Evelyn Jennings - Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana: State Slavery in Defense and Development, 1762-1835

Here you can read online Evelyn Jennings - Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana: State Slavery in Defense and Development, 1762-1835 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: LSU Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana: State Slavery in Defense and Development, 1762-1835

- Author:

- Publisher:LSU Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana: State Slavery in Defense and Development, 1762-1835: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana: State Slavery in Defense and Development, 1762-1835" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

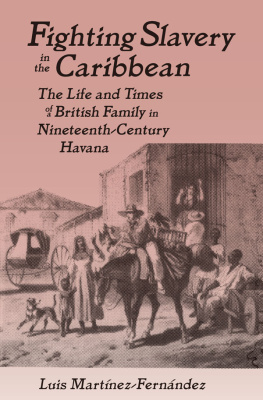

Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana examines the political economy surrounding the use of enslaved laborers in the capital of Spanish imperial Cuba from 1762 to 1835. In this first book-length exploration of state slavery on the island, Evelyn P. Jennings demonstrates that the Spanish states policies and practices in the ownership and employment of enslaved workers after 1762 served as a bridge from an economy based on imperial service to a rapidly expanding plantation economy in the nineteenth century.

The Spanish state had owned and exploited enslaved workers in Cuba since the early 1500s. After the humiliating yearlong British occupation of Havana beginning in 1762, however, the Spanish Crown redoubled its efforts to purchase and maintain thousands of royal slaves to prepare Havana for what officials believed would be the imminent renewal of war with England. Jennings shows that the composition of workforces assigned to public projects depended on the availability of enslaved workers in various interconnected labor markets within Cuba, within the Spanish empire, and in the Atlantic world. Moreover, the site of enslavement, the work required, and the importance of that work according to imperial priorities influenced the treatment and relative autonomy of those laborers as well as the likelihood they would achieve freedom.

As plantation production for export purposes emerged as the most dynamic sector of Cubas economy by 1810, the Atlantic networks used to obtain enslaved workers showed increasing strain. British abolitionism exerted additional pressure on the slave trade. To offset the loss of access to enslaved laborers, colonial officials expanded the states authority to sentence deserters, vagrants, and fugitives, both enslaved and free, to labor in public works such as civil construction, road building, and the creation of Havanas defensive forts. State efforts in this area demonstrate the deep roots of state enslavement and forced labor in nineteenth-century Spanish colonialism and in capitalist development in the Atlantic world.

Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana places the processes of building and sustaining the Spanish empire in the imperial hub of Havana in a comparative perspective with other sites of empire building in the Atlantic world. Furthermore, it considers the human costs of reproducing the Spanish empire in a major Caribbean port, the states role in shaping the institution of slavery, and the experiences of enslaved and other coerced laborers both before and after the beginning of Cubas sugar boom in the early nineteenth century.

Evelyn Jennings: author's other books

Who wrote Constructing the Spanish Empire in Havana: State Slavery in Defense and Development, 1762-1835? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.