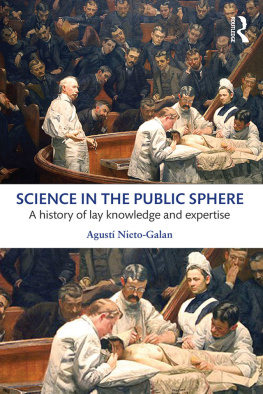

The Oxford Illustrated History of

Science

The thirteen historians who contributed to The Oxford Illustrated History of Science are all distinguished authorities in their field. They are:

PETER BOWLER, Queens University Belfast

SONJA BRENTJES, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin

JAMES EVANS, University of Puget Sound

JAN GOLINSKI, University of New Hampshire

DONALD HARPER, University of Chicago

JOHN HENRY, University of Edinburgh

STEVEN J. LIVESEY, University of Oklahoma

IWAN RHYS MORUS, Aberystwyth University

AMANDA REES, University of York

DAGMAR SCHAEFER, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin

CHARLOTTE SLEIGH, University of Kent

ROBERT SMITH, University of Alberta

MATTHEW STANLEY, New York University

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Oxford University Press 2017

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2017

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016955204

ISBN 9780199663279

ebook ISBN 9780191640322

Printed in Italy by L.E.G.O. S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Dave Rees, who was looking forward to reading this book

Acknowledgements

It was Simon Schaffer who first made me understand what an important and fascinating field the history of science was. I would like to thank him as well as my fellow students at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science in Cambridge for making my time there so invigorating and intellectually exciting. Since then I have had too many conversations with too many people in too many places about the history of science to be able to give individual thanks to everyone who has helped shape my thoughts over the years. I would, however, like to mention two in particularRob Iliffe and Andy Warwick. Special mention should go to my wife, Amanda Rees, without whom I would be completely lost.

I would like to thank everyone at Oxford University Press who has been involved with this project, particularly Matthew Cotton and my copy editor Tim Beck. Finally, of course, I would like to thank the chapter authors for their hard work, professionalism, and enthusiasm.

Contents

The first book in the history and philosophy of science that I can remember reading as an undergraduate thirty years ago was Alan Chalmerss What is This Thing Called Science? The copy is still on my shelves somewhere. The title has stuck with me for a number of reasons. The question it asks appeals because the answers turn out to be so unexpectedly elusive and slippery. At first sight it appears obvious what science isits what scientists do. Very few people now would deny the critical role that science plays in underpinning contemporary life. Science, and the technological offshoots of science, are everywhere around us. Modern science does not just provide us with technological fixes, though. Its ideas and assumptions are embedded in a very fundamental way in the ways we make sense of the world around us. We turn to science to explain the material universe, and to account for our spiritual lives. We routinely use science to talk about the ways we talk to each other. But what do we really mean by science? Its a uniquely human activity, after all. At its broadest level, science sums up the ways we make sense of the world around us. Its the set of ways we interact with the worldto understand it and to change it. It is this humanity at the heart of science that makes understanding its history and its culture so important.

Despite the fact that science matters so much for our culture, we often treat it as if it were somehow beyond culture. Science is assumed to progress by its own momentum as discovery piles up on discovery. From this point of view, science often looks like a force of nature rather than of culture. It is something unique about science itself that makes it progress, and there is something inevitable about its progress. Science therefore doesnt need culture to move forwards, it simply carries on under its own steam. Culture gets in the way sometimes, but in the end science always wins. If science exists outside culture like this, then it should not really matter where it happened. This means that the history of science should not really matter either. At best, it can tell us who did what when, but that is a matter of chronicle rather than history, which tries to interpret the past as well as simply record it. Advocates of this sort of view of science often talk about the scientific method as the key to understanding its success. Some pundits now talk about peer review or double blind testing as the hallmarks of scientific objectivity, for example, despite the fact that these are cultural institutions of very recent provenance.

As a historianobviouslyI think that the history of science does matter a great deal. If we want to understand modern science we do need to understand how it developed and under what circumstances. Even the most cursory survey of the history of science should be enough to demonstrate that the scientific method itself has been understood very differently by different people at different times. A century ago, most scientists would have agreed that science progressed by accumulating observations. According to this hypothetico-deductive account, science proceeded by formulating hypotheses based on observation and testing those hypotheses through further experiment. If the hypotheses passed the test of experiment then they were confirmed as true descriptions of reality. More recently, the idea that science proceeds by falsifying rather than confirming hypotheses has gained currency. History tends to show us that in practice, it is difficult to discern any kind of consistent method in what scientists do. On the contrary, different accounts of scientific method are very much the products of particular historical circumstances. After all, no one could have argued that the modern system of peer review was at the heart of the scientific method before the cultural institutions that support that practice (like scientific journals, professional societies, and universities, for example) had appeared.