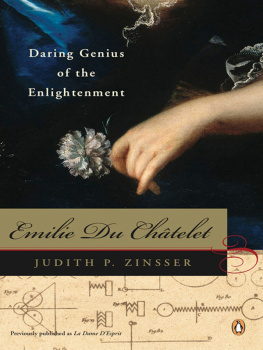

EMILIE DU CHTELET

DARING GENIUS OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT

JUDITH P. ZINSSER

Previously published as La Dame dEsprit

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America as La Dame dEsprit: A Biography of the

Marquise Du Chtelet by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2006

Published in Penguin Books 2007

Copyright Judith P. Zinsser, 2006

All rights reserved

The prologue in different form appeared in Rethinking History, issue of Spring 2003, and later in Experiments in Rethinking History, edited by Alun Munslow and Robert A. Rosenstone (Routledge, 2004).

ISBN: 978-1-1012-0184-8

CIP data available

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

To

Les Introductrices:

Gretel Zinsser Munroe

and

Barbara Lewis Zinsser, Esq.

Prologue: 1749

From the window of the queens apartments at the palace of Lunville in Lorraine, alles of trees shadow the gravel walks, and borders of yellow and red zinnias brighten the vista. Fountains and the series of circular reflecting pools suggest some relief from the late summer heat, particularly in the early hours of the evening. One Saturday at the end of August 1749, Gabrielle Emilie le Tonnelier de Breteuil, marquise Du Chtelet, the forty-two-year-old philosophe , mathematician, and authority on Leibniz, sat at her desk by this window amid the apparent chaos of her scholars tools. All around her, piled on the parquet floor, the bureau, and the shelves of cabinets, were the mathematical and astronomical treatises, the books of physics, and Newtons Principia and his System of the World that she had translated and on which she was now completing a commentary. Bits of paper, sealing wax, a compass, the cup of trimmed quill pens, the ink pot, the shaker of sand littered the desk. Her quarto-sized notebook lay open. She had indicated in the margins the calculations to be corrected. Now page proofs had to be revised, explanations clarified, line after line of complex equations rechecked.

On that August evening, she must have pushed all the papers aside. She found a blank sheet of her stationery with its delicate hand-painted border, folded it in half, and began a letter to Jean-Franois de Saint-Lambert, her young lover and the man responsible for her pregnancy. The summer light may still have been bright enough for her to write by, or perhaps she called to have the candles in the wall sconces and in the holders on the tables lit. Opening the tall casement windows that face the garden would allow for a breeze, but might scatter bits of wax on her papers, and cause the tapers to burn unevenly.

In this letter, thoughts came in no particular order, but turned around her need for her lover to be in the same place as herself. His military duties have kept him in Nancy. She has lived two days without any word from him. She can be patient about her condition when he is with her, but when I have lost you, I see only black. She suggests that her long letter of yesterday will please him more than this one, not because I was loving you better, but because I had more strength to tell you.

Today, she writes, her belly has dropped so low that the pain in my kidneys is unbearable; she will not be surprised if she gives birth tonight. She reports that she walked in the garden, but her fears, the presentiments of death that color this, her fourth pregnancy, are so strong, she feels despondent in both spirit and her whole being. She began to write in smaller letters with less space between the lines, to be sure she could finish her last thought by the end of the page. Only her heart is spared, she continuesby implication, spared in order to love him. The last sentence, in even smaller script, runs along the pale-green border: I finish because I can write no more.1

In less than a week, Mme Du Chtelet completed the revisions of her commentary on Newton, and in the early morning hours of September fourth, she gave birth to the baby, a daughter, Stanislas-Adlade, named for Du Chtelets host and patron, King Stanislas, former king of Poland, and now duc de Lorraine. Despite the ease of the delivery, six days later, on September tenth, she died suddenly of a cause her contemporaries could not identify. The infants baptism, and then her death a year and a half later, were duly recorded in the parish register. Although Du Chtelets husband accepted paternity, it was widely rumored that the child was not his. And what of Du Chtelets translation and commentary, her grand project of the previous five years? It almost died as well, unpublished until 1759ten years after its completion, and long after the authors friends and lovers had moved on to other amusements and other concerns.

This is one possible beginning for the biography of this brilliant, unorthodox woman. But Mme la marquise Du Chtelet can be introduced in a different time and place. In Paris a few months earlier, in May 1749, she was in residence in a grand three-storied house in the rue TraversireSaint Honor. She and Voltaire each had a suite of rooms, or appartement . The htel, as such a house was called in eighteenth-century France, was only a few blocks from the busy government offices of the Louvre, and from the royal palace of the Tuileries. In this second beginning, Du Chtelet also sits at her work, in the middle of writing what will be an eleven-page letter to her young army officer. Although Saint-Lamberts letter has been lost, he must have asked her once again to join him in Lorraine, where he was garrisoned. For in her answer she will both justify their separation and detail the sacrifices she has made in order to complete her grand scholarly project and to rejoin him before the baby arrives. She was in the sixth month of her pregnancy, when a woman usually feels strong and the babys size does not yet cause much discomfort. Contemporaries described her as big-boned, perhaps five feet six inches, taller than many men, and since this was her fourth pregnancy she could expect all to go easily until the last few weeks and the birth itself.