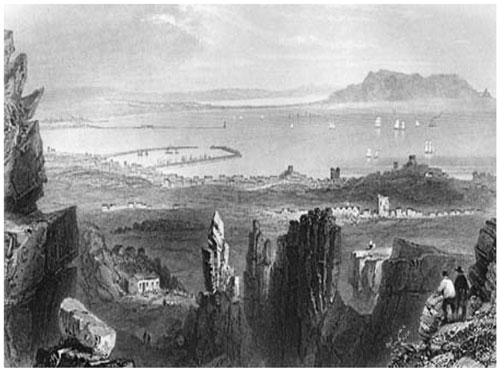

Dublin Bay.

Nineteenth-century accounts of Ireland conjured up images as alien to their readers in the drawing rooms of London, Manchester and Birmingham as the deserts of Western Australia or the hinterland of Africa. American missionary Asenath Nicholson admitted as much when she came to Ireland on the eve of the Great Famine; When we reached Dublin Bay, I gave myself to rummaging the scanty knowledge I had of Ireland, to ascertain whether I knew anything of its true condition and character. She went on breathlessly:

I knew that between the parallels of and of north latitude there is a little green spot, in the ocean, defended from its surging waves by bold defying rocks; that over this spot are sprinkled mountains, where sparkle the diamond and where sleep the precious stone; glens, with rich foliage and pleasant flowers, where the morning song of the bird is blending with the playful rill; that through its valleys and hillsides were embedded the gladdening fuel and the rich mine; that over its lawns and wooded parks were skipping the light-footed fawn and bounding deer; that in its fat pastures were grazing the proud steed and the noble ox; that on its healthy mountain slopes the nimble goat and the more timid sheep find their food. I knew that proud castles and monasteries, palaces and towers, tell the passer-by that here kings and chieftains struggled for dominion, and priests and prelates contended for religion; and that the towering steeple, and the more lowly cross, still say that the instinct of worship yet lives, that here the incense of prayer and the song of praise continue to go up.

She did admit, I had been told that over this fair landscape hangs a dark curtain of desolation and death; that the harp of Erin lies untouched, save by the finger of sorrow, to tell what music was once in her strings; that the tear is on her cheek she sits desolate, and no good Samaritan passes that way, to pour in the oil and wine of consolation. She was soon to encounter poverty on a scale she had never imagined.

To those visitors who braved the unknown, nineteenth-century Ireland was a world of extremes. The Irish countryside was made up of great estates where, by the 1870 s, more than half the land was owned by fewer than , major landlords, many of them related to each other blood or marriage. Served by an army of servants, they enjoyed a luxurious and leisurely lifestyle, housed in mansions with richly furnished interiors and elaborate gardens. For the vast majority, however, life was one of grinding poverty. By 1841, per cent of the houses in Ireland were one-room mud cabins. Furniture in these mud cabins usually consisted of a bed of straw, a crude table and stool and a few cooking utensils. The largest group found in the countryside and at the bottom of the social scale were the agricultural labourers, many of whom were casually employed and who tramped the roads in search of work during the hungry months.

It was a world which, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, seemed for ever set in stone, as conjured up in the words of Dublin hymn writer Cecil Alexander in All Things Bright and Beautiful :

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

God made them high and lowly,

And ordered their estate.

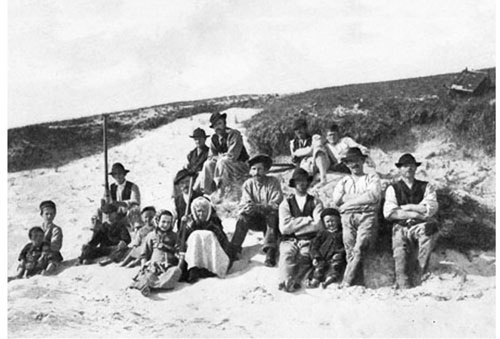

Navvies, County Donegal. (Samuel G. Bayne On An Irish Jaunting-Car Through and Connemara , 1902)

It turned out to be a less than prophetic view. The nineteenth century would usher in a period of monumental change in Ireland. The railways which were laid out through the famine-stricken countryside would transform the local economy, providing employment, developing towns and giving the impetus for Irelands first tourist boom. An amazed traveller towards the end of the century would declare:

To any part of the island the railways convey us with as much comfort as on the best English lines. At the remotest towns and villages the post arrives with laudable regularity, and the electric-telegraph wires reach to every corner where there are English-speaking inhabitants. At the railway stations there are bookstalls, with newspapers and miscellaneous literature; and the traveller, whether commercial or non-commercial, will notice no great differences from what he has been accustomed to in provincial journeys in England. In some things, and these not unimportant such as police, primary schools, workhouse buildings and management he will even be forced to admit superiority in Ireland. If he asks no questions about church and chapel, and reads no local newspapers, he would hardly feel that he was in a strange country, and cannot realize all he has heard about Irish wrongs and Irish wretchedness, and about the hopeless difficulty of governing a country apparently so civilised and prosperous.

There were many at the time that would have disputed such a rosy account of Ireland in the 1870 s. Only a few years before, both Irish and English newspapers had been awash with rumours of illegal arms shipments and impending rebellion. In the countryside, agrarian violence was commonplace in many parts of the country as landlords evicted their tenants in increasing numbers. In an attempt to address these grievances, British governments would issue a series of land laws which, by the beginning of the twentieth century, would lead to the end of the great estates in favour of small, family-owned farms.

A succession of British governments also took an increasingly interventionist role in education and social reform. A National School system was established across the country which provided free elementary education for all children, a full four decades before the establishment of a similar system in England. For those less fortunate, the Irish Poor Law system would help eradicate the perennial problem of begging and vagrancy by incarcerating entire families behind the forbidding walls of the workhouses which were established in every market town.

Within a generation life in Ireland had changed irrevocably for many. By the end of that eventful century the hated tithe proctor had long vanished; the hedge school, the swarms of beggars, public hangings, faction fighting and the sound of the banshee had all but vanished from the landscape. Looking back over the century, James Macauley observed in his book Ireland in 1872 that Ireland had changed beyond all recognition from the Ireland popularised by writers such as Charles Lever and William Charleton, which enjoyed great success with English audiences: The rollicking, reckless, fighting, fox-hunting squire or squireen; the half-pay captain of dragoons, professional duelist, gambler, and scamp; the punch-imbibing and humorous story-telling priest; the cringing tenantry and lawless peasantry; how unreal and unrepresentative all these characters seem now!

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland»

Look at similar books to Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Everyday Life in 19th Century Ireland and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.