This eBook edition published in 2012 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Tim Clarkson 2010

First published in 2010 by John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

The moral right of Tim Clarkson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-906566-18-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-907909-02-3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In writing this book I have benefited from advice and assistance given generously by a number of people. To them I express my gratitude for helpful comments and suggestions on specific points, or for providing me with useful information. I wish to particularly thank Hugh Andrew, Stephen Driscoll, Kevin Halloran, Alex Woolf and Michelle Ziegler. Any errors and idiosyncracies in the book are, of course, entirely of my own devising. On the editorial side I am grateful to Mairi Sutherland for her unwavering patience and attentiveness, and to Jackie Henrie for ironing out the crinkles in the narrative. Mark Brennand at Cumbria Historic Environment Service kindly gave permission to reproduce the aerial photographs of Liddel Strength. Other photography is the work of my wife Barbara who took on the additional role of chauffeuse along the highways and byways of Scotland.

TC

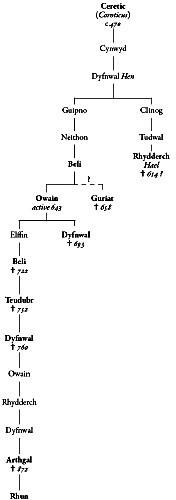

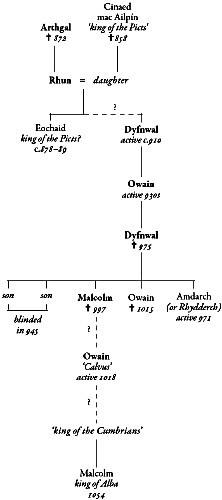

Kings of Alt Clut, fifth to ninth centuries, based on the Harleian pedigree of Rhun ab Arthgal. Names in bold are attested as kings in sources outside the pedigree.

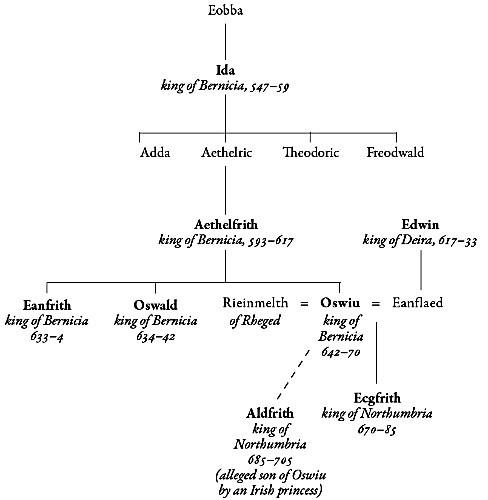

Bernician kings of the sixth and seventh centuries (dates derived from Bede). Some siblings omitted in each generation.

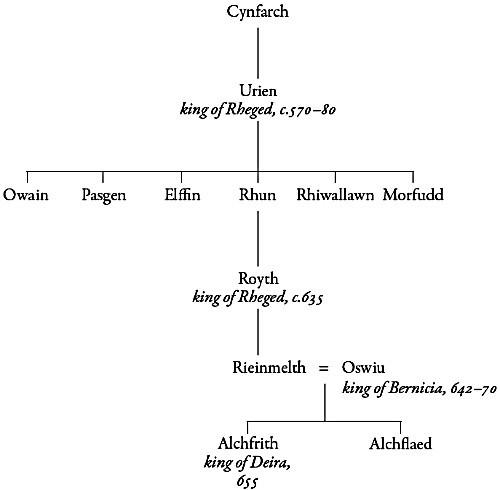

The family of Urien Rheged

Kings of Strathclyde, c.870 to c.1060, shown in bold. Based on a table produced by Dauvit Broun (Broun 2004, 135).

INTRODUCTION

Gwr y Gogledd

The medieval kingdom of Scotland began as a fusion of different peoples, each with their own language and culture, who were brought together during a period of change spanning the ninth to twelfth centuries. Two groups in particular the Scots and the Picts are generally viewed as the most important players in the process, their unification in the mid-ninth century being seen as the beginning of a recognisable Scottish identity. The other main groups were the Scandinavians, the English and the Britons, the latter two inhabiting what are now the Lowlands south of the River Forth. By c.1100 most people living north of the Forth spoke Gaelic, the language of the Scots, even if the speech of their forebears had been Pictish. Their neighbours to the south-east, in Lothian, had become subjects of the Scottish kingdom but many were English-speakers whose ancestors had been ruled by English kings. From the speech of these Lowlanders came the tongue we now call Scots or Scottis , essentially a northern English dialect. The lands west of Lothian were inhabited by a people who spoke neither Gaelic nor English. These were the last remnant of the North Britons, a group whose role in the shaping of Scotland is frequently ignored, forgotten, or overshadowed by the roles played by their neighbours. To their English-speaking contemporaries they were known as wealas , Welsh, and in Latin documents of the time they appear as Cumbrenses , Cumbrians. Their language no longer survives but it was descended from an indigenous tongue, commonly termed Brittonic or Brythonic, that had once been spoken in almost every part of Britain. Brittonic survives today in several evolved forms as the living languages of Wales, Cornwall and Brittany but it ceased to be heard in Scotland 800 or 900 years ago. Its disappearance became inevitable in an age when those who used it faced strong pressure to adopt alternative tongues such as Gaelic and English.

Few traces of the North Britons have survived, hence their often minor presence in our history books. In terms of a general picture of Scottish medieval history they are far less well-known than the Scots, Picts and Vikings. Much of what we know about them comes not from Scotland but from Wales, from a body of literature in which their kings were praised as mighty warlords in a remote heroic age. To a thirteenth-century Welshman these kings of old were his fellow countrymen, members of an ancient British nation to which he himself belonged. In his own language he knew them as Gwr y Gogledd , the Men of the North.

Sources

This book represents one attempt to construct a narrative history of the North Britons. The sources involved in such a construction (or reconstruction) are not especially suited to the task, nor do they sit comfortably under the kind of close academic scrutiny to which they have been justifiably exposed in recent years. In many cases this scrutiny was long overdue. Some sources have indeed failed the strict reliability tests demanded by todays scholarship, usually because they have turned out to be far removed in time and place from the historical events they claim to report. Others pass the tests with certain caveats which mean that they can be used only with caution or in circumstances where no alternative source exists. Casual acceptance of information provided by these texts is no longer an option. All of them invite scepticism and none can be accepted at face value. In the chapters that follow some of the most important sources are discussed individually or in genre-groups. Space considerations and the needs of the narrative mean that no individual source is examined in great detail, although references point to further reading on particular issues. In this introductory section a brief and selective survey is offered as a preliminary overview of the literature.

The main time-period covered by this book falls between c.400 and c.1150. The first half of this span corresponds roughly to an era now termed Early Historic, a time when an indigenous tradition of historical writing began to appear in the British Isles. The foremost ambassador of this tradition was Bede, an English monk who lived in the Northumbrian monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow during the late seventh and early eighth centuries. Bede is usually regarded as a fairly reliable historian, and in certain respects this is probably true, but he was not really a historian by any modern definition. His vision of the world perceived human history as the gradual unfolding of Gods Will with regard to mankind in general and to the English in particular. This perception runs through his best-known work, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People , in which he presented a view of events in his homeland from Roman times through the ensuing centuries to the twilight of his own life in 731. He has much to say of northern Britain, including the parts later to become Scotland, but in the Britons themselves he had little interest. In fact, he frequently regarded them with disdain.