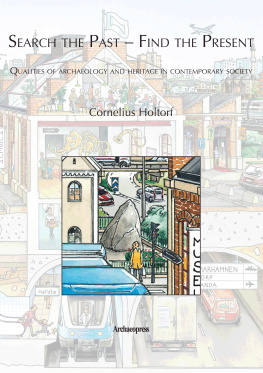

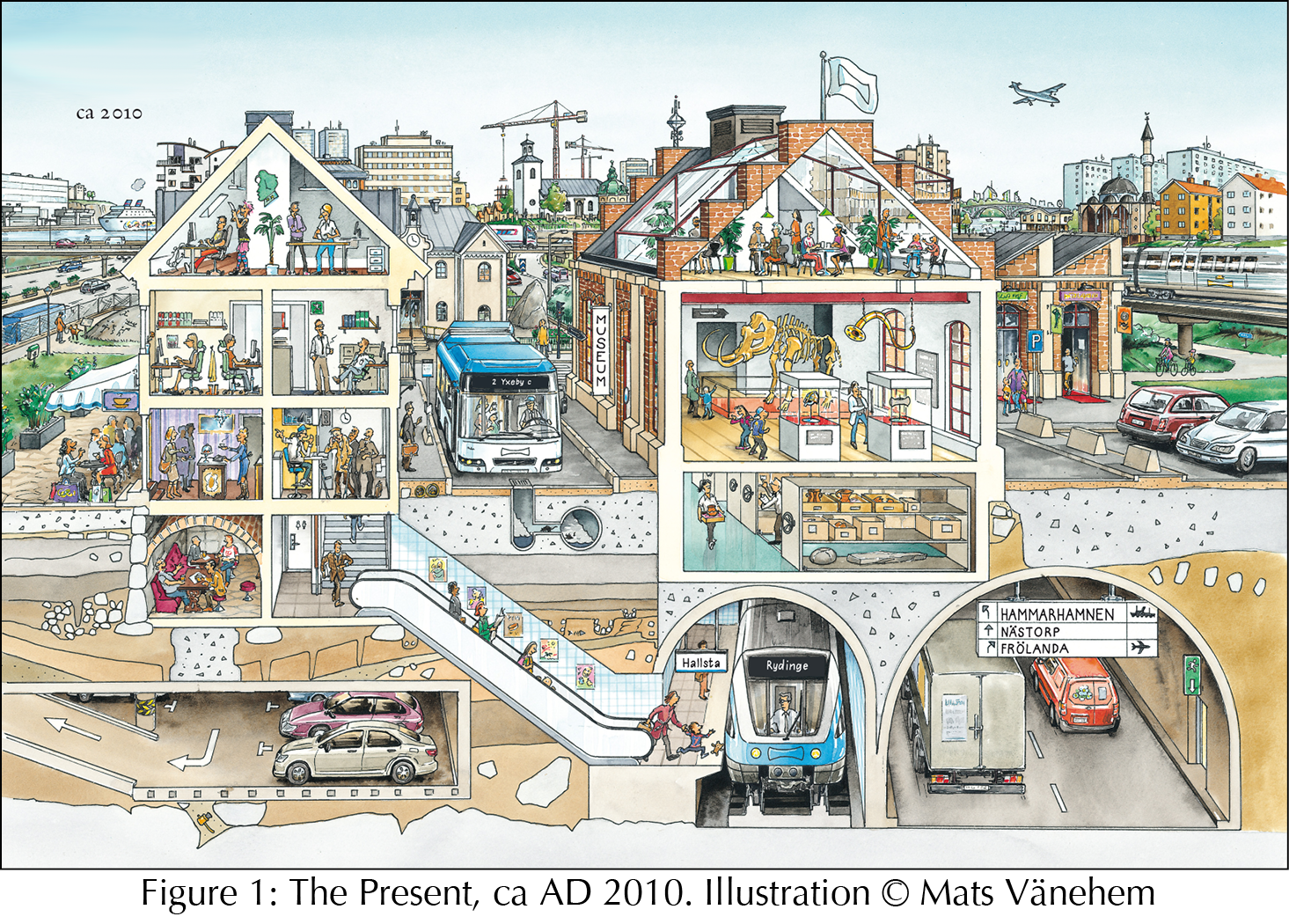

Here is an image full of pertinent details. It was drawn by Mats Vnehem, an illustrator and archaeologist at Stockholm County Museum in Sweden. The image is taken from Vnehems book Hitta historien (2010) published by Bonnier Carlsen, one of Swedens leading publishers of children literature. In English, the title of Vnehems book means as much as finding the history. But it could also be understood as a request to find the history! This image will accompany us throughout this book.

Vnehems work consists for the most part of ten large images, each one stretching across a double page. They depict snapshots of Swedish prehistory and history, from the Ice Age to the present:

the Ice Age (ca 10,000 BC),

the Mesolithic (ca 8,000 BC),

the Neolithic (ca 3,000 BC),

the Bronze Age (ca 900 BC),

the Migration Period (ca AD 400),

the Viking Age (ca AD 1,000),

the Middle Ages (ca AD 1350),

the Age of the Swedish Empire (ca AD 1690),

the Industrial Age (ca AD 1890), and

the Present (ca AD 2010), which is the image reproduced as Figure 1.

Each image shows the same place from the same vantage point, although at different points in time and with significant historical changes occurring between one image and the next. The scenes depicted are all full of detail. You see human beings engaging with one another, you see their buildings, their material possessions, their material remains, as well as a good bit of geology. In the earlier images you also see a lot of flora and fauna. At the end of the book, Vnehem briefly describes each image, the historic reality it represents and the archaeological record left behind. There is also a chronological table. In this way, Vnehem does justice to his educational ambitions of his work.

The point of his work is that, by moving from one image to the next, you can trace every time periods deposits in slowly accumulating and occasionally diminished archaeological layers. Pits, basements and even batchers reach down and destroy older layers, as do modern underground tunnels and car parks. Some archaeological artifacts are later re-discovered, while others remain for now in their original positions.

Hitta historien finding the history allows Vnehems young readers to observe how each period, in clearly stratified contexts, leaves its own distinctive material traces on top of those of earlier periods. It is about discerning how each period, including the present, transforms the landscape and builds a new layer of habitation on the existing archaeological record of earlier times. This corresponds nicely to the concept of landscape biographies, which has been applied and theorized particularly coherently in recent Dutch archaeology (e.g. Roymans et al. 2009). History, according to this concept, is found by studying the variety of material traces from different periods that occur in the landscape.

Find the history! is a more urgent request to the reader, corresponding to what is commonly demanded of professional archaeologists. They are expected to discover the past by recovering and analyzing its material remains. These remains are said to form part of the archaeological record, and to a large extent they are found underground. Archaeologists are obliged to describe and explain the course of human history by studying the archaeological record. This, then, is what the reader of Vnehems book is expected to do as well: Experience, discover and become curious about the past it is almost like being a real archaeologist, as the back cover has it. Just do it find the history!

In this view, there is quite clearly only one past, the past that really happened. Archaeologists search in the present for material evidence, which they then study in order to reconstruct that past and thus write history. However, archaeology does not occur in a vacuum. In many ways, archaeology reflects and is embedded in present-day society (Mongait 1985 [1963]; Himmelmann 1976; Keller 1978). There can be no doubt that for Mats Vnehem too, archaeology is a contemporary undertaking of eminent social significance.

Just look at the museum displaying ancient artifacts and Ice Age mammoth bones. The entire exhibit is inevitably very much of its own time, presumably depicting the history of one or more archaeological cultures and ethnic groups or possibly the origins of the nation. By the same token, the collection stored in the basement mirrors the present, not only insofar as it appears to be ordered systematically according to a conventional logic of material and period of origin but also insofar as it is housed in those space-saving archive shelves characteristic for our time and presumably kept in climate-controlled conditions which we believe benefit conservation.

And do you see that rock art site in the background neatly displayed as a heritage site, with a little information panel educating curious visitors about the past in which the rock art originated? I suspect that we all have seen many such sites in our surroundings or while travelling. They attract tourists and inspire artists; they are the topic of popular books and are used in marketing campaigns; they are studied by professional and amateur archaeologists alike, in each case reflecting values and meanings of our own age.

If all this seems self-evident and you are wondering what I am getting at, let me now tell you that in my view, depicting history, archaeology, heritage and society in the way I just described is a mistake.

Society is not merely the contemporary context within which archaeology and heritage take certain forms and acquire meanings to the extent that they reveal or represent the past. Present-day society is not merely the culturally and economically most suitable uniform or depending on your perspective most suitable straight-jacket of an academic discipline and its empirical data. Contemporary interest groups are not merely audiences and possibly disseminators of insight and knowledge about the past delivered by archaeologists. Consequently, academic archaeology and the material remains of the past would in their essences appear to be timeless and seemingly exist irrespective of the specific context of any one society (e.g. Bazelmans 2010). I wish to disagree with this view.

There is no single past waiting to be revealed by the practices of scientific archaeology and history. The material remains of the past do not mean anything themselves. There is no archaeology and no data-set independent of culture, society, and its associated practices. The meaning of the past and its remains cannot be revealed objectively, but are always created in a given contemporary social and cultural context (Barrett 1994: 168170).

I would like to argue that the objective existence and character of the archaeological record below the surface is not a precondition for archaeology but, in fact, the precise opposite. The archaeological record as we know it today is a result and consequence of our way of practicing archaeology. Key notions like the archaeological record, objectivity in recording, classification of artifacts and periods, and the stratigraphic method; ambitions to trace the lives of human individuals of the past, to reconstruct ancient cultures and landscapes in relation to ethnic groups and national heritage, to conserve ancient remains, and to educate the public about archaeology and the past all these notions of practices that steer much of contemporary archaeology are in fact neither given nor self-evident (Lucas 2001; Thomas 2004).