Christian Slavery

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series Editors

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown, Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Christian Slavery

Conversion and Race in the Protestant Atlantic World

Katharine Gerbner

Copyright 2018 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gerbner, Katharine, author.

Title: Christian slavery: conversion and race in the protestant Atlantic world / Katharine Gerbner.

Other titles: Early American studies.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, [2018] | Series: Early American studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046031 | ISBN 9780812250015 (hardcover: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Slavery and the churchAtlantic Ocean RegionHistory. | SlavesReligious lifeAtlantic Ocean RegionHistory. | Christian convertsAtlantic Ocean RegionHistory. | Atlantic Ocean RegionRace relationsHistory.

Classification: LCC HT913 .G47 2018 | DDC 270.086/25dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046031

For Sean

Contents

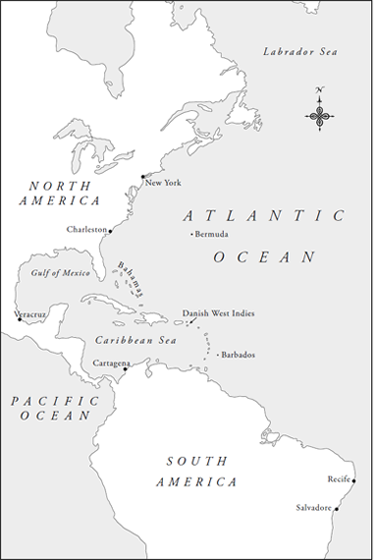

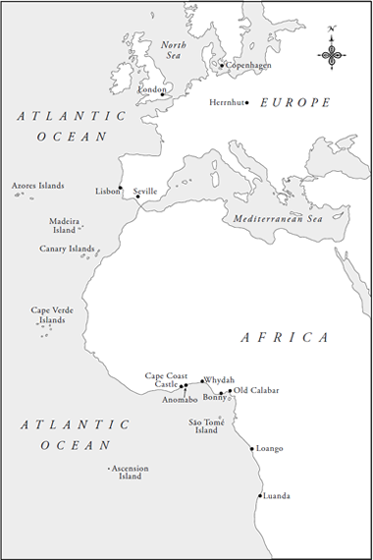

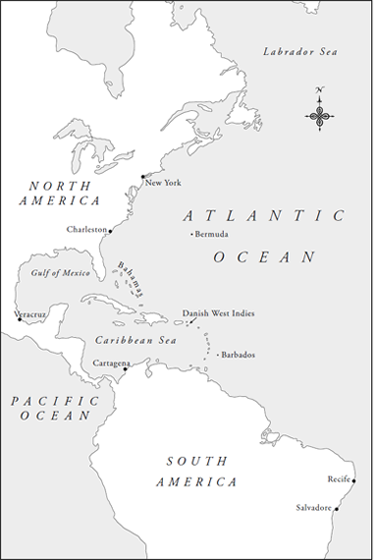

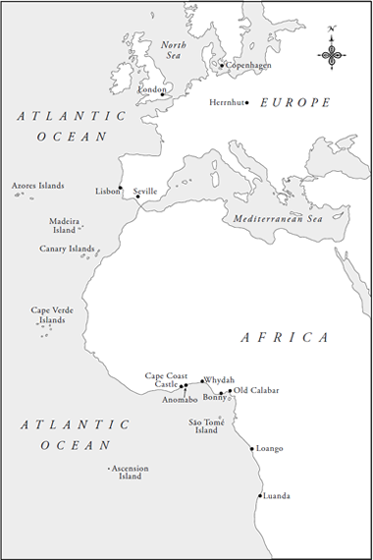

Map 1. The Atlantic World

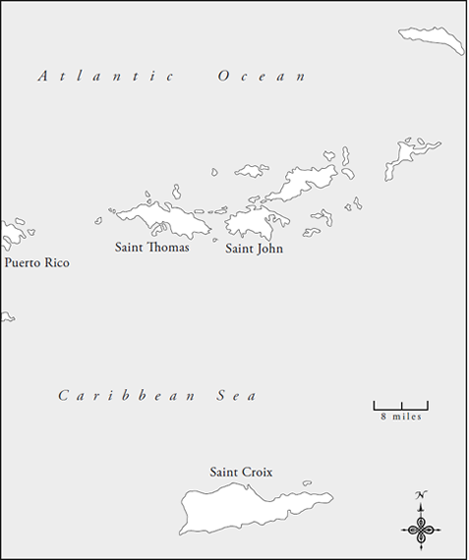

Map 2. The Caribbean

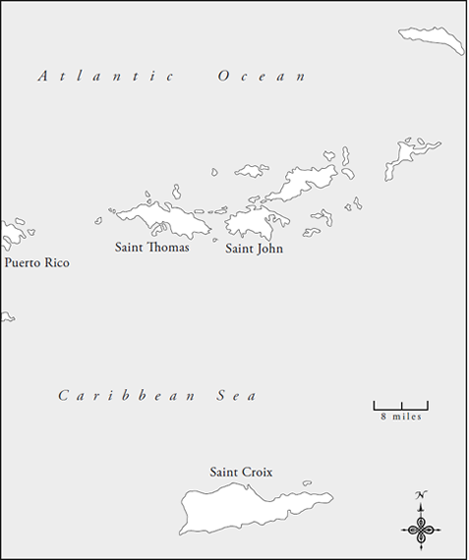

Map 3. The Danish West Indies

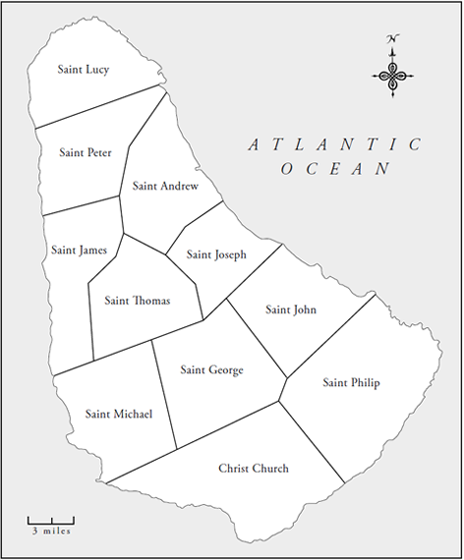

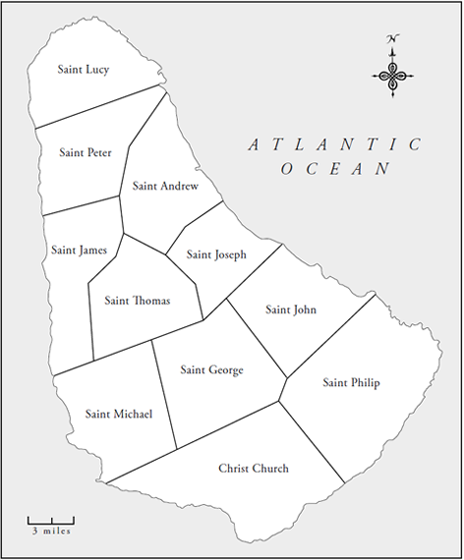

Map 4. Barbados Parishes

On November 16, 1651, a man named Lazarus entered the Anglican church in Christ Church parish, Barbados. As he walked toward the church doors, he passed the strong pair of Stocks where public punishments took place. The church itself was a wooden structure and one of the oldest buildings on the island. Constructed in 1629 just two years after the first English settlers arrived, the church would meet a tempestuous end: it was destroyed by flood in 1669 and washed out to sea. The second and third iterations of the church were destroyed by hurricane. But before the first church structure met its watery demise, it served as the site of Lazaruss baptism. Lazarus, who was described only as a negro in the church register, was the first Afro-Caribbean to receive baptism in the Anglican Church on Barbados. Neither his age nor place of birth were given, nor any indication of godparents or kin.

Lazaruss baptism challenged the emerging culture of slavery in the Protestant Atlantic world. The Anglican Church in Barbados was exclusive, the domain of slave owners and government officials. While most historians have downplayed the relevance of Christianity in the seventeenth-century Protestant Caribbean, viewing the sugar colonies as islands of depravity, the Anglican Church was central to the maintenance of planter power in Barbados and elsewhere. The planter elite believed that their status as Protestants was inseparable from their identity as free Englishmen. Like their counterparts in England, they purchased pews, memorialized themselves within church walls, and used the church as a place for both punishment and politics. Aside from the stocks that sat outside its doors, the church was the site of island elections and served as a community bulletin board where white inhabitants could post news about stolen goods or runaway slaves.

Unlike the parish churches in England, however, the Anglican Church in Barbados was restricted. It separated masters from their enslaved

Anticonversion sentiment was one of the defining features of Protestant slave societies in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. While enslaved Africans in Spanish, French, and Portuguese colonial societies were regularly introduced to Catholicism and baptized, whether willingly or not, Protestant slave owners in the English, Dutch, and Danish colonies tended to view conversion as inconsistent or incompatible with slavery. Their anticonversion sentiment was indicative of the changing meaning of Protestantism in the American colonies: over the course of the seventeenth century, Protestant planters claimed Christian identity for themselves, creating an exclusive ideal of religion based on ethnicitya construct that I call Protestant Supremacy.

Protestant Supremacy was the predecessor of White Supremacy, an ideology that emerged after the codification of racial slavery. I refer to Protestant Supremacy, rather than Anglican or Christian Supremacy, because this ideology was present throughout the Protestant American colonies, from the Danish West Indies to Virginia and beyond. It was most likely to develop in places with an enslaved population that was larger than the free population, such as Barbados, Jamaica, or South Carolina. In these colonies, Anglican, Dutch Reformed, and Lutheran slave owners conceived of their Protestant identities as fundamental to their status as masters. They constructed a caste system based on Christian status, in which heathenish slaves were afforded no rights or privileges while Catholics, Jews, and non-conforming Protestants were viewed with suspicion and distrust, but granted more protections.

When Protestant missionaries arrived in the plantation colonies intending to convert enslaved Africans to Christianity in the 1670s, they encountered slave societies that had already developed churches founded on exclusion. Planters regularly attacked missionaries, both verbally and physically, and blamed the evangelizing newcomers for slave rebellions, regardless of evidence to the contrary. Missionaries responded to this hostile environment by articulating and promoting a vision of Christian Slavery that reconciled Protestantism with bondage.

Christian Slavery was a polysemic concept. At the most basic level, it was an attempt to Christianize and reform slavery. Protestant theologians and missionaries drew on biblical descriptions of slavery as well as the ideal of the godly household to encourage slave owners to assume responsibility for the spiritual lives of their enslaved laborers. They also noted that Christian slavery had a long and well-established history in Europe and the Catholic American colonies. As missionaries faced opposition from slave owners, however, the meaning of Christian Slavery shifted. Missionaries increasingly emphasized the beneficial aspects of slave conversion, arguing that Christian slaves would be more docile and harder working than their heathen counterparts. They also sought to pass legislation that confirmed the legality of owning enslaved Christians. Over time, they integrated race into their arguments for Christian slavery. Since the ideology of Protestant Supremacy used religion to differentiate between slavery and freedom, missionaries suggested that race, rather than religion, was the defining feature of bondage.

Next page