About the Authors

Fitzroy Maclean held a number of senior posts in the diplomatic service, the armed forces and the government.

Magnus Linklater is a regular contributor to The Times, and has written widely on Scottish history.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Art of the Picts:

Sculpture and Metalwork in Early Medieval Scotland

The Highland Clans

India: A Short History

Turkey: A Short History

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

For Veronica

AUTHORS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks are due to Lady Hesketh, Lady Antonia Fraser, Miss Janet Glover and Sir Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk for their invaluable comments and criticism; also to Mr John Colville, C.B., C.V.O., for the additional verse of the National Anthem quoted on page 111; and finally to Miss Priscilla Thorburn for her invaluable help in preparing the text for publication.

PUBLISHERS NOTE

For this fifth edition, Sir Fitzroy Macleans analysis of Scotlands place in the United Kingdom in the early 1990s has again been left unchanged. Magnus Linklater, who contributed chapters 8 and 9 for previous editions, has now written chapter 10, bringing the story up to date.

CONTENTS

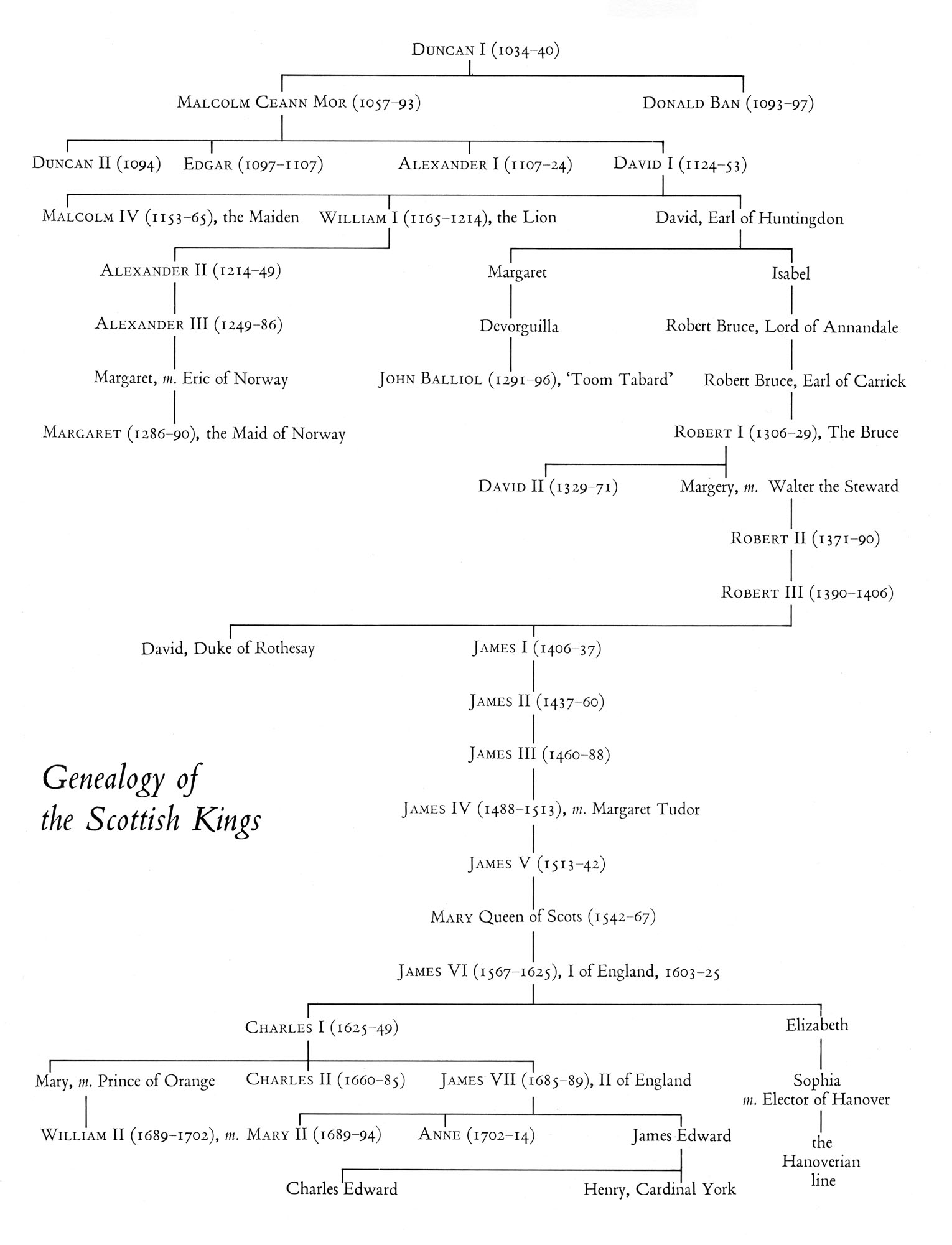

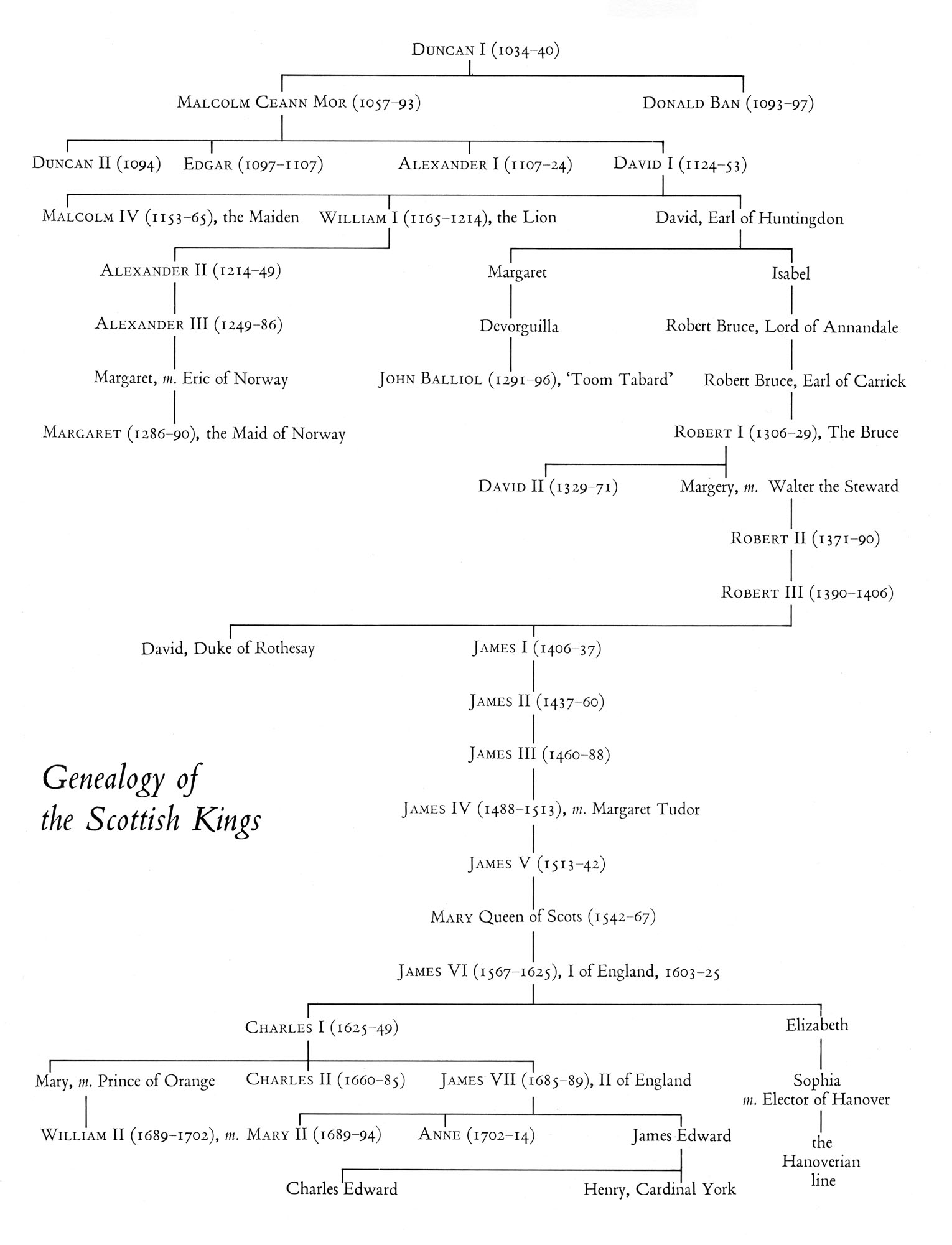

The mists of antiquity / the Romans / four races / the coming of Christianity / Columba / the Norsemen / Malcolm Ceann Mor / the Normans / the French Alliance / the Maid of Norway / the Succession / Edward I of England

William Wallace / Robert Bruce / Bannockburn / the House of Stewart / the great nobles / the Kingdom of the Isles / the Red Harlaw

James IV / the Renaissance / the Highland Clans / the Auld Alliance / Flodden Field / brawling nobles / the Rough Wooing / the coming of the Reformation / John Knox / Mary Queen of Scots / her abdication

A succession of Regents / James VI and the Kirk / No Bishops, no King / the Union of the Crowns / the rise of Clan Campbell / Charles I / the National Covenant / Montrose / Cromwell

The Commonwealth / the Restoration / Charles II / the Covenanters / the Killing Time / James VII / William and Mary / Killiecrankie / murun mor nan Gall / Glencoe / Darien / the Union

The Fifteen / Old Mr Melancholy / the Nineteen / the Forty/Five / Charlies Year

Lochaber no more / The more mischief the better sport / the Crown as link / Industrial Revolution / political stagnation / a flowering of the arts / return of confidence / the Empire / the established Church / the Reform Bill / the shifting balance of the parties / more devolution / the Scottish economy / union or separation?

Magnus Linklater

Proposals for a Parliament / the successful referendum / the new coalition / Scots in charge

Magnus Linklater

The new seat of Scottish democracy / the old order weakened / global economic crisis / an overall majority

Magnus Linklater

A referendum on independence / the SNP in government / Britains exit from the European Union

First Written Records

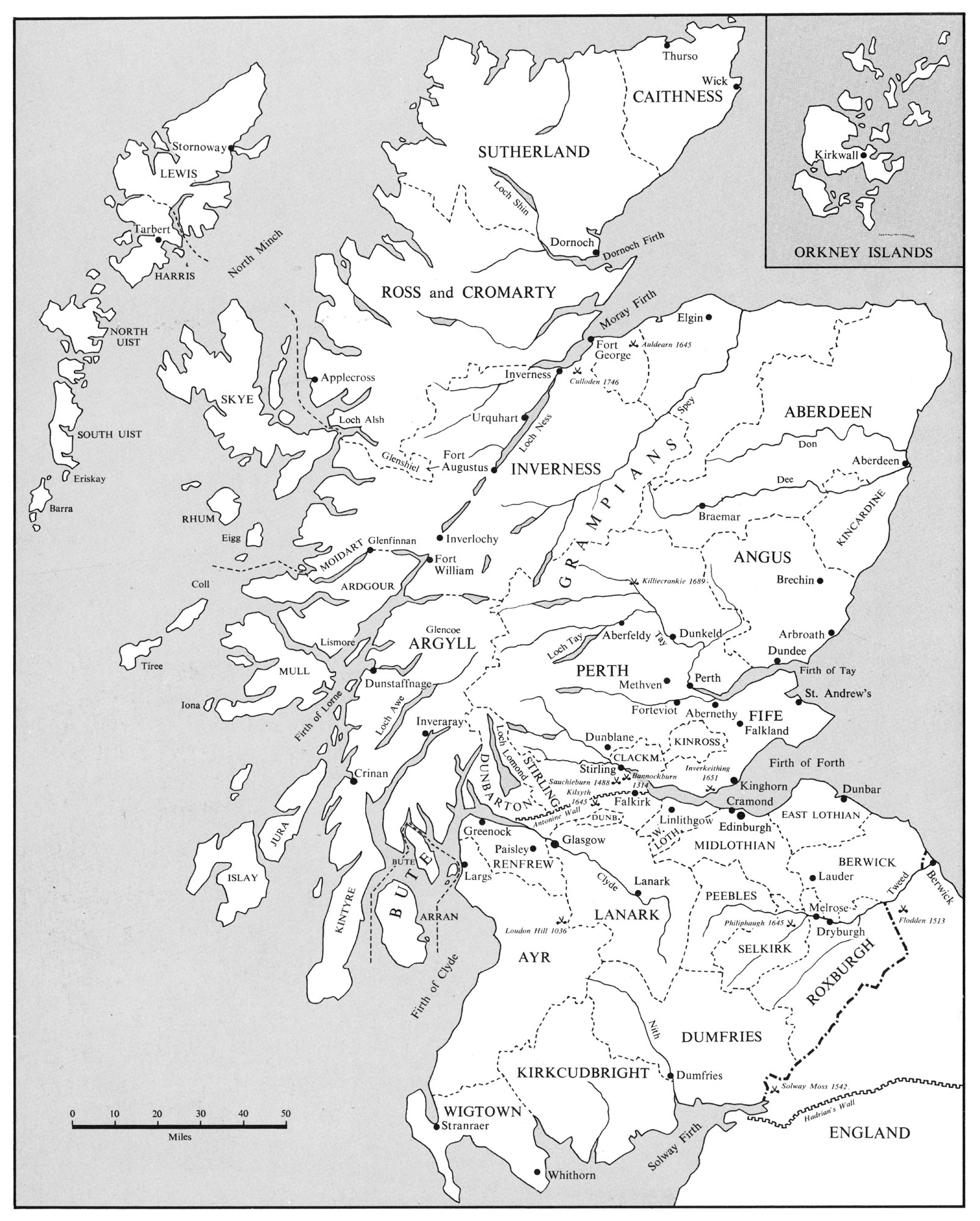

The early history of Scotland, like that of most countries, is largely veiled by what are known as the mists of antiquity, in this case a more than usually felicitous phrase. From piles of discarded sea-shells and implements of bone and stone, from monoliths and megaliths and mounds of grass-grown turf, from crannogs and brochs and vitrified forts, painstaking archaeologists have pieced together a handful of basic facts about the Stone and Bronze Age inhabitants of our country and about the first Celtic invaders who followed them in successive waves a good many centuries later. But it is not until the beginning of our own era that we come upon the first written records of Scottish history. These are to be found in the works of the Roman historian Tacitus, whose father-in-law, Cnaeus Julius Agricola, then Governor of the Roman Province of Britain, invaded what is now southern Scotland with the Ninth Legion in the year ad 81.

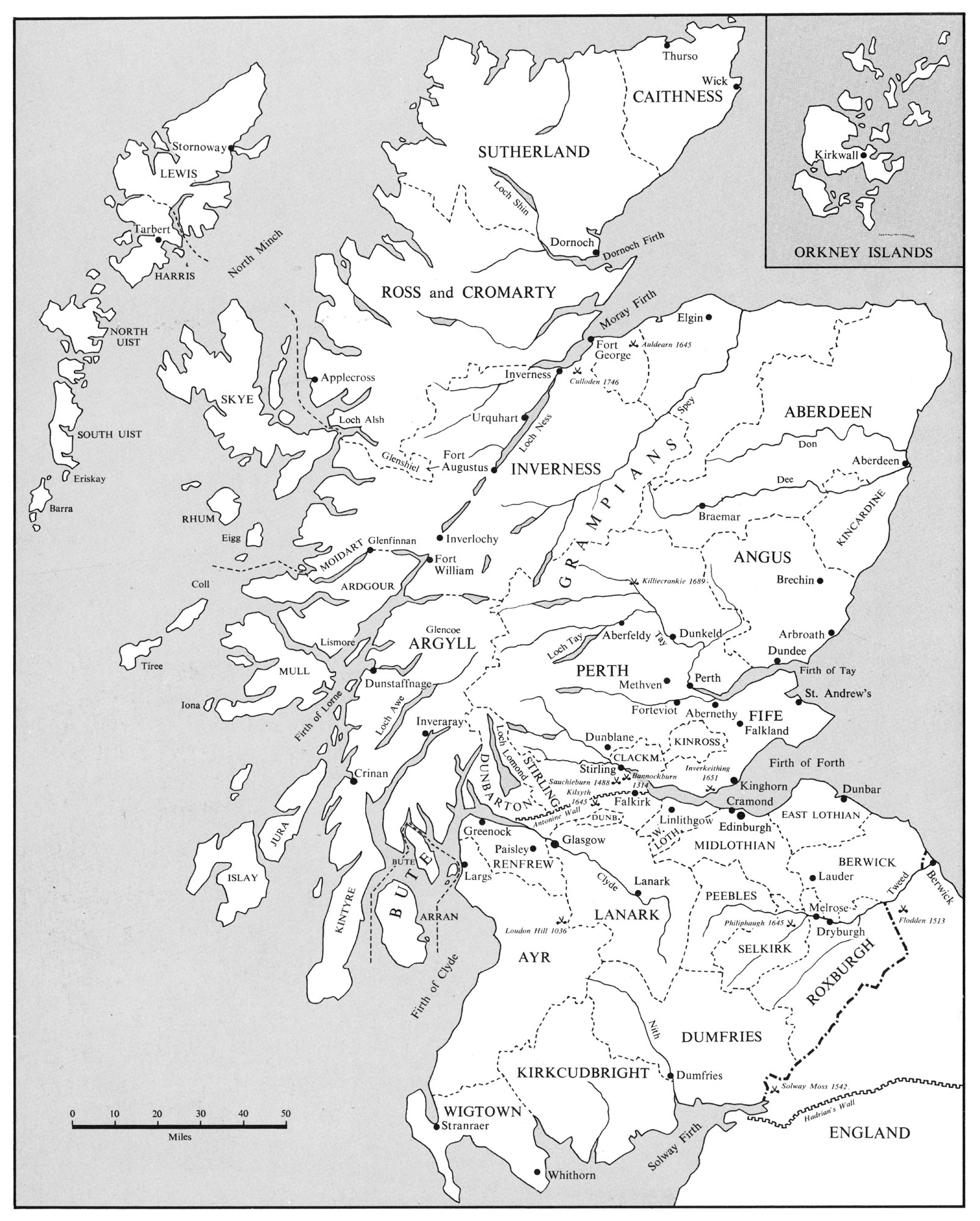

From Tacitus we learn that, having advanced from a base in northern England as far as the Forth-Clyde line, which it was his intention to hold by means of a chain of forts, Agricola established his headquarters at Stirling. Keeping in touch with his fleet as he pushed northwards, he encountered and heavily defeated the native Caledonians under their chieftain Calgacus in a pitched battle at Mons Graupius in eastern Scotland, which some identify as the Hill of Moncreiffe.

This was in the late summer of 83. After wintering on the banks of the Tay, Agricola was proposing to continue his advance northwards when early in 84 he suddenly received orders from Rome to withdraw. Perdomita Britannia et statim omissa, wrote Tacitus sourly, Britain conquered and then at once thrown away. Subsequent Roman strategy towards Scotland seems to have been mainly defensive rather than offensive in intention. In 121 the Emperor Hadrian himself visited Britain and built his wall from Solway to Tyne. And twenty years after this we find the then Governor of Britain, Lollius Urbicus, building in his turn the Antonine Wall from Forth to Clyde.

Later again, in 208, the old Emperor Severus, no doubt encouraged by the series of spectacular victories he had won from Illyria to the Euphrates, tried a new approach to the problem, building himself a naval base at Cramond and then pushing northwards as far as the Moray Firth. But his Caledonian adversaries, wiser than their forefathers, avoided a pitched battle, and after three years of inconclusive skirmishing old Severus was back at Eboracum or York, dying from his exertions.

The tangled mountain mass of the Grampians and the dense forest which at that time covered much of central Scotland favoured guerrilla warfare and the Caledonians took full advantage of them. Not long after Severus campaign the Romans abandoned the Antonine Wall and evacuated their northerly bases. For a hundred years or more Hadrians Wall remained the Roman frontier and Britain to the south of it enjoyed a period of relative peace. Then, in the second half of the fourth century the tribes began to break through from the north in a series of ever bolder and more successful raids. At the same time Saxon pirates started to attack from across the North Sea. Had the Romans not had their hands full elsewhere, they might have returned to their original project of trying to conquer Scotland. As it was, trouble nearer home made it necessary for the Legions to be recalled and by the end of the fourth century the last remaining Roman outposts in Scotland had been abandoned. Thus Scotland only encountered the might of Rome spasmodically and never became a true part of the Roman Empire or enjoyed save at second hand the benefits or otherwise of Roman civilization.

Next page