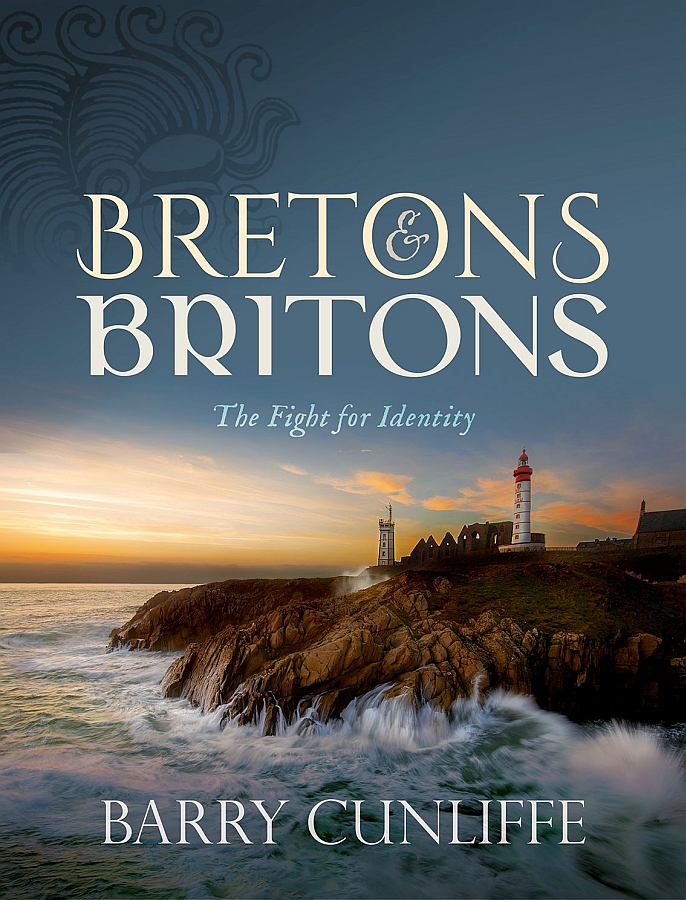

BRETONS & BRITONS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Barry Cunliffe 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other form and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945333

ISBN 9780198851622

ebook ISBN 9780192592477

Typeset by Sparkswww.sparkspublishing.com

Printed in Great Britain by

Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and

for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials

contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

In memory of Pierre-Roland Giot

and for Patrick Galliou

PREFACE

A T one level this book is a simple narrative: a history of Brittany from early prehistoric times to the beginning of the twentieth century. Its real purpose, however, is to explore the fascinating subject of identity: how a people living in a remote peninsula of Europe, to distinguish themselves from their neighbours, created and fought to maintain a distinctive culture. The sea played an important role in protecting them, but it also enabled a close relationship to be built up between the Bretons and the Britons, forming a bond that has developed over the years. Today increasingly large numbers of people travel on Brittany Ferries between the ports of Plymouth and Roscoff and Saint-Malo and Portsmouth to spend time in each others countries, their journeys echoing those that began in prehistoric times and have continued ever since.

While Breton identity and the relationship between Bretons and Britons are the main themes of this narrative, underlying it all is a desire to pay homage to a country and a people I have come to know and admire over the last sixty years. In 1960, when an undergraduate at Cambridge, I attended a lecture given by Pierre-Roland Giot, doyen of Breton archaeology, and later sent him a photograph of a Bronze Age arm-ring of Breton type that had recently been found in west Sussex. It began a correspondence that continued over the years, accompanied by a deluge of offprints of scientific papers that he and his colleagues had published. A few years later, after I took up a post at Southampton University, we became neighbours separated only by the sea, and contact was more frequent. Giot was a generous colleague who loved sharing his country with his friends. In doing so he ensured that Brittany featured large in the European narrative.

Patrick Galliou is another Breton scholar who has always seen Brittany as part of the wider world. We shared interests in the Roman period and it was when we were discussing late Roman coastal defences that he suggested we might co-direct an excavation at the site of Le Yaudet, a fortified promontory at the mouth of the river Lguer occupied in the Late Iron Age and throughout the Roman period. It was evidently a key site in understanding cross-Channel interactions. Excavations began in 1991 and were to last for twelve happy seasons, involving Breton, British, and Spanish students. During this time we were made welcome by the local community, enjoying both their hospitality and their enthusiasm. Those friendships have continued and have grown. Returning now, several times a year, to the little settlement of Pont Roux in the shadow of Le Yaudet is like coming home.

This book, then, is a labour of love written to celebrate the forces that have bound our two countries, and in profound appreciation of the ever-fascinating Breton countryside. Above all, it is a tribute to the remarkable resilience of the Breton people.

B.C.

Oxford and Pont Roux

August 2020

CONTENTS

T HIS book is about the people who have lived on the peninsula we now call Brittany, a slab of land on the edge of Europe jutting into the fierce Atlantic. To the land-bound French the western extremity of the continent has long been known as Finistre, the end of the earth. But to the inhabitants their peninsula was the centre of the world: it was the rest of Europe that was peripheral.

Remote places like peninsulas and islands have a particular fascination because, to distinguish themselves from outsiders, their communities spend much effort in defining and protecting their cultural identity. Islanders find it easier because they are surrounded by the sea, which gives them a degree of control over the acceptance or rejection of external influences, but those who inhabit peninsulas are less fortunate. While the sea offers welcome protection on many approaches, there is always a land border making the territory vulnerable to intrusion. They may try to fortify it, creating a marcher zone, but more often the border is vague and porous, allowing easy access to outsiders. This is why peninsular people have to work hard, not only to safeguard their culture but to intensify their differences with their land neighbours, the better to distinguish themselves from the alien other. As one social anthropologist put it, remote places are the very crucibles of the creation of identity.

The sea is all-important. It provides a barrier to unwanted outside interference while at the same time it allows maritime networks to develop, offering connectivity. By embracing overseas neighbours and becoming part of a broader maritime community peninsula dwellers can further enhance the distinctiveness of their culture in contrast to their continental neighbours. The sea also binds maritime people together. The narrowing strip of the Atlantic which we call the English Channel or La Manche separates the Breton peninsula from the parallel coast of southern Britain, itself ending in a peninsula comprising Devon and Cornwall. The narrowness of the Channel seaway has allowed close contact to develop between communities living along confronting coastlines. These links began to be forged seven thousand years ago and have continued to develop ever since. Many generations of Bretons have looked to their British neighbours as compatriots whose values they shared, while the neighbouring French were considered to be a threat to their culture and their being.

Remote places are, by definition, on the edge of the familiar world. When viewed from the centre, they are distant and peripheral: irrational places where reality fades into fantasy. In the popular imagination Brittany has been seen as a land where ranks of warriors were turned into rows of stone. It was a place of enchanted forests with magic fountains providing a haunt for Druids and later the magician Merlin of the Arthurian romances: it was a twilight zone where anything was possible. Remote islands, too, were steeped in mystery. The Greek writer Strabo described several islands off the coast of Brittany where strange rites were enacted, and when some Roman soldiers were shipwrecked on the British shore sometime before the Roman occupation of the island, they reported monsters, half-man and half-beast, lurking in the persistent mists. These far-western fragments of land, washed by the ocean, were in the thrall of irrational powers and their magic.

Next page