Contents

Guide

ALSO BY STEPHEN BOURNE

Aunt Esthers Story (ECOHP, 1991)

Brief Encounters: Lesbians and Gays in British Cinema 19301971 (Cassell, 1996)

Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television (Cassell/Continuum, 2001)

Elisabeth Welch: Soft Lights and Sweet Music (Scarecrow Press, 2005)

Mother Country: Britains Black Community on the Home Front 19391945 (The History Press, 2010)

The Motherland Calls: Britains Black Servicemen and Women 19391945 (The History Press, 2012)

Esther Bruce: A Black London Seamstress (History and Social Action Publications, 2012)

Black Poppies: Britains Black Community and the Great War (The History Press, 2014; 2nd edition 2019)

Evelyn Dove: Britains Black Cabaret Queen (Jacaranda Books, 2016)

Fighting Proud: The Untold Story of the Gay Men Who Served in Two World Wars (I.B. Taurus, 2017)

War to Windrush: Black Women in Britain 19391948 (Jacaranda Books, 2018)

Playing Gay in the Golden Age of British Television (The History Press, 2019)

Under Fire: Black Britain in Wartime 19391945 (The History Press, 2020)

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St Georges Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Stephen Bourne, 2021

The right of Stephen Bourne, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9780750999106

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Three Playwrights: Mustapha Matura, Michael

Abbensetts and Alfred Fagon

AUTHORS NOTE

Thanks go to David Hankin for digitally remastering some of the photographs; Keith Howes for his constructive comments on an early draft of the book; and Simon Wright, my editor at The History Press, who in the summer of 2020 asked me if I had an idea for a new book. This is the result.

I would like to recommend two online resources for further research: the University of Warwicks British Black and Asian Shakespeare Performance Database (bbashakespeare.warwick.ac.uk) and the National Theatres Black Plays Archive (www.blackplaysarchive.org.uk).

In Deep Are the Roots, the terms Black and African Caribbean refer to African, Caribbean and British people of African heritage. Other terms, such as West Indian, Negro and coloured are used in their historical contexts, usually before the 1960s and 1970s, the decades in which the term Black came into popular use.

Though every care has been taken to trace or contact all copyright holders, I would be pleased to rectify at the earliest opportunity any errors or omissions brought to my attention.

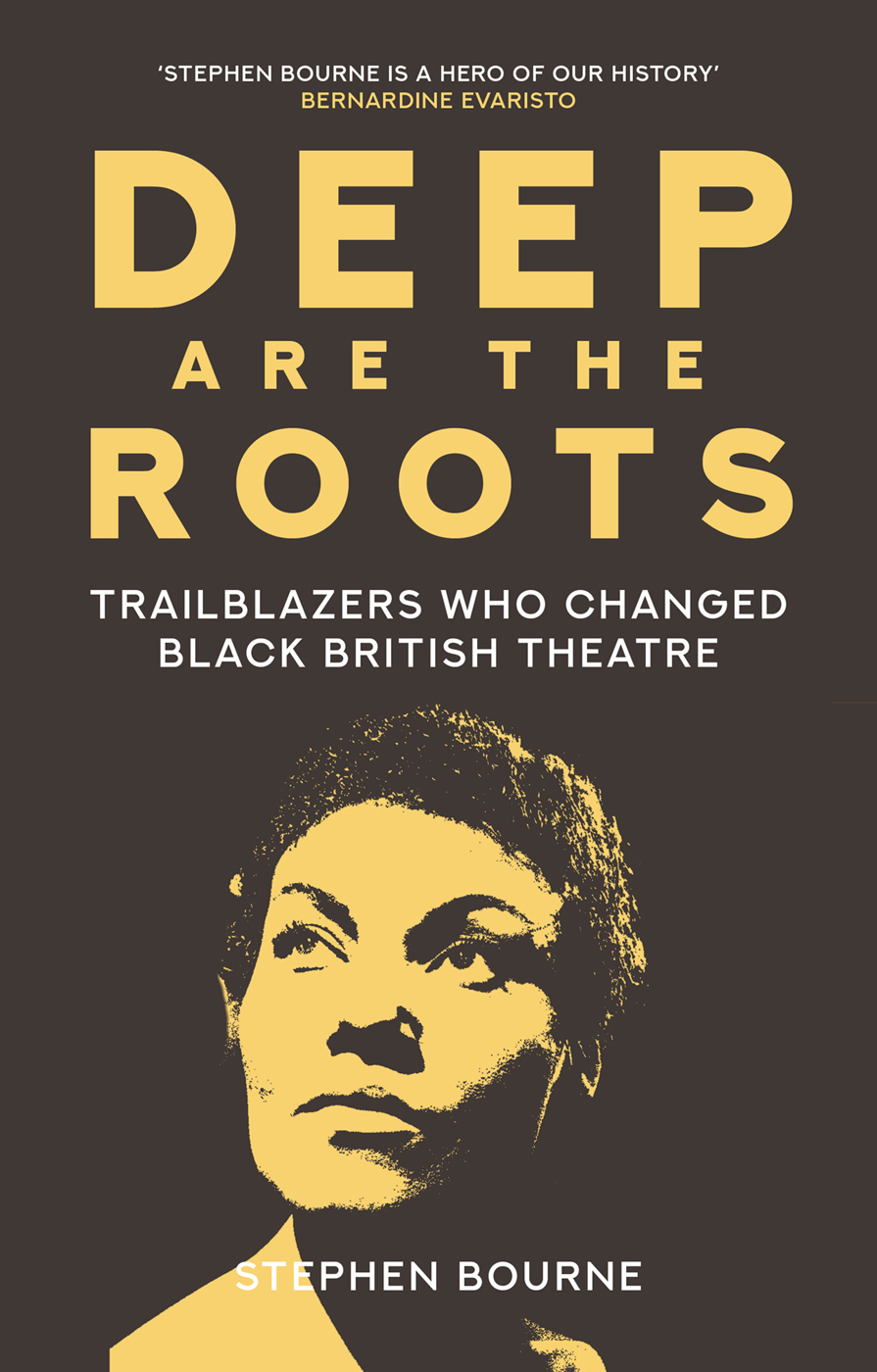

PREFACE

Deep Are the Roots evolved from the time I was invited by the Theatre Museum in Londons Covent Garden to loan items from my collection to its Let Paul Robeson Sing! exhibition in 2001. Little did I realise that it would lead to me cataloguing its Black theatre collection. I drew the museums attention to the fact that its vast archive included programmes, press cuttings, photographs, books and other material relating to Black theatre in Britain from as early as 1825, but that researchers who visited the museums study room were not aware of the richness of what existed.

Funded by a small research grant from The Society for Theatre Research, I began by surveying the early years of Black British theatre from the 1820s to the 1970s under the supervision of Susan Croft, who was the museums curator of contemporary performance. The stage careers of African American actors such as Ira Aldridge and Paul Robeson had already been well documented, and so it was not difficult to find material relating to them. It was fascinating to uncover the forgotten work of Black actors and writers from Africa, Britain and the Caribbean. Susan then put together the Theatre Museums publication Black and Asian Performance at the Theatre Museum: A Users Guide, published in 2003, which included a database I had compiled of landmark Black British theatre productions from 1825 to 1975, while Dr Alda Terracciano compiled a similar database covering the period from 1975 to 2000.

Later on, I applied for and received a Wingate Scholarship in 2011 to further my research into early Black theatre in Britain. In 2012 I was interviewed for the documentary Margins to Mainstream: The Story of Black Theatre in Britain, and in July 2013 I participated in Warwick Universitys Shakespeare symposium with the presentation Beyond Paul Robeson Black British Actors and Shakespeare 19301965.

And yet publishers repeatedly rejected my proposal for a book on the subject. Your book is too niche, one of them said. Another told me that Black people do not buy books, so there is no market for them. There was one exception: a young and enthusiastic editor did show an interest and he was keen to commission the book, but he was overruled by his editorial advisory board. Disheartened, I gave up and put the proposal away.

The landscape changed dramatically in 2020 with the Black Lives Matter movement, which drew attention to the Black presence in Britain both historically and in contemporary life. Almost immediately two of the publishers who had rejected my proposal contacted me and asked me if I had any ideas for Black history books, but they were too late. I had just been contacted by Simon Wright, my editor at The History Press, and I had sent him the proposal for this book. A contract was immediately negotiated. However, I decided to write Deep Are the Roots in a different way to my previous books.

When I started out as a professional writer, I was always told to write objectively, not in the first person. I had never been encouraged to personalise my books. That is the academic way of writing history books; but with Deep Are the Roots, it was not going to be my way. For years I had enjoyed personal connections and friendships with many of the people I wanted to include in the book, so I wanted to avoid distancing myself from them by being objective. This is why the reader will find Deep Are the Roots a personal history and not an objective, academic one.

It is the personal relationships and anecdotes that are missing from so many books I have read on this subject not that there have been very many. Two of my favourite academic works on the subject are Errol Hills