William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2022

Copyright Thomas Williams 2022

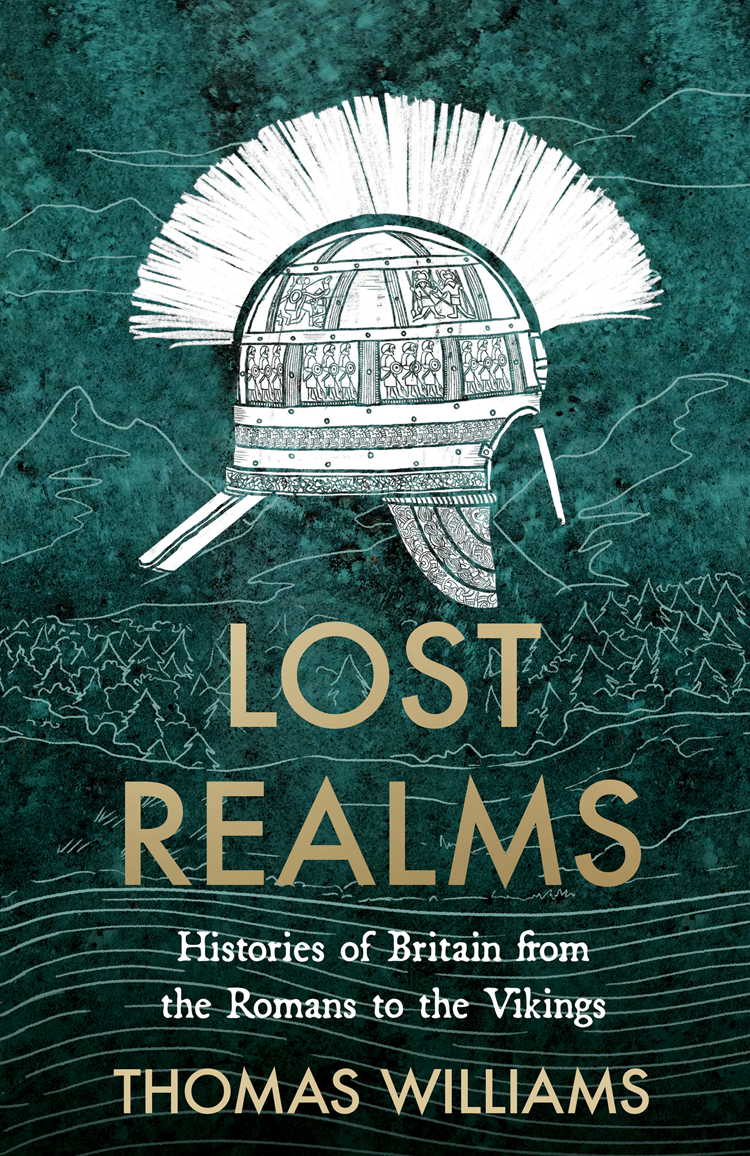

Maps and illustrations by Martin Brown

Cover illustration based on a reconstruction of an Anglo-Saxon helmet based on fragments found with the Staffordshire Hoard. The project was funded by Birmingham Museums Trust and The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent, and is based on a major research project funded by Historic England and the museums.

Extracts from Farmer Giles of Ham by J.R.R. Tolkien (1949) reprinted by permission of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Extracts from Remains of Elmet by Ted Hughes reprinted with permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

Thomas Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Information on previously published material appears

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008171964

Ebook Edition August 2022 ISBN: 9780008171971

Version: 2022-07-15

For my parents

+

MATER OPTIMA MAXIMA

PATER OPTIMVS MAXIMVS

+

Since Brutus came to Britain many kings and realms have come and gone [] What with the love of petty independence on the one hand, and on the other the greed of kings for wider realms, the years were filled with swift alternations of war and peace, of mirth and woe, as historians of the reign of Arthur tell us: a time of unsettled frontiers, when men might rise or fall suddenly, and song-writers had abundant material and eager audiences.

J. R. R. Tolkien, Farmer Giles of Ham (1949)

The natural vice of historians is to claim to know about the past. Nowhere is this claim more dangerous than when it is staked in Britain between 400 and 600. We can identify some events and movements: make a fair guess at others; try to imagine the whole as a picture in the fire [] But what really happened will never be known.

James Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons (1982)

Where now the horse? Where now the men?

Where now the benefactor?

Where now the seat at the feast? Where the hall-joys?

Alas, bright beaker! Alas, burnished warrior!

Alas proud prince! How that time has gone,

dark under nights helm, as if it had never been.

Anon., The Wanderer

It is the middle of the Dark Ages ages darker than anyone had ever expected.

Jabberwocky (1977)

Prologue

Night is falling. Your land and mine goes down into a darkness now; and I, and all the other guardians of her flame, are driven from our homes, up out into the wolfs jaw. But the flame still flickers in the fen. You are marked down to cherish that. Cherish the flame, till we can safely wake again.

David Rudkin, Pendas Fen (1974)

What happens when the rug is pulled, when all the certainties melt away and when what had yesterday felt permanent, unchanging, unchangeable, collapses at breakneck speed? And what comes after?

All ages of the past are dark because the past is a grave. It is a void that historians and archaeologists seek to fill with knowledge with things made by long-dead hands and the ghosts of buildings long demolished, the uncanny traces of people and their lost lives, poignant in their mundanity: a used bowl, a broken glass, a clay pipe, a worn shoe, the pieces of a game scattered and abandoned. It whispers with the words captured on the skins of animals or fragments of birch bark and lines breathed by poets in fire-lit halls, frozen in ink, repeating again and again across the generations, as the bones of their authors crumble in the cold, dark earth. The more we find to fill that void, the better illuminated the past appears. It takes on three-dimensional form in standing buildings and tangible artefacts, detailed reconstructions of costume and paraphernalia. Film and television provide illusory glimpses of the irrecoverable; historical fiction and immersive histories promise time travel to places we feel we might inhabit regardless of their many distortions and omissions. And, by and large, the further away a historical period sits relative to our own lives, the less vital and vibrant it feels the colour footage turns to black and white and then to sepia, it freezes into still photography and then mutates into artist-mediated renderings of life: oil paintings, frescoes, manuscript illuminations, scratches on rock. Eventually it recedes altogether into darkness.

It has become fashionable in recent decades to argue that the trauma of the collapse of the Roman Empire has often been overstated, that for many people life changed little if at all, that the tales told of devastation, plague, poverty and violence were exaggerations, that the archaeological evidence for widespread and rapid civic collapse has been misinterpreted. Historians have always seen the past through the prism of their own age, in the shadow of recent memory, and the last period of relative peace experienced in the West has been remarkable for its overall stability and prosperity. For those in Europe and North America who lived through the world wars and endured the omnipresent spectre of nuclear obliteration, however, the idea that civilizations could be annihilated, that human savagery was limitless and that the lives of individuals and of whole societies could be plunged into existential crisis in a matter of months (or even minutes) was not in doubt. For people in many other parts of the world, the proximity of trauma has seldom been out of sight. And for those who lived through the Middle Ages, death and misfortune were constant companions.

The events of the very recent past, however, have demonstrated with stunning brutality that in the blink of an eye the world can change for ever. What comes afterwards is always unknowable, but the actions and decisions of individuals and societies sometimes spontaneous and sometimes after a prolonged period of anxiety and introspection will set the stage for what will follow: nothing is inevitable about the path the world will take. The clarity with which that is felt in the third decade of the twenty-first century adds a complexion to this book that it did not possess at the outset; some chapters those written later perhaps reflect this more fully that those written earlier, though all are coloured by it to a certain degree. The kingdoms that emerged in Britain in the shadow cast by failing Empire were social experiments in responding to trauma, to the pulling of the rug, and this book is, in part, about how societies facing crisis can find very different paths through and out of it. What emerges more clearly than I had envisaged is the tension between forces that might be imperfectly described as conservative and progressive between those who seek solace and security in the symbols and structures of the past and those who, for good or ill, see potential in the strange and the foreign, abandoning the solidity of stone walls and civilization for something as yet unmade, risking the eradication of older ways of being. Those paths may ultimately converge, but the pain of walking them leaves scars that never fully heal.