Contents

Compiling Collins Little Book of Scottish History has been a wonderful challenge. With thousands of years of history as source material there is an extraordinary wealth of information and facts to call on, and so many famous and not so famous lives whose stories deserve to be told, from Neolithic times through to the digital age of the 21st century.

With Collins Little Book of Scottish History we have attempted to give as broad an overview as possible. Yes, we cover the more familiar topics of William Wallace, Robert the Bruce, Mary, Queen of Scots, Robert Burns, the battles of Bannockburn and Culloden, the Highland clans, and the historic role of Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. However, we also recognize the equally important events that shaped Scotland into the country it is today: a nation that was forged first by the union of the Picts and Gaelic-speaking incomers from Ireland, and grew over time to incorporate the Lowland kingdoms of Lothian and Strathclyde, and the formerly Scandinavian-ruled Hebrides and Northern Isles. In doing so we trace the development of a nation and people that were given the name Caledonia by the Romans, then Alba by the Gaels, before settling on Scotland, the land of the Scots.

The kingdom of Scotland endured for 700 years through adversity, conflict, and seemingly insurmountable odds until the Union of Crowns with England in 1603 and the Union of Parliaments in 1707. However, even after Union, the Scottish people have retained their independent culture, heritage, and spirit into the modern age, both at home and abroad. After 1707 itinerant Scots travelled the globe in ever-greater numbers, taking their language, their religion, and their history with them to their new homes. Over time this Scottish history, as history always does, became interwoven with mythology and legend to create a rich and colourful tapestry, so wherever possible we have tried to differentiate the fact from the myth or explain why the legend became so important.

By giving due recognition to the history of Scotland and the Scots after 1707, we will also attempt to bring the story up to date. Scots played a pivotal role in the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and the British Empire. In the process they not only built modern Scotland, but also an extraordinary amount of the modern world, from the telephone to television, and from radio waves to penicillin. Scotlands ongoing scientific, industrial, and medical legacy is another chapter of the story that we will investigate, alongside such iconic aspects of the nations culture as tartan, whisky, and golf. For it is only by examining all elements of Scotland and the Scots that we gain a true picture of the country and its people.

History matters, for it tells us who we are, how we got here, and why the world is the way it is. And for a country such as Scotland, where the question of national identity can have many different and sometimes contradictory answers, history matters more than for most. The Little Book of Scottish History is our attempt to provide a concise summary of over 2000 years of Scottish history. We hope that it answers and explains all the questions you ever wanted to ask, as well as a few that you never even thought to. We also hope you enjoy Collins Little Book of Scottish History as an informative and entertaining introduction to a subject that has never had such a large global audience. For that is the most wonderful thing about history: there are always more stories to be told.

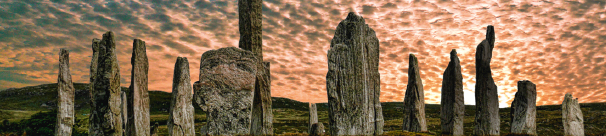

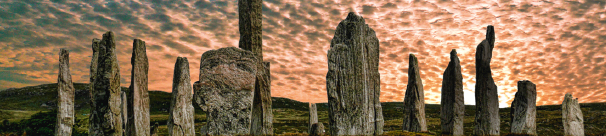

Located on the western fringes of the European continent, Scotland was one of the last regions to be inhabited after the end of the last Ice Age. The first humans arrived over 9,000 years ago, around 7,000 BC, and were nomadic hunters and gatherers, but settled as farmers. The oldest surviving evidence of their Neolithic society is found at the village of Skara Brae in Orkney, which dates back 5,000 years to around 3,000 BC. Orkney is a treasure trove of reminders of prehistoric Scotland, with Skara Brae and the magnificent burial tomb of Maes Howe as its centrepiece. Further west, on the Hebridean island of Lewis, stands the equally impressive stone circle of Calanais (Callanish), which also dates back to the third millennium BC. It is highly probable that there are many other equally important artefacts of the first natives buried deep beneath the peat and earth of the islands of Scotland, but even from what has been found so far, we can tell that a sophisticated culture and widespread trading routes had been established thousands of years before the more recent reputation of the Scots as an ingenious and exceedingly well-travelled people.

The first surviving record of the people who lived in the land that we now know as Scotland came in AD 79 when the all-conquering Romans arrived in Scotland under the general Agricola. In AD 84 Agricola defeated the Celtic tribes who lived in eastern and northern Scotland in a mighty battle in the Cairngorms although we only have the Romans word for how glorious this victory actually was. During the next century the Romans reinforced their position in their most northerly territory by building forts, garrisons, and, in AD 143, the Antonine Wall, which stretched from the River Forth in the east to the River Clyde in the west. The Romans gave the name Caledonia to what is now Scotland. However, whether through choice or their inability to subdue the resistance of the local tribes they encountered, the Romans never succeeded in making Caledonia anything more than a military outpost. In AD 180 the Romans left Caledonia and retreated southwards to Hadrians Wall, in what is now the north of England, never to return. The forts and the Antonine Wall were abandoned, and so ended the first attempt of many to unite the island of Britain under the rule of one empire.

It was the Romans who gave the Celts who lived in Scotland the name of Picts, deriving from the Latin Picti, meaning painted ones, on account of the body paint they wore in battle. And it was the Romans, with their departure from Caledonia, who gave credence to the Picts historical reputation as a warrior people that even the worlds greatest empire could not subdue. Although little is known of the origins of the Picts and their relationship with the other Celtic peoples of Britain and Ireland, the name became associated with the tribes who lived in northern and eastern Scotland. In the centuries that followed the Roman departure in AD 180, the Picts eventually united to establish the kingdom of Pictland. The Picts remained a powerful presence until the 9th century AD, when the kingdoms of the Picts and their principal rivals, the Scots, were first united, but by the following century the Picts had been subsumed into a new Scottish nation and identity, leaving a cultural and political legacy of fierce independence that continued long after their disappearance from history.