About the Author

Mike Pitts is an archaeologist and award-winning journalist who has been the editor of British Archaeology, Britains leading archaeology magazine, for over fifteen years, following and reporting on an extraordinary number of discoveries and scientific breakthroughs. He is the author of Digging for Richard III: How Archaeology Found the King (also published by Thames & Hudson), a gripping account of one of the most sensational discoveries in Britain in the last ten years.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Digging for Richard III

Roman Britain: A New History

The Origins of the Anglo-Saxons

The Tale of the Axe

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

If it werent for the strongly held belief that indigenous Brits are a white race, with a pristine culture stemming from time immemorial, then the debate about immigration could conceivably be a rational one.Instead what we have is an emotional, and emotive, story of threat and invasion.

Afua Hirsch, Brit(ish)

London: Jonathan Cape, 2018, p.298

For Mia

Contents

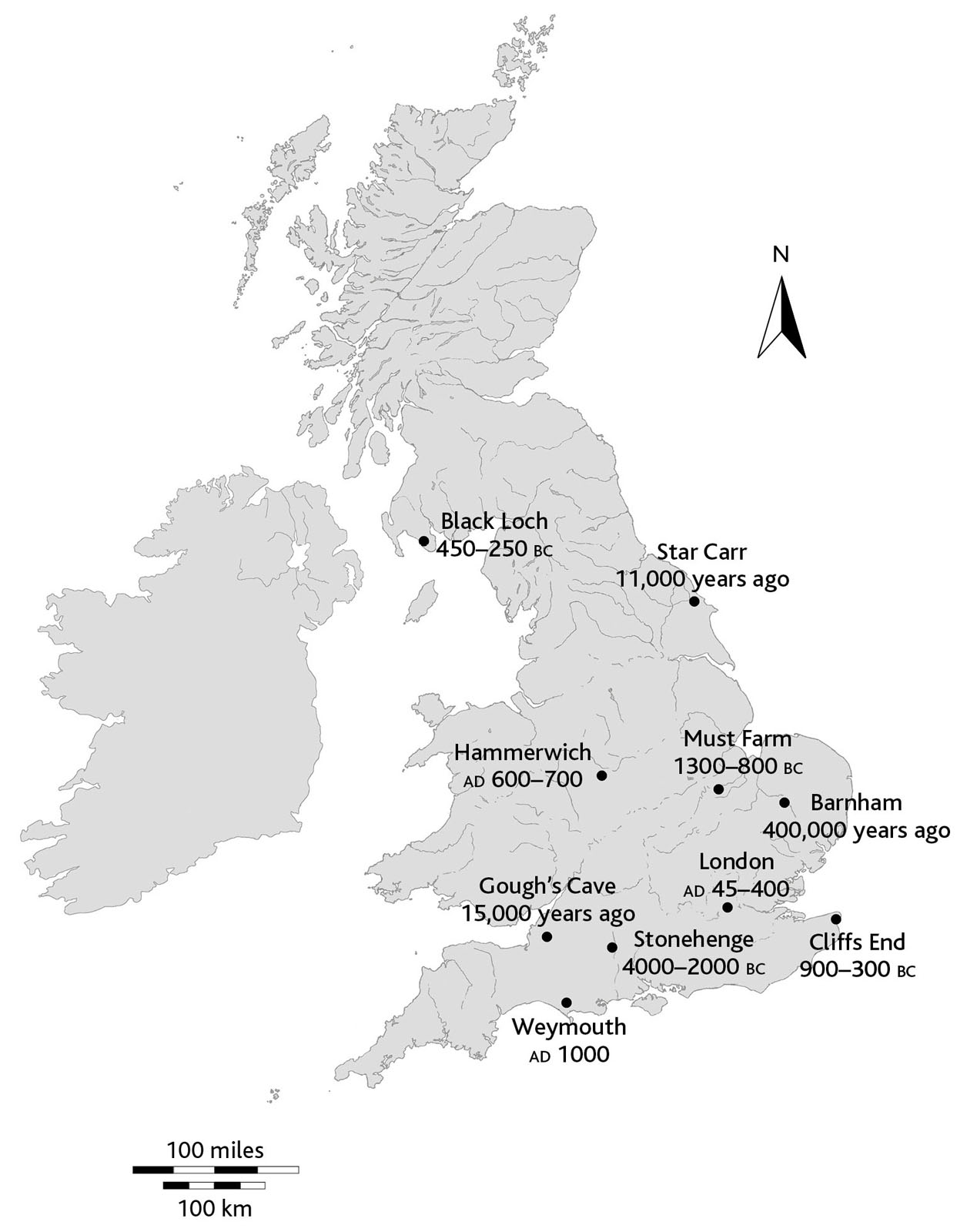

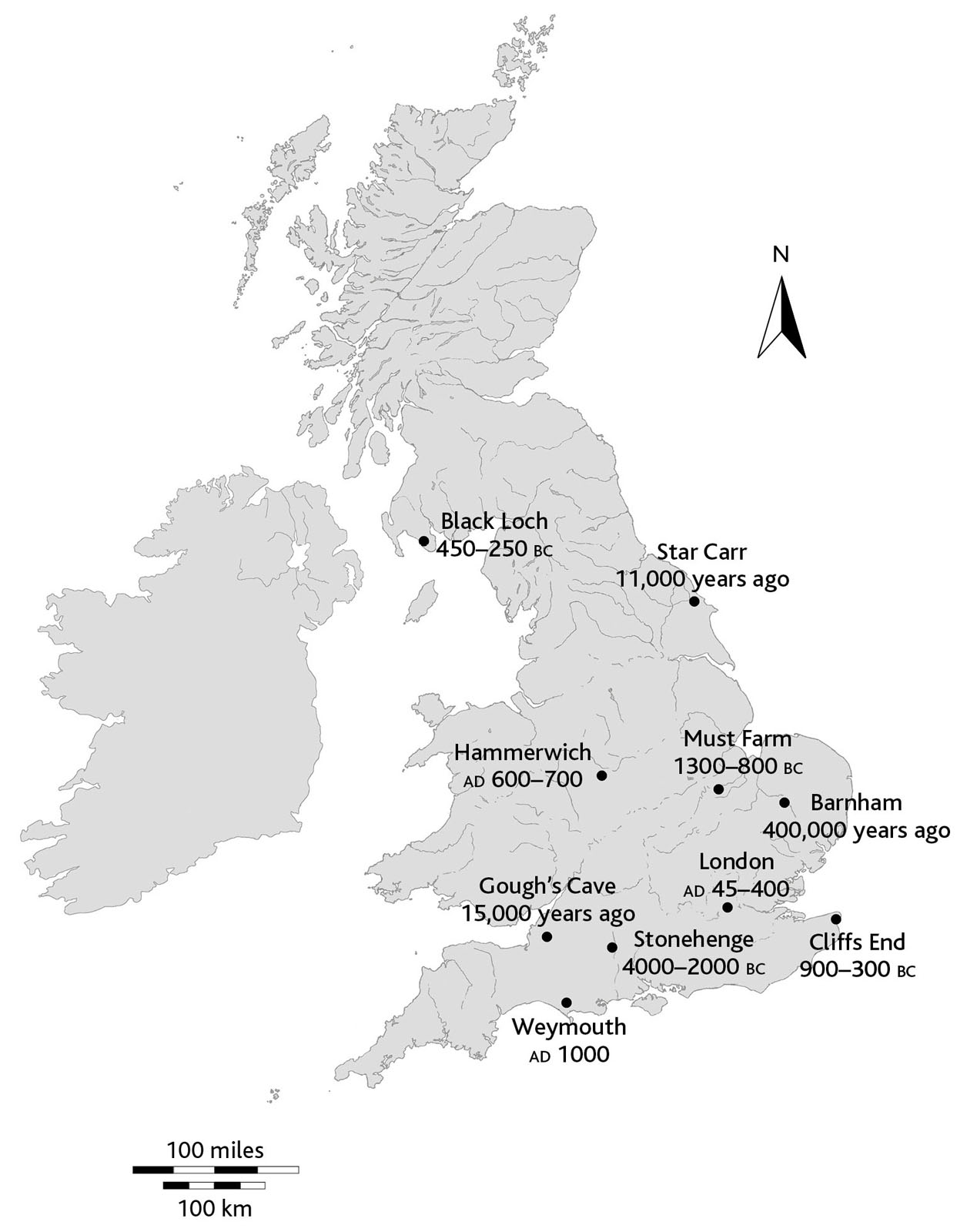

Weymouth, AD 1000

Hammerwich, AD 600700

London, AD 45400

Black Loch, 450250 BC, and

Must Farm, 1300800 BC

Cliffs End, 900300 BC

Stonehenge, 40002000 BC

Star Carr, 11,000 years ago

Goughs Cave, 15,000 years ago

Barnham, 400,000 years ago

A million years of history

When I began studying archaeology, humans were thought to have first reached Britain 200,000 years ago. We now know that people have been here for at least 850,000 years and perhaps 950,000, depending on how we read the evidence. Few archaeologists would be greatly surprised if new discoveries were to show that people have been in Britain for over a million years.

This fivefold increase in the duration of human occupation is extraordinary. It affects not just how we think about early people and the worlds they inhabited, but also our understanding of ourselves, of the paths our ancestors took as they became who we are and our position in the great web of life. We have barely begun even to wonder at the implications.

In recent decades there has been a huge surge in the amount of excavation across the UK so much so that even with an equally impressive growth in the number of archaeologists, there is a shortage of skilled diggers, and we struggle to keep up with new data. And its not just that more stuff is being found.

What we can do with it has been transformed by a continuing revolution in archaeological sciences. New technologies offer previously unimagined ways of learning, with accelerating efficiency and cost-effectiveness, driven by a powerful competitive curiosity at the heart of our universities. In all of this the UK is one of the leading world laboratories for exploring human antiquity.

You might conclude that we can now tell the definitive story of ancient Britain. You would be wrong. If we know anything, it is that there is so much more we dont know. We open a door and see a new world: but all around are a hundred more doors, and we have no idea what lies behind them. We do, however, have the skills to explore further, and to confront more questions. If an outpouring of new data threatens continually to undermine the way we think about the past, this is without doubt the most exciting time to be an archaeologist.

You dont have to be one, however, to share in that excitement. In this book I describe ten different projects, most of which have been headlined around the world, where extraordinary new things are being learnt. Each of them combines a quest for knowledge with revelations that bring us close to individuals who lived long ago. Stories of excavations and discoveries how they happen and the people involved, and what they tell us about the past make compelling detective adventures.

There is also a greater perspective that speaks to us all. Who are we? Where do we come from? What is Britain, and what does it mean to be British? Such questions have acquired a new urgency in an atmosphere of heated debate about the nations relationship with the rest of Europe and beyond, but they are not new. To a significant extent, answers have always come from how we think about our past. Though often perceived as something simple and fixed, it is neither of those things; instead, we see a deep antiquity that reaches back millennia and embraces once unimagined variety and change, in cultures, religions and landscapes, and even human species.

The more people discuss issues of national identity, the more the topic is simplified beyond credibility. That dishonours our story, and diminishes our view of the world. The history once taught at British schools, beyond excursions into ancient Egypt or other lost civilizations, typically began around the time of what is often seen as the last successful invasion, the Norman Conquest in AD 1066. The latest curriculum means children now learn more about what happened in earlier centuries: the youngest are taught about Britain in prehistoric, Roman and Anglo-Saxon times. But as they grow older, learning to use historical concepts in increasingly sophisticated ways, children drop the early stuff. Now their concern is the modern nation and the 20th century, and the longer view, it seems, is not considered an essential part of a modern citizens knowledge.

Yet modern humans people physically and, at least in their capacity for thought, mentally almost exactly like us have lived continuously in the UK for over 10,000 years. Most Britons carry some of their genes, and every one of us carries genes of their distant ancestors. Their cumulative efforts shaped the landscapes we know. Their technological discoveries, and their ideas about beauty, good food and the afterlife, trickled down through the centuries, even as such things changed, which they often did. Their stories, I believe, are important to us today, to our identity and to our place in the world.

The English writer Bruce Chatwin believed that travel, especially on foot, was the essence of being human. Journeying was instinctive, and inhumanities aggression, war, despotism arose when the virtue and dignity of travel were suppressed. Deprived of travel in life, wed aspire to an afterlife of voyaging (ancient Egyptians, he wrote, projected on to the next world the journeys they failed to make in this one).

Its impossible to identify such motivations in antiquity objectively, and we might disagree with Chatwins judgment (in we will encounter a massacre involving some of the most well-journeyed people in world history). But its hard to avoid the extent to which travel, from routine excursions to trading voyages, pilgrimages, migrations and invasions, seems to run through our islands story. Charting and explaining such movements, and understanding their significance, has long been a challenging but essential part of what archaeologists do. In this quest we are now greatly benefiting from new scientific advances, especially in the analysis of isotopes and ancient DNA, which are revealing profound and unexpected stories.

Next page