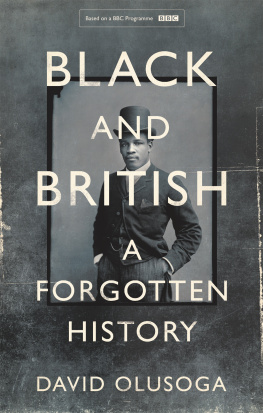

DAVID OLUSOGA

BLACK AND BRITISH

A FORGOTTEN HISTORY

MACMILLAN

Dedicated to the Memory of

Adesola Oladipupo Olusoga

&

Isaiah Gabriel Temidayo Olusoga

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

When I was a child, growing up on a council estate in the North-East of England, I imbibed enough of the background racial tensions of the late 1970s and 1980s to feel profoundly unwelcome in Britain. My right, not just to regard myself as a British citizen, but even to be in Britain seemed contested. Despite our mothers careful protection, the tenor of our times seeped through the concrete walls into our home and into my mind and my siblings. Secretly I harboured fears that as part of the group identified by chanting neo-Nazis, hostile neighbours and even television comedians as them we might be sent back. This, in our case, presumably meant back to Nigeria, a country of which I had only infant memories, and a land upon which my youngest siblings had never set foot.

At the zenith of its swaggering confidence, the National Front the NF made enough noise and sparked enough debate within Britain to make the idea of sending them back seem vaguely plausible. The fact that in the 1970s and 1980s reputable, mainstream politicians openly discussed programmes for voluntary assisted repatriation that were aimed exclusively at non-white immigrants demonstrates the extent to which the political aether had been polluted by the politics of hate. In the year of my birth the Conservative Partys General Election Manifesto contained a pledge to new commonwealth might be happier outside of the UK, and proposed a new British Nationality Act to redefine what British citizenship meant. In my childish fearfulness such discussions translated into a deep but unspoken anxiety that a process might, feasibly, be set in train that could lead to the separation and destruction of my family.

To thousands of younger black and mixed-race Britons who, thankfully, cannot remember those decades, the racism of the 1970s and 1980s and the insecurities it bred in the minds of black people are But they are powerful memories for my generation. I was eight years old when the BBC finally cancelled The Black & White Minstrel Show. I have memories of my mother rushing across our living room to change television channels (in the days before remote controls) to avoid her mixed-race children being confronted by grotesque caricatures of themselves on prime-time television. I was seventeen when the last of the touring blackface minstrel shows finally disappeared, having clung on for a decade performing in fading ballrooms on the decaying piers of Britains seaside towns. I grew up in a Britain in which there were pictures of golliwogs on jam jars and golliwog dolls alongside the teddy bears in the toy shop windows. One of the worst moments of my unhappy schooling was when, during the run-up to a 1970s Christmas, we were allowed to bring in our favourite toys. The girl who innocently brought her golliwog doll into our classroom plunged me into a day of humiliation and pain that I still find hard to recall, decades later. When, in recent years, I have been assured that such dolls, and the words golliwog and wog, are in fact harmless and that opposition to them is a symptom of rampant political correctness, I recall another incident. It is difficult to regard a word as benign when it has been scrawled onto a note, wrapped around a brick and thrown through ones living-room window in the dead of night, as happened to my family when I was a boy of fourteen. That scribbled note reiterated the demand that me and my siblings be sent back.

In the early twenty-first century, politicians in Whitehall and researchers in think tanks fret about the failures of ethnic-minority communities to properly integrate into British society. In my childhood the resistance seemed, to me at least, to come from the opposite direction. Many non-white people felt that while it was possible to be in Britain it was much harder to be of Britain. They felt marked out and unwanted whenever they left the confines of family or community. It was a place and a time in which black meant other, and black was unquestionably the opposite of British. The phrase Black British, with which we are so familiar today, was little heard in those years. In the minds of some it spoke of an impossible duality. In the face of such hostility many black British people, and their white and mixed-race family members, slipped into a siege mentality, a state of mind from which it has been difficult to entirely escape. What drove us deeper into that citadel of self-reliance and watchful mistrust was not just racial prejudice but a wave of racial violence.

Almost every black or mixed-race person of my generation has a story of racial violence to tell. These stories range from humiliation to hospitalization. They are raw, visceral, highly personal and rarely shared beyond family circles. This oral history of twentieth-century racial violence has never been collected or collated, but it is there and it is shocking. Racial violence impacted most dramatically upon me and my family in the mid-1980s, when I was in my early teens. In 1984 my family my mother, two sisters, younger brother and grandmother were driven out of our home by a sustained campaign of almost nightly attacks. For what seemed like many months, but was in fact only a few weeks, we lived in darkness, as the windows of our home were broken one by one, smashed by bricks and rocks thrown from an old cemetery just across the street. As replacing the glass merely invited further attacks the windows were boarded up and we slowly disappeared into the gloom, quarantined together behind a screen of plywood. As the attacks came after dark, policemen working on a rota were dispatched to take up positions behind our front door, in the hope of catching our assailants in the act. When, after a week or so, this plan failed, no other strategy was put forward, and the barrage continued. The bricks bounced off the plywood screens with thuds that left me and my siblings shaking and screaming in our beds.

When the attacks became known at my school I was sat down one afternoon by a well-meaning but inexcusably naive teacher, who recounted to me what was evidently one of his favoured anecdotes. He told me how in the 1960s Louis Armstrong had overheard a white diner, a few tables away in a restaurant, loudly rebuking the waiters for allowing a negro to eat in an establishment that served whites. At the end of his dinner, after he had presumably been mollified by the waiters, the white diner demanded his bill and was shocked to discover that it had already been paid by Armstrong. The meaning of the parable, I was informed, is that by rising above racial hatred Armstrong had won a sort of moral victory. That my teacher believed that this hackneyed yarn, of questionable provenance, was of some relevance to an embattled, angry mixed-race teenager, whose family were under regular attack, was to me even at that age a clear signal that we were on our own.

On a summers evening many months later, long after my family had been delivered from our tormentors and evacuated to emergency housing, I timorously ventured back to our former home after school. I stood across the street, never finding the courage to go any closer. Constantly and instinctively I kept turning my head towards the graveyard from which the bricks and stones had come.

The windows of our former home remained boarded up, as they had been on the day we had hastily loaded up our possessions into a removal van. But a black-gloss swastika had been painted on the white front door. Thick tendrils of paint had dripped down from each arm of that horrible cross. Above and below it had been scrawled the words NF Won Here. If, at that moment I had had the means to leave Britain I would have done so, immediately and with the intention of never returning. Thankfully, I was young, penniless and had nowhere to go. I stayed and life got slowly better.