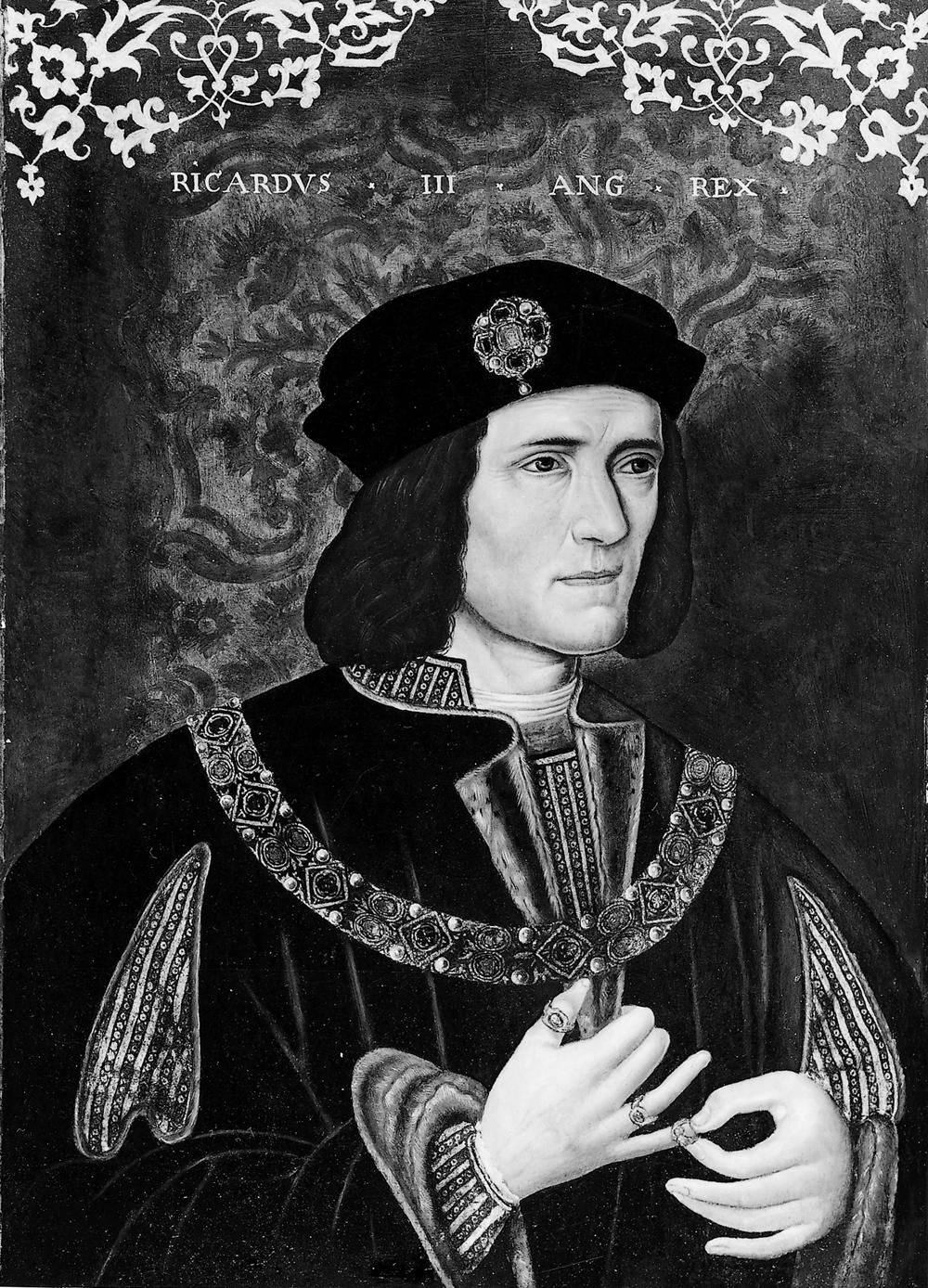

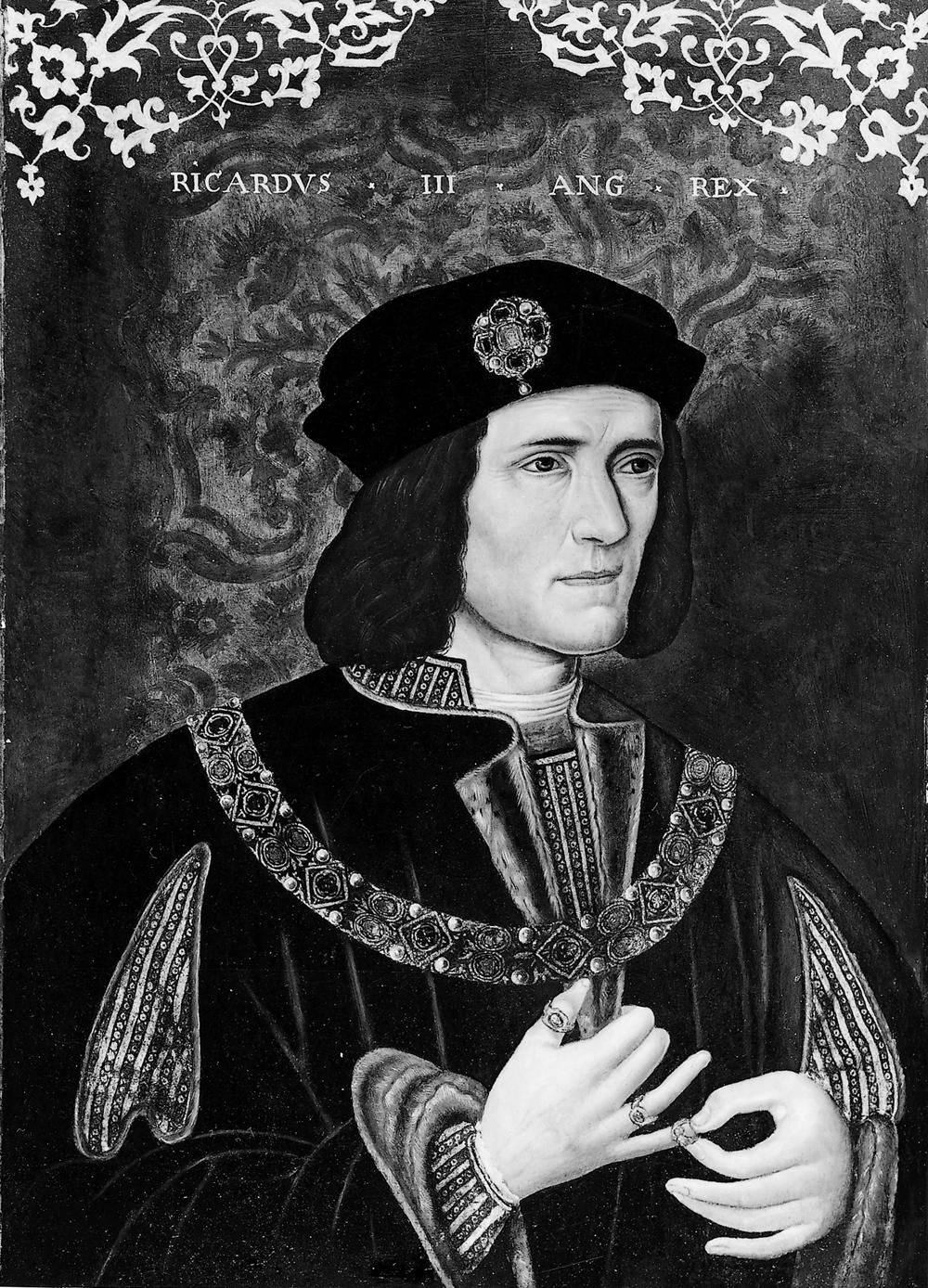

Portrait of Richard III in the National Portrait Gallery, by an unknown artist; thought to date from 1580 to 1600, it is close to a portrait in the Royal Collection that may have been the prototype for nearly 20 known paintings. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

About the Author

Mike Pitts is an archaeologist and award-winning journalist. He grew up in Sussex and studied archaeology at University College London. In his early career he directed his own excavations at sites such as Stonehenge and Avebury, and he continues with scientific research, including most recently on an Easter Island statue. For the last ten years Mike has edited Britains leading archaeological magazine, British Archaeology, and as a freelance journalist he writes frequently for national and international newspapers and magazines.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Crown Jewels

The Medieval World Complete

The Medieval World at War

Power and Profit: The Merchant in Medieval Europe

Englands Forgotten Past:

The Unsung Heroes and Heroines, Valiant Kings, Great Battles and Other Generally Overlooked Episodes in Our Nations Glorious History

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

In which events of the Wars of the Roses are summarized, and we begin to ask why Richard III inspires such strong interest

In which we visit Leicester, discover how a city remembers Richard III, meet Richard Buckley and Philippa Langley, and learn of the origins of Philippas quest to find a kings remains

In which Philippa Langley approaches University of Leicester archaeologists, who research the history of the Greyfriars site and confirm that Richard IIIs grave may still be there

In which Richard Buckley plans an excavation in Leicester, Philippa Langley solves a late funding crisis and Mathew Morris prepares to direct a dig

In which an excavation is launched in a car park, and archaeologists find a friary, a church and a human skeleton

In which a skeleton is excavated

In which various scientific studies are conducted on a skeleton to establish age, gender, height and build of the individual, details of diet, health and pathology, and approximate date of death

In which scientific, historical and artistic research together establish the cause of death and the identity of a person represented by a skeleton

In which we consider why finding a kings remains matters, assess what happened after the revelation, and describe how the site was found where the Battle of Bosworth was fought

For Nicky

The dead do not come back to complain of their burial.

It is the living who are exercised about these matters.

Thomas Cranmer comforts Henry VIII, who has dreamed about his dead brother Arthur. Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall

What we are about to tell you is truly astonishing.

On 4 February 2013, a team from the University of Leicester delivered its verdict to a mesmerized press room, watched by media studios around the world: they had found the remains of Richard III, one of the most disputed monarchs in British history.

This is the story of how that happened.

The discovery, as Richard Buckley, the lead archaeologist behind the project, said, was an astonishing achievement.

Richard III is both a historical figure at the centre of dark and bloody events signalling the end of the Middle Ages, and an enduring mythical ogre, captured by Shakespeare as the archetypal villain. He is a man whose almost psychotic ambition holds a fearful fascination. Or, it may be, he is a maligned king whose noble progress was cut short and then concealed by those who would distort history for personal gain.

His very life embodies terror and conspiracy. It demands precise analysis, the uncovering of truth and the exposure of falsities. How appropriate, then, that the most forensic of historical practitioners, scruffy, mud-spattered archaeologists in league with futuristic scientists, should uncover the physical remains of the protagonist himself. Fragile, delicate and intimate, Richard IIIs bones are hard evidence that few had expected ever to see.

Yet improbable as the discovery was, this success was not the only remarkable thing about the project. In my career as an archaeologist and writer, I have seen, studied and reported on more excavations than I can remember; I have worked on many myself, and even directed a few. But never have I witnessed an excavation like the one that found Richard III.

It was well planned, as all good excavations are. It had precise goals, again a sign of a field project likely to deliver results. But here events parted with normality.

The dig began on a Saturday in August 2012. The team had five objectives, and two weeks in which to achieve them. What typically happens in such situations is that discoveries are made that go some way towards solving the problems the archaeologists have set themselves. But other finds, as you might expect, raise new questions. At the end of the dig, the archaeologists pack up their things and anticipate the long process of analysis always much longer (and more expensive) than the actual dig and feel already they now know more than they did. But they also know there are new things they dont understand. There is a sort of balance, with old, partly solved questions on one hand, and new questions to answer on the other. If funding bodies will permit, they will have to come back and dig again in its way, of course, an achievement in itself. They enjoy digging.

The excavation in Leicester was not like that. The archaeologists achieved their first objective on the first day. This had been considered in advance to be a reasonable expectation, though no one would have bet on pulling it off on day one. It took a little longer to achieve objective two (a probability) nearly a week. They ticked off objective three (a possibility) on the eighth day, four (an outside chance) on the twelfth, and five (not seriously considered possible, with Richard Buckley having promised to eat his hat if it happened) on the same day as four. Two objectives in one day! And they still had two days of digging left.

The excavation had been commissioned by Philippa Langley. Philippa is not an archaeologist, but a writer with an interest in history and a passion for Richard III. Before they began, the team had warned her not to be too hopeful. There was only one thing she really wanted from the project: to find the remains of Richard III. This was the objective the archaeologists judged, in plain speaking, to be impossible. Yet when the digging began, it seemed, anything might happen.

People would find things, Philippa told me, not just every day but really almost every hour. Every moment, we would hear a shout saying, Look at this! And wed all be running to see what it was, and then wed be running to the other side to see something else that had been found.

This was fun. They were sitting down in the tent having lunch, and Philippa said to the diggers, God, I love your job. No wonder youre archaeologists!

A ring of bemused faces looked up from their sandwiches.

This is just the best job in the world! Philippa repeated. If Id known it was like this, I might have been an archaeologist!

Next page