For

TOBY FOX

and

MALCOLM GIBB

British Peculiarity

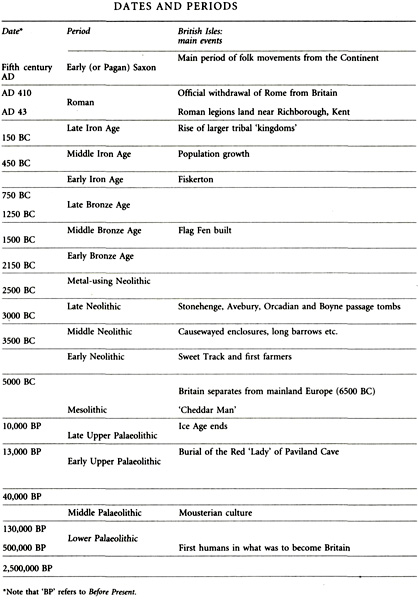

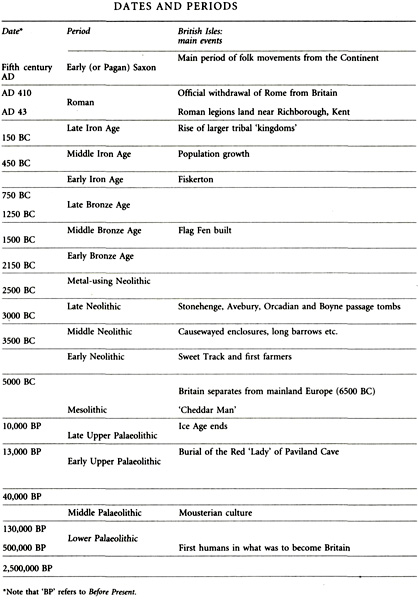

I decided to write this book because I am fascinated by the story that British prehistory has to tell. By prehistory I mean the half-million or so years that elapsed before the Romans introduced written records to the British Isles in AD 43. I could add here that I was tempted to give the book a subtitle suggested to me by Mike Parker Pearson: The Missing 99 Per Cent of British and Irish History but I resisted. In any case, when the Roman Conquest happened, British prehistory did not simply hit the buffers. Soldiers alone cannot bring a culture to a full stop, as Hitler was to discover two millennia later. It is my contention that the influences of British pre-Roman cultures are still of fundamental importance to modern British society. If this sounds far-fetched, we will see that Britain and Irelands prehistoric populations had over six thousand years in which to develop their special insular characteristics.

I regard the nations of the British Isles as having more that unites than divides them, and as being culturally peculiar when compared with other European states. I believe that this peculiarity can be traced back to the time when Britain became a series of offshore islands, around 6000 BC. Those six millennia of insular development gave British culture a unique identity and strength that was able to survive the tribulations posed by the Roman Conquest, and the folk movements of the post-Roman Migration Period, culminating in the Danish raids, the Danelaw and of course the Norman Conquest of 1066. Its in the very nature of British culture to be flexible and to absorb, and sometimes to enliven or transform, influences from outside. Nowhere is this better illustrated than by the historical hybrid that is the English language, which many regard as Britains greatest contribution to world culture.

By contrast, Welshmen from towns on the other side of Offas Dyke are genetically very different from English, Dutch and Norwegian males. Does this mean (as some have claimed) that the Anglo-Saxon invasions of the early post-Roman centuries wiped out all the native Britons in what was later to become England? I suppose that on the face of it, it could, although Id like to see more supporting data, because theres very little actual archaeological evidence for the type of wholesale slaughter such a theory demands. Besides, people have always had to live in settlements and landscapes, which over the centuries acquire their own myths, legends and histories. These in turn may have a profound effect on the incoming component of the local population. Its not by any means a simple business of one lot in and another lot out.

It is difficult to accept that the entire British cultural heritage of England was wiped out by the Anglo-Saxons. Why, for example, did the newcomers continue to live in the same places as the people they are supposed to have ousted, retaining the earlier place-names? It simply doesnt make sense, and we should be cautious before adopting all the findings of molecular biology holus-bolus. Culture and population are not synonymous.

Stories have plots and themes, and I have fashioned this book around what I think are the most important. But inevitably I have had to omit an enormous amount of significant material, simply because it fell outside the immediate scope of the story. However, Britain B.C. is not intended to be a textbook, nor is it in any way comprehensive. Its essentially a narrative and a personal one at that. This is how I see the story of British prehistory unfolding, and I hold the view that a good narrative should be clear-cut, and not cluttered with fascinating but inessential detail.

I would imagine that both of them could wield a mattock quite effectively.

Many archaeological books which purport to be non-technical are written as impersonal descriptions of places and objects that are seldom explained, and are united only by the thinnest of themes. As a result, the public may be forgiven for wondering why so much money is currently being spent on a subject that seems to produce such dreary results. Does it really matter? is a question Ive been asked many times in recent years. Of course I think it does. I believe passionately that archaeology is vitally important. Without an informed understanding of our origins and history, we will never place our personal and national lives in a true context. And if we cannot do that, then we are prey to nationalists, fundamentalists and bigots of all sorts, who assert that the revelations or half-truths to which they subscribe are an integral part of human history. It needs to be stated quite clearly: theyre not. In my view, the main lesson of prehistory is that humanity is generally humane, but from time to time is subject to bouts of extreme and unpleasant ruthlessness. Of course one cannot be sure, but I wonder whether this ruthlessness is perhaps a relict survival mechanism that goes back to our origins as a distinct and separate species, known as Homo sapiens. Whatever the cause, the important thing is that it exists, and we should recognise it, not just in others, but within ourselves as well.

Archaeology as an academic discipline is a humanity, and while there are accepted rules for doing the subject, it is both impossible and, I believe, undesirable to pretend that archaeologists can provide unbiased and objective truth. We all have our own hobby-horses to bestride, and we might as well ride them in public. So Ill come clean. My own background is as a field archaeologist what in the States they refer to as a dirt archaeologist. Its a badge I wear with pride, and this book will inevitably reflect that background. Also, for what its worth, my views on Creation, religion, ideology and the other related topics Ill be addressing in this book are essentially pragmatic. I dont believe in revealed truth, and if Im forced to seek justification for our existence on this planet, I would turn to Darwin before scripture. He at least provided explanations, even if some of them have been superseded by later findings.

Has its insular peculiarity excluded Britain from other, more important relationships with mainland Europe? In 1972, in his book Britain and the Western Seaways, Professor E.G. Bowen attempted to explain the cultures of western Britain and Ireland in essentially maritime terms.

This east-west division of Britain also broadly coincides with the lowland and upland zones (respectively) that the great mid-twentieth-century archaeologist Sir Cyril Fox saw as being fundamental to the development of British landscape and culture what he referred to I tend towards a less closely defined view of these zones. I do not see them as inward-looking or self-referential. Quite the opposite, in fact. To me, the Atlantic/North Sea contrast is just that: its a cultural contrast, not a divide, and is one of the key characteristics of the British Isles. Its a long-term stimulus that has fired the social boilers of Britain and helped ward off complacency.

Before I start in earnest, Id like to express the hope that by the end of this book you will be as convinced as I am that their pre-Roman cultures have made a distinct contribution to the various national identities of the people of the British Isles. I hope you will also agree that the Ancient Britons have lurked in the twilight zone of history for far too long.

Next page