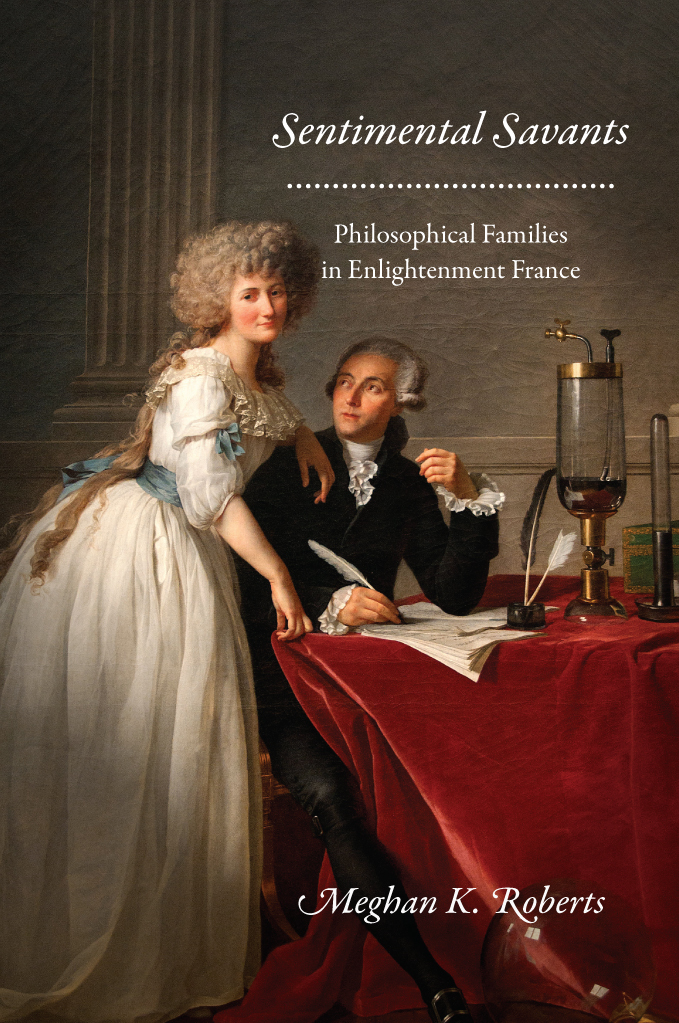

Sentimental Savants

Philosophical Families in Enlightenment France

Meghan K. Roberts

The University of Chicago Press

CHICAGO & LONDON

MEGHAN K. ROBERTS is assistant professor of history at Bowdoin College.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-38411-5 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-38425-2 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226384252.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Roberts, Meghan K., author.

Title: Sentimental savants : philosophical families in Enlightenment France / Meghan K. Roberts.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015042753 | ISBN 9780226384115 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226384252 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: FamiliesFrancePhilosophy. | PhilosophersFamily relationshipsFrance. | EnlightenmentFrance.

Classification: LCC HQ623. R 63 2016 | DDC 306.85dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015042753

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

What did it mean to be a philosopher in the Age of Enlightenment? Was the ideal man of letters, as tradition held, a celibate bachelor married to Philosophy? Or was he a man of the world, married, possibly with children? These questions provoked much hand-wringing during the eighteenth century. Men of letters aspired to be sociable and useful but also wanted to safeguard their independence. Would polite socializing help them communicate with each other and accrue new knowledge? What was the value of undisturbed solitude? If marriage was healthier and more socially useful than celibacy, should anyone sign up for a life of sexless bachelorhood? These questions were, in many ways, old ones: similar debates had flared up during the Renaissance and Reformation. But the savants of the French Enlightenment attacked these questions with zeal, and a significant number decided they could best live their intellectual and social ideals by marrying and fathering children. Many founded families, a move that transformed their work in fundamental ways.

Families, both real and metaphoric, occupied considerable real estate in the cultural landscape of eighteenth-century France. Family metaphors constituted the bedrock of political authority, with the king as father of his people. Novels, many of them coated in a thick gloss of family feeling, became wildly popular. Plays dramatized family stories with bold gestures and copious weeping. Treatises proposed new ways to nurture family emotions, seeing the love between husband and wife, mother and child, father and family as key to social reform. A thriving public sphere remained interwoven with more intimate categories. Stories about individual families functioned as metaphors for social corruption and regeneration, while revolutionaries imagined private life as a font of public virtue and patriotism. Families were everywhere in the print culture of the period, and the philosophes

And yet, for all that historians know about domestic life, for all that scholars have contemplated private life and its public import, few have studied the stories that men of letters told about their own family lives. Why not? The question of married men of letters has attracted little attention from historians in part because they have assumed that conspicuous casesRousseaus abandoned children, Voltaires affairsspeak for all savants. Such examples have encouraged historians to see family life as removed from the work of philosophy. In The Literary Underground of the Old Regime, for example, Robert Darnton suggests that the true philosophe could only be an unmarried man. A philosophes marriage signified his domestication, his capitulation to tradition and conformity. Nor is Darnton the only historian to assume that thinkers cared little for marriage. Only a few scholars, such as Anne Vila, have explored questions related to married savants. Given their focus on one individual, however, biographies are not the best medium for discovering wider trends in Enlightenment culture. When viewed one at a time, married philosophers seem exceptional rather than a part of a larger cultural pattern. And so for most scholars, families have rarely factored into the intellectual histories of the eighteenth century. The myth that family life had little to do with philosophy has persisted.

Sentimental Savants solves this problem of scale by drawing on a number of case studies: the Du Chtelet, Diderot, Helvtius, dEpinay, Condorcet, Necker, Lavoisier, and Lalande families. I am hardly the first scholar to study the likes of these, but my approach connects these famous individuals to their culture in new ways. By examining savants immersed in a diverse array of fields, from chemistry to pedagogy, agronomy to anatomy, I show that shared cultural practices united them. Rather than separating natural philosophers from novelists, women from men, nobles from bourgeois, I look instead at their common traditions and ideals. This is not to deny that real differences existed between my case studies. The savants studied here had varying levels of wealth and social privilege, and I take care to note the ways in which those circumstances shaped their individual experiences.wide appeal of these ideas and practices, I glean evidence from collective sources such as eulogies and biographical compendiums.

Using this mix of sources, I argue that a new intellectual ideal emerged in the eighteenth century. Bachelorhood (if not necessarily celibacy) continued to appeal, but family life also beckoned. How lovely it would be, thought some philosophers, to have a devoted wife and affectionate children. Seduced by visions of domestic bliss and familial collaboration, many men of letters turned away from an ascetic life of bachelorhood and dreamed of other possibilities. A new model captivated them: a brilliant man whose loving wife and devoted children enhanced, rather than distracted from, his intellectual life. Eighteenth-century thinkers had come a long way from the curt dismissal of domesticity issued by the scholastic philosopher Peter Abelard (d. 1142), who had asked: What could there be in common between scholars and wetnurses, writing desks and cradles, books, writing tablets, and distaffs, pens and spindles? Rather than defining the life of the mind as a total retreat from domestic life, married Enlightenment philosophers imagined social bonds and family love as nurturing and supporting their work. Portraying themselves as loving husbands and fathersthe very picture of idealized sentimental masculinityhelped thinkers represent themselves as engaged members of society who provided a virtuous example for the public to follow.

These sentimental savants, as I call them, were interested in more than emotional solace. An exciting new array of empirical possibilities called to them. Married philosophes often had children, and those children offered a tantalizing opportunity for savants to practice an intimate form of empiricism. Education, so vital to Enlightenment thought, need not be an abstract exercise; they could try out the latest theories. Likewise, philosophes who advocated smallpox inoculation did not need to confine their enthusiasm to the pages of their pamphlets. They inoculated their children, generating proof for the public that the technique was indeed safe and effective. Philosophes seasoned their publications with references to these private practices, bolstering their intellectual authority and anchoring their ideas in compelling narratives. They invited other parents to follow their example, to see savants as moral exemplars as well as extraordinary intellects. If more and more families made themselves like philosophes families, they suggested, social reform would take deeper root.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).