Contents

Page List

Guide

PRAISE FOR

Freedomville

A powerful, damning account of economic growth, beautifully told through the tragic story of the fight for freedom from slavery of tribals in India. A must-read for anyone wanting to understand modern slavery, the fragility of ideas of freedom, the place of violence in bringing about progressive change, and modern India.

ALPA SHAH,

professor of anthropology, London School of Economics, author of Nightmarch: Among Indias Revolutionary Guerrillas

In Freedomville, Laura Murphy returns to an Indian village known to many as an anti-slavery success story, where she uncovers complex interconnections, unresolved truths, and a community and its former enslavers wrestling with mechanization, globalization, and environmental racism. Drawing on her deep understanding of historical slave resistance and modern human trafficking policy, Murphy echoes Dr. Martin Luther Kings warning that Emancipation cannot become an uncashed promissory note, but must be an ongoing guarantee of liberty and opportunity.

AMBASSADOR (RET.) LUIS C.DEBACA,

Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, Yale University

A brave and brilliant report on the tyranny of the caste system and continuing feudal practices in Indias villages. Freedomville rips apart the cliche of India being the largest democracy in the world and shows us how millions of Indians are deprived of their basic constitutional freedoms and rights.

BASHARAT PEER,

author of A Question of Order: India, Turkey, and the Return of Strongmen, contributing writer for the New York Times

Laura Murphy brings a formidable array of experiences and skills to this compelling project. Trained in literary studies and the author of previous works on slave narratives of the past and human rights abuses in the present, she makes effective use in Freedomville of research techniques associated with oral history, ethnography, and investigative journalism while demonstrating a novelists feel for scene setting, character development, and pacing.

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM,

Chancellors Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine, author of Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink

Freedomville

The Story of a 21st-Century Slave Revolt

Freedomville

The Story of a 21st-Century Slave Revolt

Laura T. Murphy

COLUMBIA GLOBAL REPORTS

NEW YORK

Freedomville

The Story of a 21st-Century Slave Revolt

Copyright 2021 by Laura T. Murphy

All rights reserved

Published by Columbia Global Reports

91 Claremont Avenue, Suite 515

New York, NY 10027

globalreports.columbia.edu

facebook.com/columbiaglobalreports

@columbiaGR

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Murphy, Laura (Laura T.), author.

Title: Freedomville : the story of a 21st-century slave revolt / Laura T. Murphy.

Description: [New York] : [Columbia Global Reports], [2021] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020040310 (print) | LCCN 2020040311 (ebook) | ISBN 9781734420746 (paperback) | ISBN 9781734420753 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Slave insurrections--India--Uttar Pradesh. | Miners--India--Uttar Pradesh.

Classification: LCC HT1249.U88 M87 2021 (print) | LCC HT1249.U88 (ebook) | DDC 306.3/620954/2--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040310

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040311

Book design by Strick&Williams

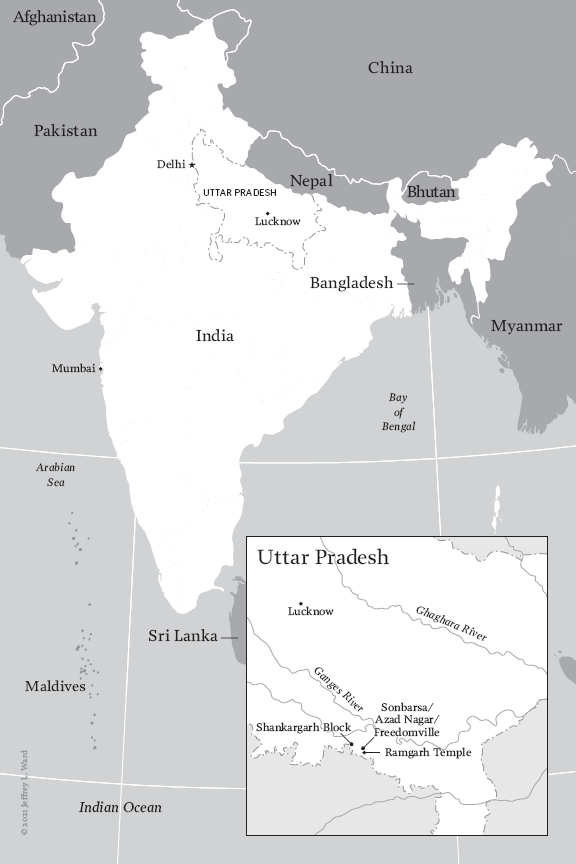

Map design by Jeffrey L. Ward

Author photograph by Cheryl Gerber

Printed in the United States of America

for Kanchuki

CONTENTS

Chapter One

Bound by History and Debt

Chapter Two

Gossip Organizing

Chapter Three

The Fight for Freedomville

Chapter Four

Precarious Freedom

Chapter Five

The NGOification of Revolution

Chapter Six

All Politics Are Local

Chapter Seven

Rock Crushers and the Infrastructure of a New India

Introduction

In a tiny rural village about an hour outside of Varanasi, a woman operates what is essentially the Indian equivalent to a station on the underground railroad, that collection of unmarked safe havens that enabled enslaved people to make their way to freedom in the United States in the nineteenth century. I wont tell you where, but I hide runaways here, the diminutive great-grandmother said.

Weary men who traveled across the state of Uttar Pradesh to escape slavery would seek shelter here. Some of the men had been working in brick kilns, where they found themselves indebted to their employers. As their debts inexplicably grew, their employers expected them to work without being paid more than a bit of grain to fuel their next days labor, and many expected their children to do the same, sometimes even for several generations. Others fled across several provinces to arrive here. Many migrant workers had traveled to big cities for better opportunities, but found forced, unpaid labor in construction or other industries instead. When they tried to quit their jobs, their employers responded with violence or threats. The police often defended the employers.

On the rare occasions that they did run, if they found their way to this village, the woman kept them hidden until she could guide them to the next hideout. A few nonprofit organizers knew she ran a safehouse, and they quietly assisted her. When the police suspected she might be hiding someone, they lurked around the village and harassed her. But she was unshaken. She had been a bonded laborer herself, and she once believed that she would never be able to escape the clutches of the family that had enslaved her own for generations.

People often forget how anonymous the African American abolitionist Harriet Tubman kept herself in order to act as an effective conductor of the underground railroad. Today, Tubman is the subject of biographies, childrens books, songs, and a whole abolitionist imaginary. However, if her contemporaries had known too much about herher name, where she lived, where she worked, who she ferried, what routes she traversed with fugitives in towshe would have lost her ability to help people escape to freedom. Yet she was only one of possibly hundreds who conspired across thousands of miles to provide routes to freedom for enslaved people in the American South, all of whose identities were studiously well-kept secrets. This is one of the great achievements and mysteries of the underground railroad. So, when I heard this womans story, which she shared to enlist the help of the community organizers with whom I was traveling, I quickly deleted her name from my notes. To ensure her ability to continue her work, her story must remain only whispers.

Many people have only recently come to realize that slavery still exists. The Global Slavery Index estimates that . Slavery today comes in many different guises. Haratin people enslaved in Mauritania endure a kind of chattel slavery that eerily resembles the inherited, transgenerational ownership of human lives and labor that characterized plantation slavery in the United States. But most slavery today is less a matter of ownership than it is of inescapable and unpaid forced labor, as it has been in many of its iterations throughout history. Southeast Asian migrants are kidnapped and held captive on fishing boats for years at a time, and often their only escape is death at sea. Chronically unemployed women in Albania are recruited to be nannies in the households of rich Europeans but are surreptitiously trafficked against their will in the sex industry. Young boys and girls in Congo are initiated into the violence of civil war when they are illegally conscripted into armed militias. Even in my hometown of New Orleans, immigrant laborers were held captive and forced to work without pay in the reconstruction efforts after Hurricane Katrina. In the last two years, Uyghurs and Kazakhs have been increasingly compelled to make sports apparel and other cheap textiles and electronics bound for Western markets in extrajudicial internment camps in China in the northwestern region of Xinjiang. What defines these varied experiences as slavery is the largely inescapable forced labor that all of these people endure.