HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is:

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2000

Copyright Magnus Magnusson 2000

The Author asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780006531913

Ebook Edition SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007374113

Version: 2016-03-15

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

From the reviews of Scotland: The Story of a Nation:

The answer to a prayer a history of this complex country that is at the same time intelligent and intelligible

IAIN GALE, Sunday Herald (Glasgow) Books of the Year

Readable, poignant, fascinating, a lively combination of narrative and analysis

The List

[Magnus Magnusson] is excellent on the sense of place in history, and any visitor to Scotland would benefit from taking this book as a companion

ALLAN MASSIE, Spectator

This is never a dry and dusty academic account. [Magnusson] weaves into his narrative a geographical tour of the countrys historical sights that can only come from being a former chairman of Scottish Natural Heritage. His colourful descriptions of historys main players are often filled out with humorous and telling anecdotes of the time The great strength to which Mr Magnusson plays is the richness of characters who set the course of the nations history, from the Roman Agricola through William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, Mary Queen of Scots and John Knox to Rob Roy, Sir Walter Scott and beyond. The book will fill many a dark winter evening for anyone who wants to learn more about Scotlands complex past

LAURA KIBBY, Sunday Express

These Tales were written in the interval of other avocations, for the use of the young relative to whom they are inscribed [Sir Walter Scotts grandson, John Hugh Lockhart]. They embrace at the same time some attempt at a general view of Scottish History, with a selection of its more picturesque and prominent points The compilation, though professing to be only a collection of Tales, or Narratives from the Scottish Chronicles, will nevertheless be found to contain a general view of the History of that country, from the period when it begins to possess general interest.

SIR WALTER SCOTT,

PREFACE TO TALES OF A GRANDFATHER

These are stirring times for Scotland. With a parliament of its own the first for 292 years Scotland stands on the threshold of a new future. What this future will bring is anyones guess; all we can be sure of is that it will be informed and influenced by the past, just as our present has been. History gives the present a context.

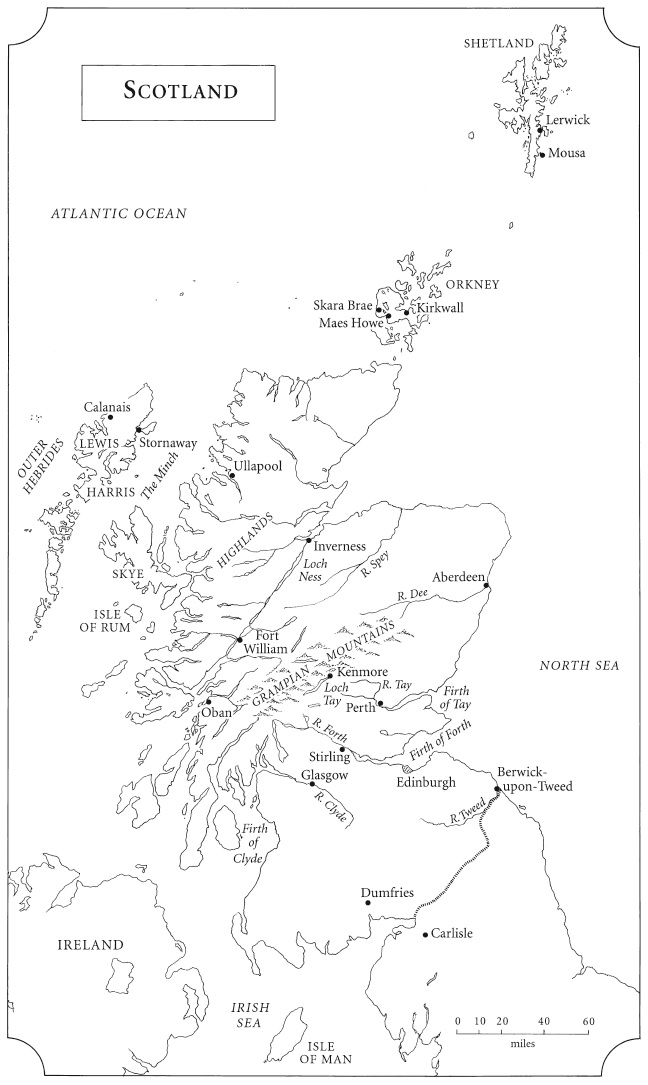

In this book I have tried to tease out the significant strands in Scotlands history which highlight the key concepts of nationhood and identity. When and how did the many peoples who inhabited Scotland become Scots? When and how did the country of Scotland become the nation of Scotland? How did relationships with England (and other nations) evolve? How did an independent realm develop? How did the role of kingship, the concept of monarchy, develop? When and how did the governance of Scotland evolve into the community of counsels which is now called parliament?

All these threads are woven, often luridly, into the tapestry of Scotlands past. But what was that past? The Scottish history which I absorbed in my childhood was the history of Scotland as expressed and cast in the nineteenth century by the greatest novelist of his day, Sir Walter Scott. Some 175 years ago he wrote Tales of a Grandfather (182729), purportedly for the edification of his grandson John Hugh Lockhart, whom he addressed by the neat pseudonym of Master Hugh Littlejohn. In the Tales, Scott told history essentially as story. He was a brilliant teller of history. And he had a wonderful feel for the natural landscape, for the scenes where history happened history on the hoof, one might call it. This is one of the things which have made his Tales such an enduringly popular exposition of history for generations of readers of all ages.

Like every historian, Scott had his own views there is no such thing as truly objective history: every generation writes its own history to suit its own agenda, for history is part of the process of cultural definition and redefinition. Scotts agenda was very clear. Soon after writing the Tales, he expanded his childrens book into a grown-up History of Scotland, 10331788 (published in 1831). His purpose, as he put it, was to show the slow and interrupted progress by which England and Scotland, ostensibly united by the accession of James the First of England, gradually approximated to each other, until the last shades of national difference may be almost said to have disappeared.

Implicit in everything Scott wrote was the assumption that this union of England and Scotland was the inevitable outcome of an inevitable historical process a process which meant progress. He believed passionately that the Union of the Crowns in 1603 and the Union of the Parliaments in 1707 had helped Scotland to mature out of turbulent and rebellious adolescence into adult nationhood, as an equal partner in the corporate nation-state of Britain.

Walter Scott was a meticulous and extremely erudite historian as well as being the first great historical novelist. He was familiar with all the fashionable theories of history of his day. He read extraordinarily widely, had a remarkable memory, and absorbed information from all manner of sources. He searched out medieval manuscripts and founded societies to edit and publish them.so in their effects. And in his greatest novels (where his characters are constantly seen as being helplessly trapped in the social and economic forces of history), no less than in his writing of history, he subtly and imaginatively examined the meaning of history in terms of the relationship between tradition and progress. Scotland, it has often been said, was invented by Walter Scott in his portrayal of its history.

But Scotts version of Scotlands history is now largely out-of-date; and so are the ideas about history which informed it. History is continuously being reassessed and rewritten. That is what Walter Scott was doing he was harnessing the events of the past to reinforce his agenda for his own time: simultaneously conservative and progressive.

In the last few years there has been a revolution in Scottish historical thinking. Many of our cherished conceptions and ideas about our past are being revised. Where did the Scots come from? What happened to the Picts? And what about Macbeth, whom both Shakespeare and Scott cast as the prototype villain of Scottish monarchy? Did Robert Bruce ever see a spider in a cave? How important was the Declaration of Arbroath (which Scott does not even mention)? What was the Scottish Renaissance? What really happened at the Reformation? What was the significance of the reign of Mary Queen of Scots? Who were the Covenanters? What was the impact of Jacobitism on the Highlands and the Scottish identity? And what were the real, long-term effects of the 1707 Treaty of Union?