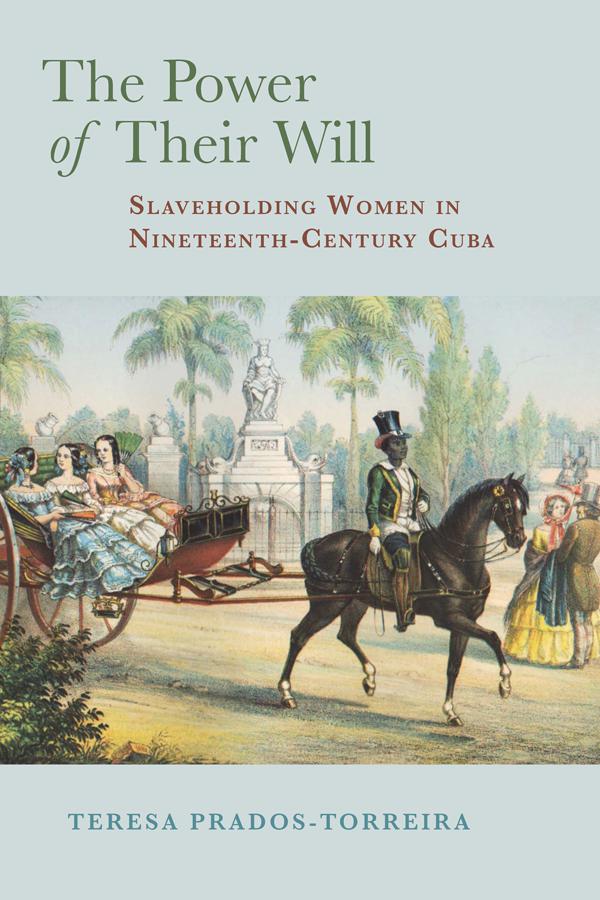

The Power of Their Will

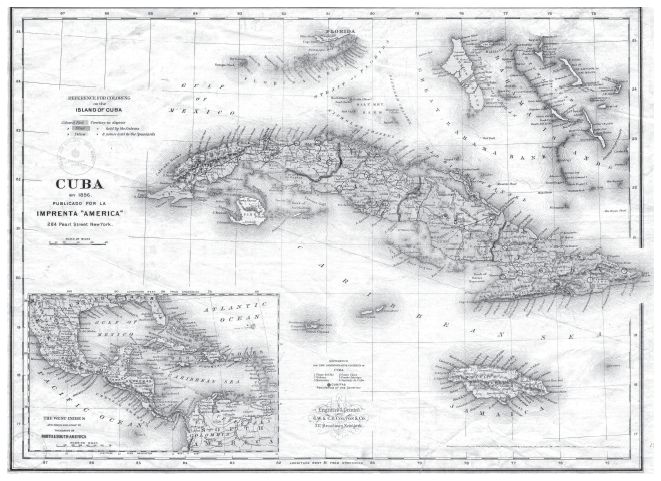

Frontispiece. Map of Cuba, 1896. New York: C. W. Colton, Imprenta Amrica. BNJM, Map Collection.

The Power of Their Will

SLAVEHOLDING WOMEN IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY CUBA

TERESA PRADOS-TORREIRA

The University of Alabama Press

Tuscaloosa

The University of Alabama Press

Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380

uapress.ua.edu

Copyright 2021 by the University of Alabama Press

All rights reserved.

Inquiries about reproducing material from this work should be addressed to the University of Alabama Press.

Typeface: Minion Pro

Cover image: El Quitrn, by Frdric Mialhe (1853); courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba Jos Mart

Cover design: Michele Myatt Quinn

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-8173-2079-9

E-ISBN: 978-0-8173-9335-9

To my dear friend Nancy Machado (19622020). As subdirectora of the Jos Mart National Library in Havana for many years, Nancy helped me, and hundreds of other scholars, find what we were looking for and what we didnt know was there.

Contents

Figures

Acknowledgments

I THANK WENDI SCHNAUFER, senior acquisitions editor of the University of Alabama Press, for all her help and her positive spirit. It has been a pleasure to work with her. I also thank Joanna Jacobs, assistant managing editor at the press, and freelance copyeditor Lys Weiss, of Post Hoc Academic Publishing Services, for their helpful revisions and suggestions.

The members of the Windy City Writing GroupBenjamin Johnson, Andrae Marak, Margaret Power, Michael Staudenmaier, Ellen Walsh, and Neici Zellerhave been a model of collegiality. They read every chapter of my manuscript, identified the flaws, and encouraged me to move forward with this project.

In Santiago de Cuba, La Casa de Africa provided a wonderful platform for scholarly discussion with its annual conference. The archivist Maria Antonia Reina helped me find documents from the Archivo Provincial. My friend Damaris Torres Ellers, with whom I share many interests, assisted with information and guidance, as did several other members of the Universidad de Oriente History Department. Maciel Reyes, a promising young scholar, was also invaluable in helping me find information on coffee planters and their culture, as well as addressing every question I came up with. I remember fondly our many talks on nineteenth-century Cuban wills, a subject she masters. Nancy Machado, the subdirectora of the Jos Mart National Library in Havana, was a dear friend and the best possible ally a scholar could have. I benefited greatly from her knowledge of the librarys collection and her understanding of Cuban bureaucracy. Her death, which occurred as I was proofreading these pages, is a devastating loss for both her friends and the academic community.

The staff of the Columbia College Chicago Library was a constant and reliable source of support.

I am also grateful to Steve Asma, Rojhat Avsar, Andrew Causey, Melanie Chambliss, Carmelo Esterrich, Rami Gabriel, Olga Goldenberg, Kate Hamerton, Robert Hanserd, Eliza Nichols, Michelle Yates, and the rest of my department at Columbia College Chicago, for being excellent colleagues.

I thank my friend Mara Ochoa for her insightful comments after reading the whole manuscript, and Allison English for keeping my body and mind in sync during the grueling process of writing the book. Namaste.

I was able to count on my siblingsMayi, Dolores, Alfredo, Lourdes, Miguel, and Rocioto help me translate obscure terms and much, much more.

I am particularly in debt to my husband, Joel Bleifuss, and to my sons, Adrian, Diego, and Eloy, for their help editing my manuscript, and for their love and support.

Introduction

THIS BOOK ADDRESSES a subject that historians of Cuba have largely neglected: the interactions and social dynamics between female slaveholders and the enslaved men, women, and children under their control in nineteenth-century Cuba. It examines the ways in which slave mistresses authority both shaped and failed to shape the institution of slavery, and how their slaveholding role defined their own lives and the lives of their slaves.

Cuba became a Spanish colony after Columbus landed on the island in 1492. From the beginning of the colonization period, Spain brought enslaved Africans to Cuba to work in the mines. This labor force was especially needed as Old-World diseases and the exploitation of the native population had genocidal consequences throughout the Americas. Slaves were also sent to work in the small sugar mills that proliferated throughout the island and in construction sites in growing towns. But the enslaved persons were most often domestic workers in private homes. In the late eighteenth century, after Saint Domingues slave rebellion and the resulting collapse of its rich economy, Cuba transformed itself into a leading producer of sugar and coffee, two commodities that were becoming increasingly popular in Europe and the former American colonies. In 1789, encouraged by the Cuban planter class and in an attempt to emulate the British and French economic models, the Spanish crown put an end to what had been up until then a foreigners monopoly on the slave trade, and opened the market in human beings to its subjects. Spanish entrepreneurs seized their opportunity, particularly after 1807, the year when Great Britain ended its participation in the slave trade and the British slave merchants sold their knowledge and establishments on the African coast to the Spanish newcomers. Thus, in a tragic twist, Spain responded to the rise of abolitionist ideals and the subsequent decline of slavery throughout the Atlantic with a massive expansion of slave plantations in Cuba. Between the late 1790s and 1830, more than three hundred thousand Africans were captured, enslaved, and shipped to the island. Dale Tomich has coined the term second slavery to describe the enormous growth of Cubas (and Brazils) plantation economy in the early nineteenth century, which resulted from the abolition of enslaved labor in so many other areas of the world. Despite the agreements Spain signed with Britain in 1817 and then again in 1835 renouncing the slave trade, Africans continued to be brought by force to Cuba until 1867, if not longer. In 1817, the islands slave population was recorded at 199,000. By the 1840s it had increased to 436,000, with enslaved people and freed people of color making up 58 percent of the Cuban population, numbers that inspired fear among the white inhabitants. Between 1501 and 1866, more than 778,000 Africans were torn from their homelands and brought to work for the benefit of the Cuban slaveholding class.

Current scholarship on the Caribbean highlights the importance of the regions slavery in the development of global capitalism. Coffee and, even more so, sugar production were intensely competitive businesses that aimed at maximum productivity and financial profit. Nineteenth-century Cuban planters can rightly be characterized as modern capitalists seeking profits in a highly competitive international market. They were willing to experiment with crops and invest in the latest technical innovations. And although the Spanish empire had entered its twilight years, Spain was fully invested in protecting the great wealth that resulted from slave labor in its colonies.