2016 by Vanderbilt University Press

Nashville, Tennessee 37235

All rights reserved

First printing 2016

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Manufactured in the United States of America

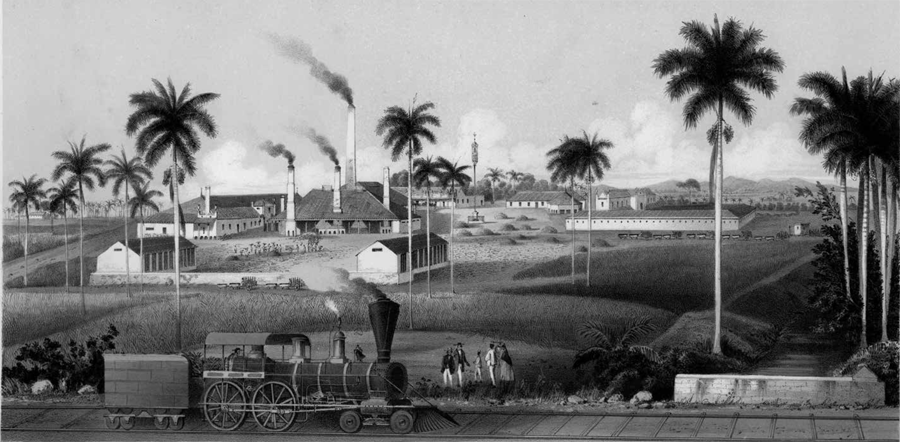

: Lithograph showing a sugar refinery plant in Cuba.

Title: Ingenio Acana propriedad del Seor Dn. J. Eusebio Alfonso // dibujado y litogrdo. por Edo. Laplante; litografia de L. Marquier. Illustration from Los ingenios : coleccion de vistas de los principales ingenios de azucar... de Cuba... / por Justo G. Cantero (Habana: Impreso en la litografia de L. Marquier, 1857)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file

LC control number 2016030960

LC classification number HT1078 .S55 2016

Dewey class number 306.3/6209729109/034dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2016030960

ISBN 978-0-8265-2109-5 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8265-2111-8 (ebook)

Acknowledgments

The Merchant of Havana began and, over several years, developed under the intelligent, patient guidance of Ruth Hill. She is the source of anything that may be worthwhile in this book.

I am deeply grateful to my teachers in the Department of Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese at the University of Virginia. Special thanks go to Fernando Oper, Gustavo Pelln, and Alison Weber. I found valuable support in Asher Biemann and the Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellows of Jewish Studies program at the University of Virginia, which he organized. The Public Humanities Fellowship Program in South Atlantic Studies, sponsored jointly by the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia and the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, provided a venue to calibrate several of my arguments. Research in Havana was made possible by a Charles Gordon Reid Fellowship from the University of Virginia, as well as by the generous assistance of Ana Mara Gonzlez Marfud, Carlos Federico Mart Brenes, Ariel Camejo, and Jos Antonio Baujn Prez at the University of Havana. I thank Jorge and Nardy Len for their friendship and hospitality.

I have exceptionally supportive colleagues in the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures at Baylor University. Heidi Bostics counsel and encouragement have been invaluable, and a chapter of this study has benefitted from her insightful reading. Elizabeth Willingham graciously invited me to present some of my ideas at a conference panel she organized. Marian Ortuo provided smart critique of a portion of this book. My friends in the Spanish Division have been generous and kind: Frieda Blackwell, Rafa Climent Espino, Jan Evans, Guillermo Garca Corales, Baudelio Garza, Karol Hardin, Paul Larson, Fred Loa, Linda McManness, Alex McNair, Janet Norden, Manuel Ortuo, Marian Ortuo, Lilly Souza Fuertes, Mike Thomas, and Beth Willingham. Adrienne Harris and Andy Wisely are real-life superheroes. Roberto Pesce and Serena Dal Pont have made life in the heart of Texas delightful and delicious, as has Stephen Pluhek. Robyn Driskell has advocated for me and supported my research. Two summer sabbaticals and a semester of research leave provided by Baylors College of Arts and Sciences afforded me the time to complete this book.

The Latin American Jewish Studies Association has granted me several opportunities to develop my ideas in dialogue with a community of thoughtful peers. I am especially indebted to my tremendous colleagues Alan Astro, Naomi Lindstrom, and Darrell Lockhart. Rosa Perelmuter has hospitably encouraged my participation on two LAJSA conference panels that she organized. I am very fortunate to have David Foster as a mentor. During the National Endowment for the Humanities summer program Jewish Buenos Aires (which has sadly been eliminated along with all overseas NEH summer seminars) that Foster led, this project benefitted from his consultation and from that of Charles Heath II, Yitzhak Lewis, Matt Losada, and Yovanna Pineda.

It has been a pleasure to work with Eli Bortz on this book. I am grateful to him and to the editorial staff at Vanderbilt University Press. I wish to express my thanks to the anonymous readers; this is a better study thanks to their critiques.

Karen Stolley is an excellent colleague and considerate supporter of my work. I adjusted several of the ideas in this book thanks to a stimulating conference panel organized by Agnes Lugo-Ortiz. Tom Finnegan is an especially skilled editor. Tony Cella, Ashley Kerr, Andrea Meador Smith, Faith Harden, David Luis-Brown, and Gillian Price provided incisive readings of portions of this study. I owe a special debt of gratitude to Zach Ludington for his enthusiastic willingness to read the manuscript in its entirety and for his smart commentary.

Christopher Schmidt-Nowara passed away during the completion of this book. While our relationship was limited to the exchange of e-mail, this did not prevent him from responding to my queries with enthusiasm and humility.

A prior version of leccin de artculos and the Policy of Buen Tratamiento in Revista Hispnica Moderna. I thank the editors of these journals for permitting me to reproduce those arguments here.

Lastly, my family has been essential to the writing of this book. Jack, Cayman, Eshu, Grandpa, Lee, How, Jess, Miles, and Skylarthank you. This book is dedicated to my parents for their enduring support and to , , .

THE MERCHANT OF HAVANAIntroduction

IN HIS TRAVEL MEMOIR Notes on Cuba (1844), John George F. Wurdemann, a South Carolina physician convalescing from tuberculosis on the island in the winter of 1843, discusses how many [Cubans] would linger to look at the Inglesis, as they called us to our faceswhen we were absent the term Judios (hudeos), Jews, was applied to us, a generic appellation given to all foreigners.

The Judaized foreigners who invaded the creole imaginary did so in the wake of the islands first sugar boom, which coincided with the rise of and contest over the framework of Spanish imperial liberalism and was stimulated by what Dale Tomich has described as a new social-economic form on which an accelerated rhythm was imposed with the introduction of the railroad, the integration of the islands sugar economy into the world-scale circuits of capital, and the expansion and intensification of slave labor. Further, the Jew was an unwilling textual surrogate for the licentious Spanish Catholic who had fathered children with black female slaves. Transracial sex, or mestizaje, was looked on with deep apprehension by many creoles because, like industrial capitalism and the global rebalancing of trade, it threatened to overturn the established order. To be sure, the discursive practice that looked to restore stability to colonial society and subjectivity through the metaphorical Jew was operative on multiple fronts.

At this point, a short proviso is in order. It must be recognized that actual religious convictions are irrelevant to the vitality of the tropes that aligned Cubas nineteenth-century merchants with conceptions of Jewishness. The perlocutionary effectiveness of anti-Semitism, as several scholars have indicated, need not have anything to do with whether or not its targets are those who have historically grounded identities in those material signifiers, as Daniel and Jonathan Boyarin designate the group of people that for simplicitys sake, and following Zygmunt Bauman, I will call empirical Jews.