Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

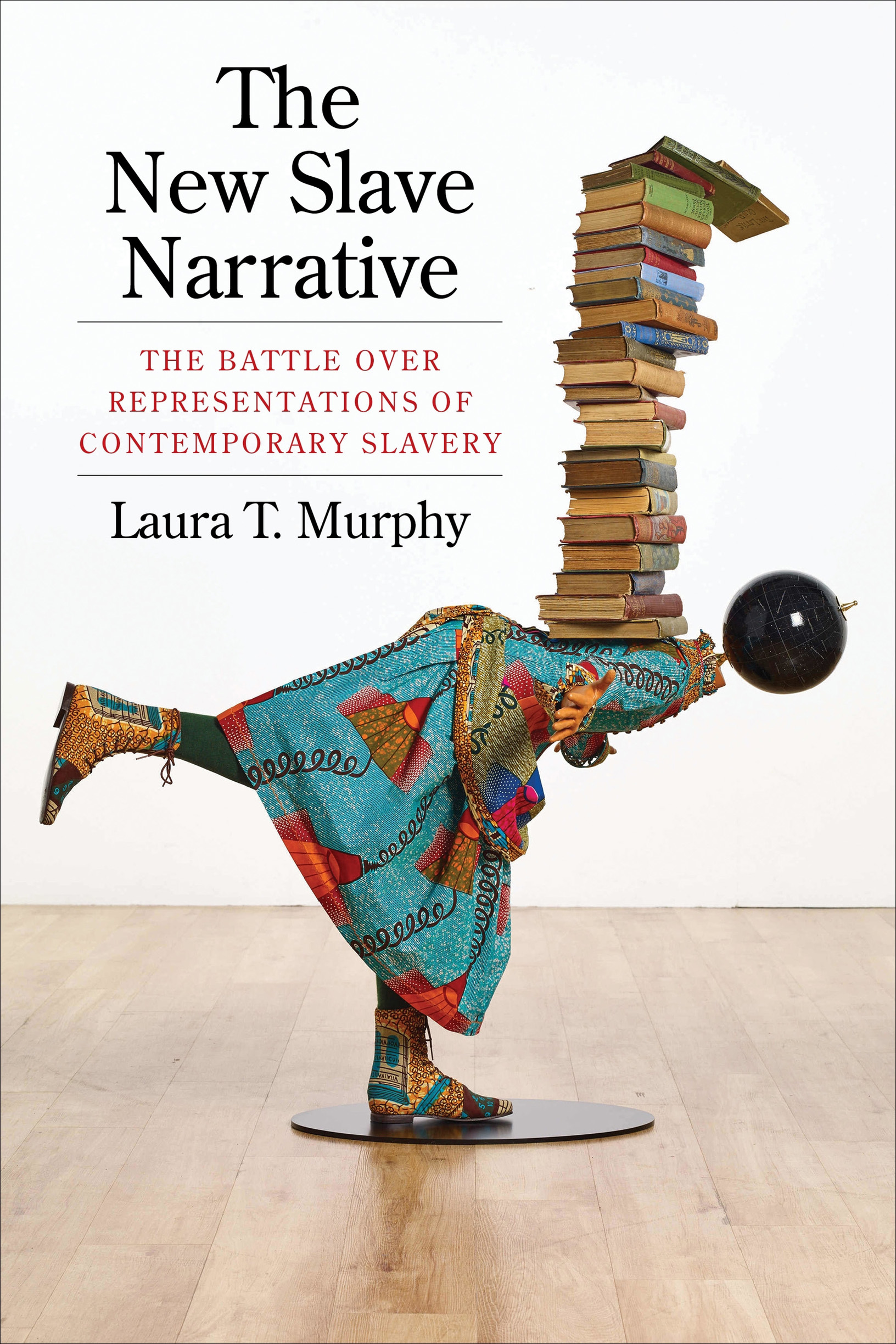

THE NEW SLAVE NARRATIVE

The New Slave Narrative

THE BATTLE OVER REPRESENTATIONS OF CONTEMPORARY SLAVERY

Laura T. Murphy

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54773-4

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-231-18824-1 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-18825-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

LCCN 2019002799

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover art: Yinka Shonibare CBE, Girl Balancing Knowledge III, 2017. Yinka Shonibare CBE. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2019. Image courtesy James Cohan Gallery. Photo: Stephen White.

CONTENTS

My most humble gratitude goes first, of course, to the thousands of survivors of contemporary forms of slavery around the world who have courageously shared their narratives in the hopes that many millions of others will not have to. Special thanks go to Minh Dang, Shamere McKenzie, and James Kofi Annan as well as several other less public survivor-activists whose stories are not included in this book but who have been generous and engaging interlocutors as I have worked on this issue.

I am enormously grateful that the writing of this book was supported by research leaves that bookended its creationthe first words creeped across a blank screen during a pretenure research leave funded by Loyola University New Orleans, and the first draft of the manuscript was then completed on sabbatical while I was the John G. Medlin Jr. Fellow at the National Humanities Center. Final revisions were completed while on a British Academy Visiting Fellowship at the Rights Lab at the University of Nottingham. In between those critical moments of intense reflection, Loyola generously provided me with research funding through the Carter, Bobet, and Marquette faculty research grants.

Any book is the distillation of a thousand excellent conversations. I have many people to thank for those engaging exchanges, which were just as likely to happen on a conference panel as over lunch, coffee, or drinks. Thanks to my Africanist colleagues who have been discussing these ideas with me for a decade now: Ato Quayson, Steph Newell, Gaurav Desai, Adeleke Adeeko, Esther deBruijn, Dan Magaziner, Pallavi Rastogi, Matt Brown, Teju Olaniyan, Matt Omelsky, Ainehi Edoro, Kirk Sides, Madhu Krishnan, Cajetan Iheka, Carli Coetzee, Jacob Dlamini, Luise White, and all the participants of the Bloods Lab at Princeton. I appreciate the sometimes heated but always generative debates I have with my slavery and human rights studies colleaguesKevin Bales, Zoe Trodd, alix lutnick, Melissa Gira Grant, Joel Quirk, Joey Slaughter, Eleni Coundouriotis, Elizabeth Goldberg, Alexandra Schulthies Moore, and Jim Stewart. At the National Humanities Center, I spent many lunches sorting through these ideas with an incredible interdisciplinary group of scholars. Special thanks to Nancy Hirschmann, Harleen Singh, Andrea Williams, Hollis Robbins, Tera Hunter, Libby Otto, Kimberly Jannarone, Tsitsi Jaji, Emily Levine, Jose Amador, Todd Ochoa, David Cory, and the Nineteenth-Century Working Group, each of whom helped add nuance to this project. Many other great scholars, colleagues, and friends have contributed to the conversation; thanks to Carol Ann MacGregor, Julia Lee, Erin Dwyer, Andy Lewis, Lelia Gowland, and Jason Allen.

At Loyola, I am grateful to all my colleagues in the English Department, especially those who have responded to this work: Hillary Eklund, Christopher Schaberg, Tim Welsh, Kate Adams, John Biguenet, Danny Mintz, and Sarah Allison. Ashley Howard pored over the near-final drafts of most of these chapters even when her hands were super full. My brilliant research assistants at LoyolaAmelie Daigle, Jasmine Jackson, Lauren Stroh, and Marley Duethave spent the last few years reading new slave narratives and providing feedback on my ideas, as have the students in my Twenty-First-Century Slavery and Abolition and Slave Narratives, Past and Present courses. My sincere thanks go to Provost Maria Calzada and John Biguenet for supporting this work without fail.

I have presented sections of this book at events at Yale University, the University of Toronto, Kwara State University, Eichsttt-Ingolstadt University, University College London, the University of Wisconsin, Princeton University, the University of Oklahoma, Tulane University, the University of Nevada Las Vegas, Louisiana State University, Lehigh University, Tougaloo University, Rockhurst University, Simpson College, College of the Holy Cross, and the University of New Orleans. The ideas were put to the test at the Bloods Lab hosted by Carli Coetzee and Jacob Dlamini at Princeton University and at the Slavery, Memory, and Literature symposium hosted by Mads Anders Baggesgaard, Madeleine Dobie, and Karen-Margrethe Simonsen at LEcole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales. Thanks to those who invited me and to their generous colleagues and students who asked the difficult questions that were instrumental in developing my thinking on this project.

Thanks to the anonymous reviewer of my earlier collection of new slave narratives, who recommended writing a full critical study of the genre, as well as to the generous anonymous reviewers of this book, whose challenges and provocations were enormously helpful in sharpening my arguments. My gratitude also goes to my editor, Philip Leventhal, for believing in this project and for his tremendously useful advice in the final revisions. Thanks to Abby Graves for her keen and sensitive copyediting and to Ina Gravitz for an index that helped me see my own ideas anew.

To my extraordinary krewe in New Orleansthe Howangs, the Peterae, the Larklunds, CAM, Jerry, and the Birdsyou are my family and constant companions in all things worth doing. And to Rian Thum, my eternal thanks; every page here is marked by your tireless, in-house collegiality.

Sections of was previously published in the Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Inquiry. They are reprinted here with permission.

While almost no one today would argue that forced labor does not exist in the global economy, scholars and advocates are engaged in fierce debates regarding the language we use to describe it. It is important from the outset to explain the choice of some terms that will appear in this book.

Some scholars protest that the word slavery, as it describes contemporary forms of forced labor, is being utilized out of context, without precision, and in ignorance of the gravity of the experiences of people who were enslaved in the antebellum United States. Critics often stress that use of the term slavery outside the fifteenth-to-nineteenth-century transatlantic context (and often, even more narrowly, outside the African American context) insensitively risks diminishing the experiences and legacy of transatlantic slavery. For these critics, the word slavery has been inextricably sedimented in a particular moment and in the particular form of legalized and racialized chattel slavery of the antebellum United States in much the same way the word holocaust, though it predates World War II, is now largely understood as synonymous with the Holocaust in Germany in the 1940s. I contend that these critiques disregard the fact that slavery has taken many forms throughout human history and that it both pre-dates and postdates the very aptly described peculiar institutions of chattel slavery that existed in the Americas.