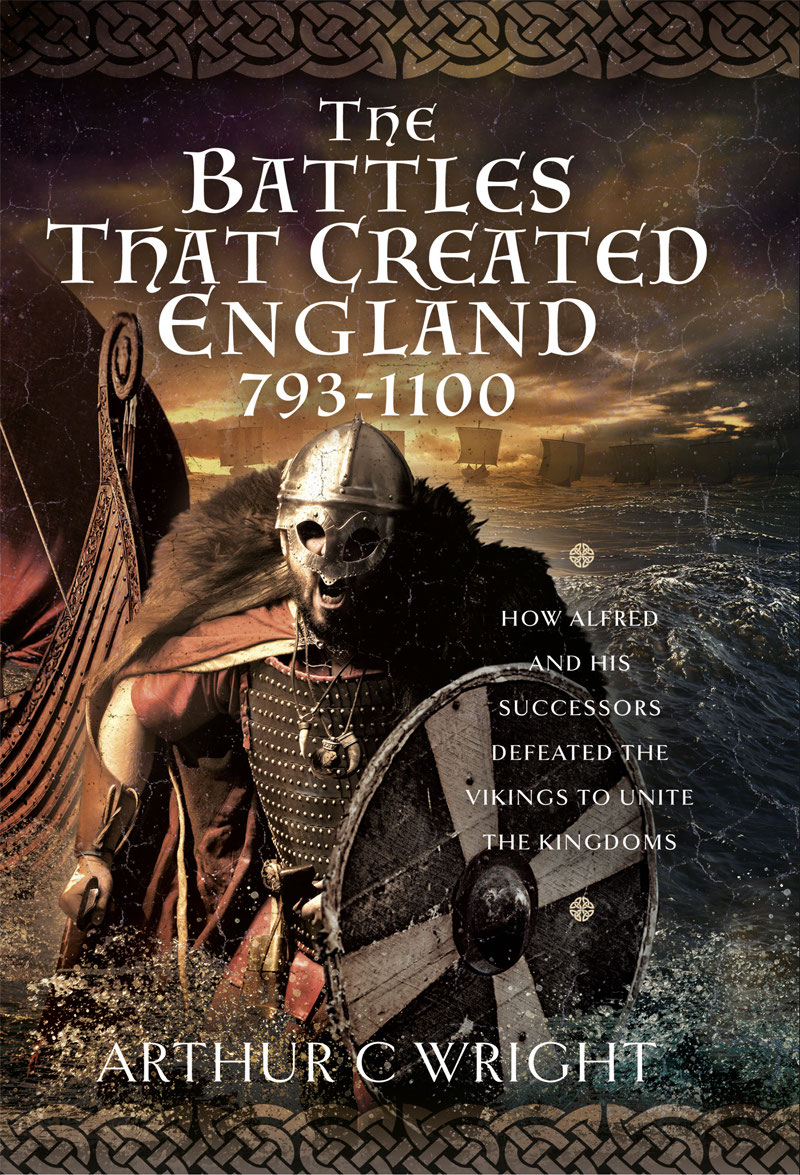

The Battles That

Created England 793-1100

The Battles That

Created England 793-1100

How Alfred and his Successors Defeated

the Vikings to Unite the Kingdoms

Arthur C. Wright

First published in Great Britain in 2022 by

Frontline Books

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Arthur C. Wright 2022

ISBN 978 1 39908 798 8

Epub ISBN 978 1 39908 799 5

Mobi ISBN 978 1 39908 799 5

The right of Arthur C. Wright to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail: Uspen-and-sword@casematepublishers.com

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

For John, who made it all possible.

Contents

Introduction

In the popular imagination, I fear, the warfare of the Dark Ages, the long period dividing Romans from Normans, is not only obscure but unstructured and unimaginative. Battles and conflicts lacked witnesses in most cases and they lacked contemporary evidence and analysis in every case, which tends to relegate them to bloody slogging matches whose participants are imagined as superheroes hacking one another down in a series of individual contacts. Germanic mythology encourages the perception of alpha male legends and inevitably all such battles are divorced from the means of waging warfare as the chroniclers recording them had no concept beyond Divine Will. All this is unfortunate as not all battles require locations or slaughter, the means of obtaining victory are much more subtle than this, and also because, then, the true panorama of history, of failures and successes, is lost in a repetitive and unedifying series of disasters and miseries and so divorced from the important social context.

All too often the particular period of this book, the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries, is presented as a disjointed series of events and invasions lacking coherence or historical structure: sadly too much emphasis has been (and often still is) laid on political constructs that have no relevance beyond the very recent past, certainly they did not exist in this period or for centuries afterwards. The common error of planting present perceptions onto the remote past has therefore denied us the unfolding, if often hesitant, process of unification presented by the several texts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, unification that simultaneously gave birth to ideas of common identity and purpose, this in spite of the necessary fusion of several ethnicities. Yet such is the continuous and coherent story that was set down in the Chronicle, all unwittingly, by our ancestors.

It is therefore not at all surprising if, by comparison, we see the military and social structures, the disciplines and well-documented organisation of the Roman legions, as a separate world of efficiency whose illumination was snuffed out by barbarians at the gates. A rolling fog of ignorance then, apparently, obliterated our historical landscapes until we come to the Norman superheroes who relit both records and culture. This is apparently the view of some writers, whilst others regret the demise of an apparently democratic, but weak and disorganised, bucolic. Yet in spite of this fog of ignorance, we do, from time to time, stumble on amazing and physical treasures, such as Sutton Hoo or the Staffordshire Hoard and then we wonder how this Dark Age could have produced such sophistication. What we fail to ask ourselves is why such ability was not duplicated in other spheres of Dark Age human activity. Well, I think that if we understood these several centuries of conflicts and their battles a little better, we might throw just a little more illumination on the whole indistinct social panorama.

In

AD

410 the Emperor Honorius, in need of even more troops to shore up his tottering empire, issued his famous rescript of the Lex Julia de Vi Publica and withdrew all regular garrisons from Britannia Superior and Britannia Inferior, and with them went all effective civil administration and records. From now on these far-flung provinces were empowered, for the first time, to permit ordinary citizens to bear military arms and to organise themselves into militias. From this point onwards and for many centuries to come Britain (before too long to become England) left behind what semblance she had enjoyed of recorded events, of history; she entered the realms of romance and phantasy. Traditionally we have called these centuries the Dark Ages, for lack of any proper illumination, though their span has somewhat diminished in recent history as modern historians attempt to move the goalposts back to the same end of the field under the light of archaeology.

With the removal of the Roman Army, civil government, administration and bureaucracy ended, for there was no one to train specialists, co-ordinate or pay these servants and a very different society then emerged with the fusion of older and newer societies. Some historians have represented this as a golden age of bucolic egalitarianism set in a rural idyll, others have lamented the end of urban civilisation, whilst popular imagination has revelled in those visions of genocide, rape and arson that sell novels. In truth we know nothing certain about it from written records, hence Dark Ages, but we have a pick-and-mix mass of snippets on which to hang a slowly emerging archaeological picture. Perhaps too often the one colours the interpretation of the other as devotees of one cause (or religion) attempt to reinforce the historical structure that their personal educational path has provided (or political consideration dictated) by daubing archaeology over the gaps.

What finally emerges on the Anglo-Saxon pages of our history books is a society (for few scholars have the courage to argue for mixed societies when facts are so scarce) displaying both wealth and sophistication and no longer reflecting what we had taken to be the Anglo-Saxon bucolic. Instead we see a sudden illumination, though one lacking spotlights, which causes us to look more carefully at the available evidence, and we see a landscape in both physical and political evidences whose emergence is difficult to explain. It is, however, still a world very different from the one that was to follow.