CONTENTS

A book of this kind would not be possible without the contribution of many people. I would like to thank all those who have shared their ideas on Iron Age and Roman East Yorkshire with me, particularly Lindsay Allason-Jones, John Collis, John Creighton, Peter Crew, John Dent, Peter Didsbury, Melanie Giles, Ian Armit, Ian Haynes, Martin Henig, Yvonne Inall, Jim Innes, Rod Mackey, Peter Makey, Terry Manby, Martin Millett (my collaborator in the Foulness Valley project), Tom Moore, Patrick Ottaway, Mark Pearce, Rachel Pope, Jenny Price, Dominic Powlesland, Steve Roskams, Steve Sherlock, Bryan Sitch, Ian Stead, Jeremy Taylor, Steve Willis and Pete Wilson. I am grateful to many past and present students from the University of Hull, especially those who undertook research in the territory of the Parisi; their work is acknowledged in the text and bibliography, and also my archaeological colleagues there, Helen Fenwick and Malcolm Lillie.

I am very grateful to all those members of ERAS and YAS and CBA Yorkshire who have participated in fieldwork and listened to reports on work at various stages. I would like to thanks Dave Evans, Ruth Atkinson, Trevor Brigham and Ken Steedman from Humber Archaeology Partnership and the North Yorkshire Historic Environment Record and to John Oxley, York City Archaeologist, for supplying much data and information. Paula Gentil and Caroline Rhodes of Hull Museums allowed access to finds for photography and research and generously gave of their time. David Marchant of the East Riding Museums Service and Andrew Morrison of the Yorkshire Museum also kindly supplied access to finds and other information. Ann Clark and Malcolm Barnard of Malton Museum were very helpful in allowing access to finds. Jody Joy kindly supplied images from the British Museum and valued comment.

Special thanks must go to John Deverell and Mark Norman who helped me compile the database behind the distribution maps, putting in much work. Naomi Sewpaul, John Dent and Pete Wilson kindly read and commented on the text. Big thanks go to Mike Park, photographer at Hull University, who has provided some stunning images, and to Tom Sparrow and Helen Woodhouse for spending a great deal of time and effort on maps and other drawings for which The Marc Fitch Fund kindly provided some funding.

The book benefitted from several periods of research leave provided by the History Department and Faculty of Arts, University of Hull. I am very grateful to the various editors from The History Press, particularly Emily Locke, Ruth Boyes and Glad Stockdale, who have been very patient and helpful. Finally many thanks to my family for all their support during the writing of this book.

Figures and plates are acknowledged in the captions. Figures 2, 8, 9, 11, 15, 24, 32, 34, 49, 56, 71, 77, 79, 84 and Plate 17 are crown copyright/database right 2013. An Ordnance Survey/EDINA supplied service, for the background topographical data.

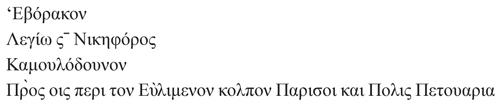

Eboracon (Eboracum)

Legio VI Victrix (Victorious)

Camulodunum

Near a bay (gulf) suitable for a harbour (are) the Parisoi and the town (city) Petuaria.

Ptolemy Geographia 2.3.17.

(Stckelberger and Grahoff 2006, 154; Rivet and Smith 1979, 142.)

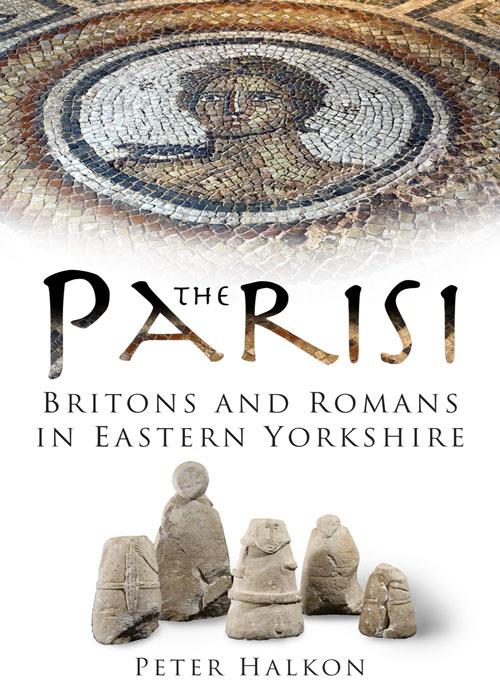

This is the first surviving reference to the Parisi. It was made by the ancient geographer Claudius Ptolemaeus, or Ptolemy as he is better known, who was working in Alexandria, Egypt, during the AD 140s.Writing in Greek, Ptolemy aimed to provide a description of the world as he knew it at the height of the Roman Empire. His account gives the names of its peoples and significant places in their territories across the Roman Empire and its fringes, listing the major features along coastlines such as gulfs, estuaries and promontories and their geographical position as closely as he could (Strang 1997). Like so many ancient texts, Ptolemys original no longer exists, and the book was handed down through various transcriptions, one of the oldest surviving versions dating from the late thirteenth century AD preserved in the Satay Library of the Topkapi palace in Istanbul, which was used in the most recent full translation into German (Stckelberger and Grahoff 2006). Ptolemys account became better known through various Latin versions, hence the use here of Parisi rather than Parisoi.

There are various meanings given for the word itself which is of Celtic origin: the rulers or the efficacious ones, derived from paro , the people of the cauldron which comes from pario cauldron or the spear people, relating to the Welsh par meaning spear (Falileyev 2007, 164).

Ptolemy places the Parisi in what is now eastern Yorkshire. The last definition is particularly interesting as this region possesses an Iron Age burial ritual which involves the throwing of spears at bodies in graves (Stead 1991) which will be discussed in more detail in later chapters.

It is generally presumed, largely due to their geographical coincidence, that there is a direct relationship between Ptolemys Parisi and the earlier Iron Age people whose burials were placed under low mounds surrounded by small square ditches or square barrows, as the densest concentration of these features in Britain is also in this region (Stead 1979; Cunliffe 2005). Although Stead identified the Parisi with square barrows in his La Tne cultures of eastern Yorkshire (Stead 1965), he was more circumspect about this and any connection with the Parisii of Gaul mentioned by Julius Caesar ( Gallic Wars 6:3) in his later books (Stead 1979; 1991).The dead in some of these monuments were accompanied by the remains of two-wheeled vehicles which are usually referred to as chariot burials, and again these are at their densest in East Yorkshire. The first reported excavation of a chariot burial was at Arras near Market Weighton 181517 (Stead 1979), hence the Arras culture, a label attached to these people by the archaeologist V.G. Childe (1940) because of the distinctive nature of their material remains and its restricted distribution (Fig. 1). It was presumed by a number of scholars such as Hawkes (1960) that the culture was brought in to eastern Yorkshire through an invasion from the Marne region of northern France because of the similarity between the burials in both areas, and the discovery of artefacts decorated in a style which takes its name from a middle Iron Age site at La Tne in Switzerland.

According to Hawkes (1960) this incursion followed an earlier Iron Age invasion from the European continent in the so-called Hallstatt period, named after the lake-side village in Austria associated with salt-mining, where a large cemetery with burials containing artefacts decorated in distinctive styles was excavated. The excavations by the German archaeologist Bersu (1940) on an Iron Age settlement at Little Woodbury in Wiltshire demonstrated continuity with the indigenous Bronze Age material culture, rather than continental invasion, based on the shape of houses, which were round in Britain as opposed to their mainly rectangular counterparts on the European mainland, and other aspects of material culture. When Hodson was writing in 1964, insufficient excavation had been undertaken to match square barrows to roundhouses until Brewster (1980) and Dent (1982, 456) encountered them both at Garton-Wetwang Slack. Despite this Hodson (1964) still saw the Arras culture as originating on the continent along with the Aylesford culture of south-east England.