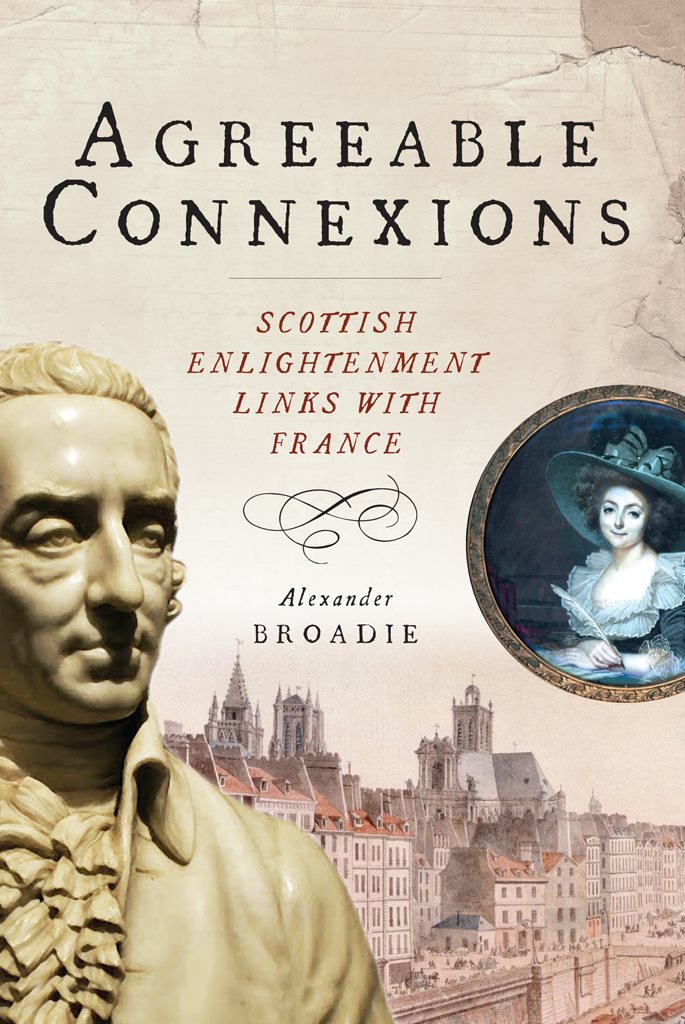

AGREEABLE CONNEXIONS

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Alexander Broadie 2012

First published in 2012 by John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

The moral right of Alexander Broadie to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-906566-51-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-907909-08-5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For Patricia Stewart Martin

A man, in the decline of life, to be expelled a country, which he had chosen for the place of his residence, and where he had formed a number of agreeable connexions, must suffer a violent shock... However, I cannot yet renounce the idea, which was long so agreeable to me, of ending my days in a society which I love, and which I found peculiarly fitted to my humour and disposition.

David Hume writing on 27 November 1767 to the Comtesse de Boufflers about his love for France

Acknowledgements

I thank Isabelle Bour, Jean-Franois Dunyach, Giovanni Gellera, Laurent Jaffro, Christian Maurer, Daniel Schulthess and Silvia Sebastiani for conversations concerning Scotlands Enlightenment links with France. I am grateful to Patricia S. Martin for help with many aspects of the book, including her suggestion of Humes phrase Agreeable Connexions as the title.

A. B ROADIE

Glasgow

A note on the text

Except where otherwise stated all the translations from Latin and French texts are my own.

A. B ROADIE

CHAPTER ONE

The nature of Enlightenment

Scotland has played an immense role in European high culture through the centuries, and among the cultural ties it has had with the various European countries none have been greater than those with France. This is particularly true in respect of the eighteenth century, the Age of Enlightenment, and this book will principally be focused on aspects of these eighteenth-century ties. However, lest it be thought that the links during the Enlightenment arose from nowhere, Chapter 2 will demonstrate that the ties stretch back in an unbroken line into the Middle Ages. As will also become clear, on the other side of the temporal divide, the ties remained in place well into the nineteenth century. Indeed, it is not difficult to show that today they are still in place and still full of vigour, but I shall not take my story so far. The ties are wide-ranging but I shall pay particular attention to philosophical, moral and social matters; other aspects of high culture, however, including scientific, will also be on display.

That Scotland and France were major players in the European Enlightenment is not in dispute arguably the only country to match their achievement is Germany and since the Enlightenment is here centre stage, it is appropriate to begin by unpacking the concept of Enlightenment. Germany will provide my guide to the concept: not just my guide but almost everybodys in this area. Immanuel Kant, greatest philosopher of the European Enlightenment, wrote a short essay entitled Was ist Aufklrung? (What is Enlightenment?), which is the starting point for most philosophical discussions of the concept.

Kant identifies two features of Enlightenment. The first is peoples use of their own faculty of reason as a means of reaching conclusions, as contrasted with peoples turning to authorities for guidance on what to think, and the second is the tolerance that those in authority show to people with ideas. If people cannot put their ideas into the public domain without fear of being silenced by authorities who do not like the ideas that have been published, an Enlightenment is less likely to arise and may be impossible. I should like to add a third feature, which depends on the two just mentioned: namely, the presence of robust public debate. The Age of Enlightenment was marked by the fact that people who were thinking for themselves were also disputing with each other, motivated by the thought that public debate enhances the prospects for progress in the whole range both of intellectual disciplines and also of civic practices. The relation between debate and progress is clear. For we cannot be sure of the quality of our ideas if we do not pass them to others who will criticise them or defend them and thereby help us to decide whether our ideas should be retained, abandoned or modified. Hence, and deploying the most distinctive term in Kants technical vocabulary, it may be said that central to Enlightenment is critique or critical analysis carried out in the public domain. The most prominent examples of critique that Kant himself offers in his seminal essay are a pastors critique of his churchs theology, a soldiers critique of strategic thinking by his military leaders, and a citizens critique of the tax system. If the critiques are in each case hostile, motivated by a wish to see improvements in thinking and in practice, and if, despite being criticised, the religious, military and political leaders tolerate the fact that the critiques have been published, their toleration is a sign of Enlightenment.

The role of authorities in this narrative is crucial. People must be able to publish their ideas without fear of the reaction of those in authority. This central fact about Enlightenment prompts the question why authorities should be minded to move against those with whom they disagree, and one obvious answer is that they judge their authority to be under threat. Put otherwise, intolerant authorities will seek to silence public debate, and since public debate is a core feature of an enlightened society, intolerant authorities are anti-Enlightenment.

Kant was giving an account of the spirit of the age through which he Minds roused from their lethargy do not simply say yes to authorities. Putting themselves into a fermentation, turning themselves on all sides, and thereby enjoying the privilege of rational creatures these are acts of critiquing authorities, not of mindlessly accepting the word of others.

The foregoing accounts of the spirit of the age suggest that Enlightenment is on the side of modernity and may indeed be what modernity is. I shall offer a brief defence of this claim. Modernity is a distinct kind of attitude to the modern, not just our attitude to the modern of our day but any persons attitude to his modern. What makes the attitude modernist is that the agent observes in a creative way, thinking for himself, and seeing the world as open to change to which he can and should contribute. In that sense modernity implies an attitude of engagement with the world, and a recognition that such engagement is not a moral option but is instead a demand that morality makes on us. As such, modernism implies critique of the present for the sake of a better future. Its target can be anything that is in the agents presence; he can critique institutions, whether of law, politics, religion, education or industry, and so on, and seeks change in response to a moral demand that arises from the critique. Because moral demands flow from these critiques, there is an imperative of modernity, the demand that we improve what it is in our power to improve. Modernity is therefore a reflective and also active participation in the real world, by which the agent aims to inform the future through Montesquieu arguing for the separation of powers in a political state, Adam Smith arguing the case for free trade, Voltaire campaigning for justice for the Calas family, David Hume denouncing superstition and enthusiasm in the field of religion, Rousseau proposing a given form and content for education for children, were all responding to the imperative of modernity their modern being the Age of Enlightenment.