Table of Contents

Table of Figures

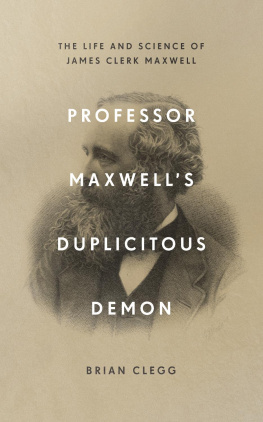

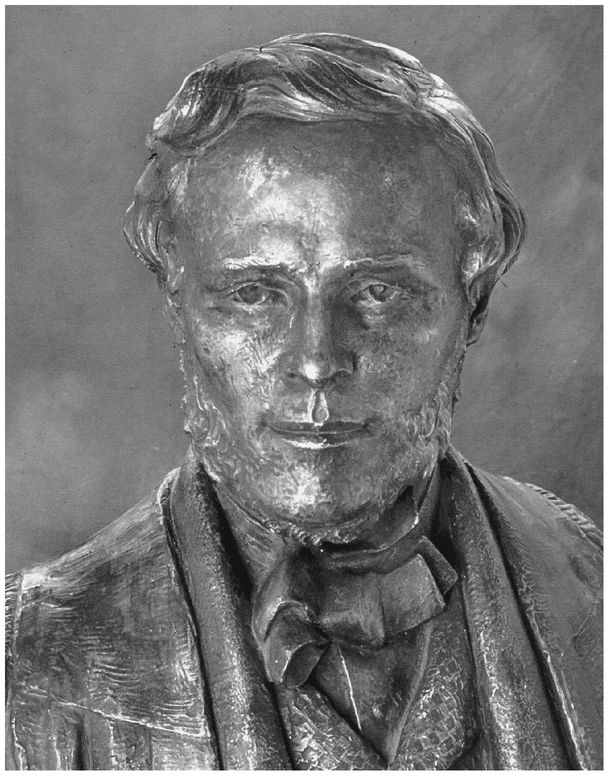

James Clerk Maxwell. From a bronze bust by Charles DOrville Pilkington Jackson. Courtesy of the University of Aberdeen

DEDICATION

To Ann

PREFACE

I fell under Maxwells spell when I was about 16 but for more than 40 years he was a man of mystery. His name cropped up in all the popular accounts of twentieth century discoveries such as relativity and quantum theory, and when I became an engineering student I learnt that his equations were the fount of all knowledge in electromagnetism. They seemed to work by magicsomething I attributed, with good grounds, to imperfect understanding. But now that I understand the equations a little better they seem even more magical.

Over the years the spell tightened its grip. My extensive, if desultory, reading on scientific matters served to deepen the mystery. Usually introduced as the great James Clerk Maxwell, his influence on the physical sciences seemed to be all-pervasive. Yet he was scarcely known in the wider world; most of my friends and colleagues had never heard of him, although all knew of Newton and Einstein and most knew of Faraday. What is more, nothing in what I had read revealed much about Maxwells life beyond the bare facts that he was Scottish and lived in the mid-nineteenth century.

The time had come to unravel the mystery. A few years ago I looked him up in all the reference books I could find, starting in the local library. The Encyclopaedia Britannica had a helpful 2000 word entry and a short bibliography. It was like finding the way to a store of buried treasure. Maxwell was not only one of the most brilliant and influential scientists who ever lived but an altogether fine and engaging man. And he seemed to inspire in writers a unique combination of wonder and affection; a Times Literary Supplement editorial of 1925, preserved in Trinity College Library, sums it up by saying that Maxwell was to physicists, easily the most magical figure of the nineteenth century.

I have tried to tell the story simply and directly, putting the reader at Maxwells side, seeing the world from his perspective as his life unfolds. Hence the main narrative contains few references to sources and no more background or detail than is needed for the story. The separate Notes section attends to these aspects and gives some interesting sidelights.

To his friends, and he had many, Maxwell was the warmest and most inspiring of companions. I hope this book will leave readers glad that they, too, know him a little.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Anyone who writes, or indeed reads, about Maxwell owes a great debt to Lewis Campbell, who gave us an affectionate yet penetrating picture of his lifelong friend in The Life of James Clerk Maxwell, co-written with William Garnett and published 3 years after Maxwells death. Campbell and Garnetts book has been the principal source of information for all subsequent biographies and I would like to add my tribute and my thanks to those given by other authors.

I am also much indebted to the more recent biographers Francis Everitt, Ivan Tolstoy and Martin Goldman for their added insights, to Daniel Siegel and Peter Harman for their scholarly but reader-friendly analyses of Maxwells work, and to the other authors listed in the bibliography. Several patient friends have kindly read drafts and suggested improvements; among these I am particularly grateful to Harold Allan and Bill Crouch. John Bilsland supplied excellent line drawings for the figures, and David Ritchie and Dick Dougal located many of the sources for the illustrations.

The Royal Societies of London and Edinburgh gave valuable help, as did the Royal Institution of Great Britain, Kings College London, the University of Aberdeen, Trinity College Cambridge, the University of Cambridge Department of Physics, Cambridge University Library, the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Institution of Electrical Engineers and Clifton College.

A visit to Maxwells birthplace at 14 India Street, Edinburgh, is a moving experience for anyone with an interest in Maxwell. It is possible only because the trustees of the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation service acquired the house in 1993 and have with trouble and care created a small but evocative museum. I should like to thank them for this service.

I am especially grateful to Sam Callander and to David and Astrid Ritchie for their generous encouragement and kindness.

The final words of thanks go to Wiley for publishing the book, and especially to my editor Sally Smith and her assistant Jill Jeffries for their friendly and expert help and guidance.

CHRONOLOGY

Principal events in Maxwells life

| 1831 | Born at 14 India Street, Edinburgh, 13 June. Grew up at Glenlair |

| 1839 | His mother, Frances, died |

| 1841 | Started school, Edinburgh Academy |

| 1846 | Published his first paper, on oval curves |

| 1847 | Started at University of Edinburgh |

| 1848 | Published paper On Rolling Curves |

| 1850 | Published paper On the Equilibrium of Elastic SolidsStarted at Cambridge University, Peterhouse for one term, then Trinity |

| 1854 | Finished undergraduate studies at Cambridge: second wrangler, joint winner of Smiths Prize: started post-graduate work |

| 1855 | Published paper Experiments on Colour as Perceived by the Eye |

| Published first part of paper On Faradays Lines of Force, second part the following year Elected Fellow of Trinity |

| 1856 | His father, John, died Appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy at Marischal College, Aberdeen |

| 1858 | Awarded Adams Prize for essay On the Stability of the Motion of Saturns Rings, paper published 1859 |

| 1858 | Married Katherine Mary Dewar, daughter of Principal of Marischal College |

| 1860 | Published papers Illustrations of the Dynamical Theory of Gases and On the Theory of Compound Colours and the Relations of the Colours of the Spectrum |

| Made redundant from Marischal College Failed in application for Chair of Natural Philosophy at University of Edinburgh |

| Severely ill from smallpox |

| Appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy at Kings College, London |

| Awarded Rumford Medal by the Royal Society of London for his work on colour vision |

| 1861 | Produced worlds first colour photograph Published first two parts of paper On Physical Lines of Force, the remaining two parts the following year |

| Elected FRS |

| 1863 | Published recommendations on electrical units and results of experiment to produce a standard of electrical resistance in his Committees report to the British Association for the Advancement of Science |

| 1865 | Published paper On Reciprocal Figures and Diagrams of Force Published paper A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field |