Padraic X. Scanlan - Slave Empire: How Slavery Built Modern Britain

Here you can read online Padraic X. Scanlan - Slave Empire: How Slavery Built Modern Britain full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London, year: 2020, publisher: Robinson, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

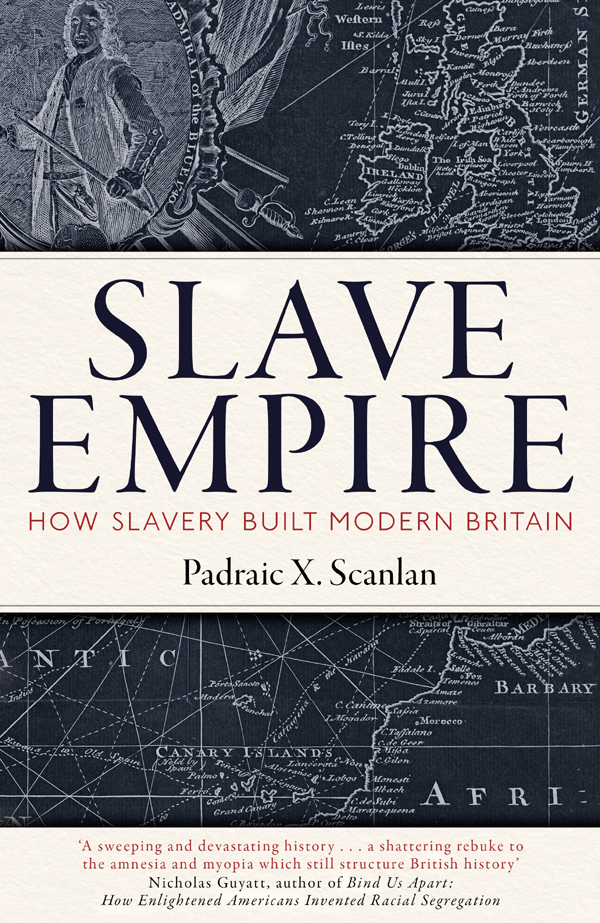

- Book:Slave Empire: How Slavery Built Modern Britain

- Author:

- Publisher:Robinson

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- City:London

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Slave Empire: How Slavery Built Modern Britain: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Slave Empire: How Slavery Built Modern Britain" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Path-breaking . . . a major rewriting of history

Mihir Bose, Irish Times

Slave Empire is lucid, elegant and forensic. It deals with appalling horrors in cool and convincing prose.

The Economist

A sweeping and devastating history of how slavery made modern Britain, and destroyed so much else . . . a shattering rebuke to the amnesia and myopia which still structure British history

Nicholas Guyatt, author of Bind Us Apart: How Enlightened Americans Invented Racial Segregation

Scanlan shows that the liberal empire of the nineteenth century was the outcome of the long encounter of antislavery and economic expansion founded on enslaved or unfree labour. Antislavery was itself the excuse for empire

Emma Rothschild, Jeremy and Jane Knowles Professor of History, Harvard University

Fresh and fascinating, a stunning narrative that shows how an empire built on slavery became an empire sustained and expanded by antislavery. . . deftly combines rich storytelling with vivid details and deep scholarship

Bronwen Everill, author of Not Made By Slaves: Ethical Capitalism in the Age of Abolition

This accessible synthesis of recent scholarship comes at the right time to help shape current debates about Britain and slavery

Nicholas Draper, author of The Price of Emancipation: Slave-Ownership, Compensation and British Society at the End of Slavery

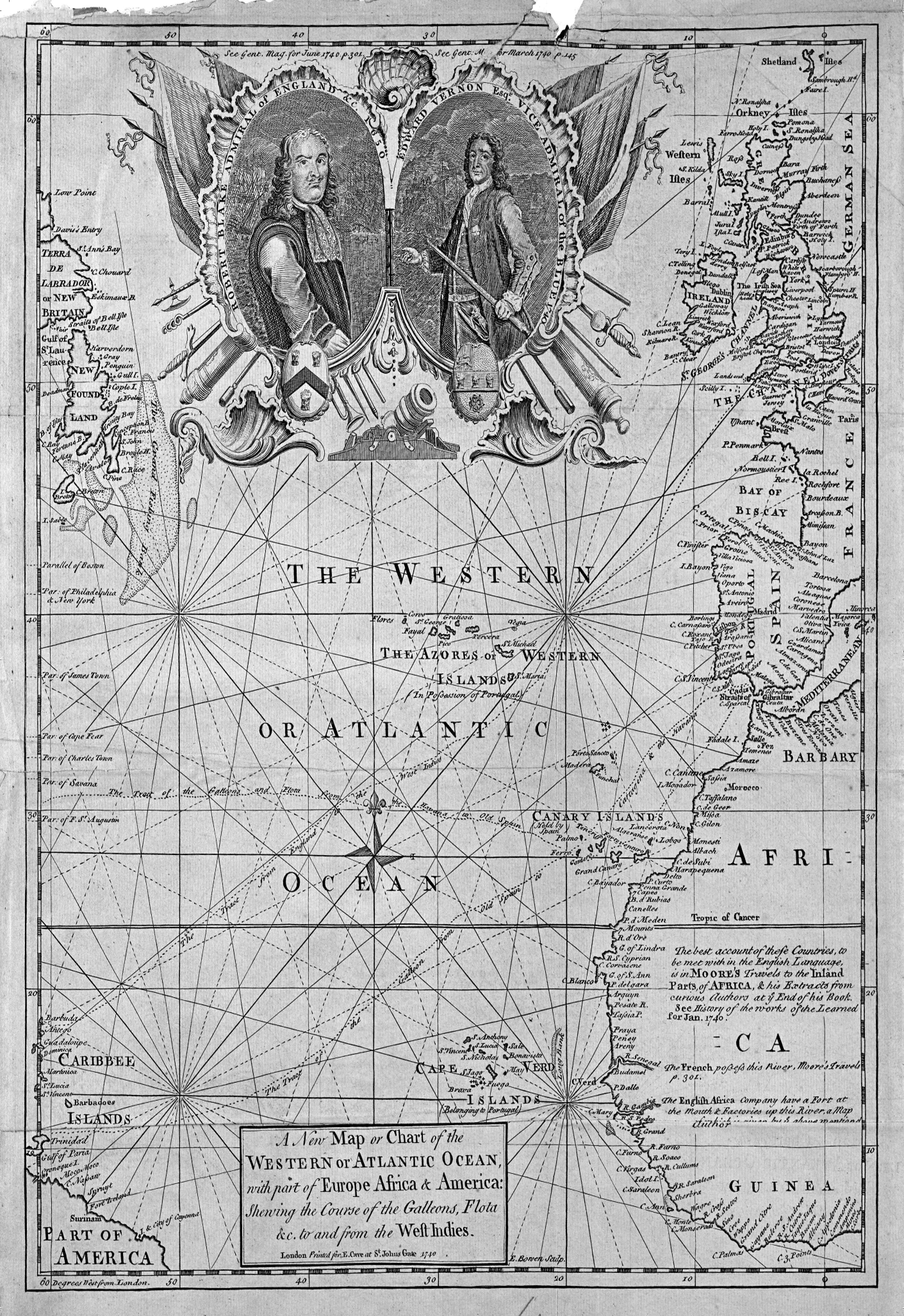

The British empire, in sentimental myth, was more free, more just and more fair than its rivals. But this claim that the British empire was free and that, for all its flaws, it promised liberty to all its subjects was never true. The British empire was built on slavery.

Slave Empire puts enslaved people at the centre the British empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In intimate, human detail, the chapters show how British imperial power and industrial capitalism were inextricable from plantation slavery. With vivid original research and careful synthesis of innovative historical scholarship, Slave Empire shows that British freedom and British slavery were made together.

In the nineteenth century, Britain abolished its slave trade, and then slavery in its colonial empire. Because Britain was the first European power to abolish slavery, many Victorian Britons believed theirs was a liberal empire, promoting universal freedom and civilisation. And yet, the shape of British liberty itself was shaped by the labour of enslaved African workers. There was no bright line between British imperial exploitation and the civilisation that the empire promised to its subjects. Nineteenth-century liberals were blind to the ways more than two centuries of colonial slavery twisted the roots of British liberty.

Freedom - free elections, free labour, free trade - were watchwords in the Victorian era, but the empire was still sustained by the labour of enslaved people, in the United States, Cuba and elsewhere. Modern Britain has inherited the legacies and contradictions of a liberal empire built on slavery. Modern capitalism and liberalism emphasise freedom - for individuals and for markets - but are built on human bondage.

Padraic X. Scanlan: author's other books

Who wrote Slave Empire: How Slavery Built Modern Britain? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.