Archaeology Hotspot Great Britain

Archaeology Hotspots: Unearthing the Past for Armchair Archaeologists

Series Editor: Paul G. Bahn, independent archaeologist and author of The Archaeology of Hollywood ()

Archaeology Hotspots are countries and regions with particularly deep pasts, stretching from the depths of prehistory to more recent layers of recorded history. Written by archaeological experts for everyday readers, the books in the series offer engaging explorations of one particular country or region as seen through an archaeological lens. Each individual title provides a chronological overview of the area in question, covers the most interesting and significant archaeological finds in that area, and profiles the major personalities involved in those discoveries, both past and present. The authors cover controversies and scandals, current digs and recent insights, contextualizing the material remains of the past within a broad view of the areas present existence. The result is an illuminating look at the history, culture, national heritage, and current events of specific countries and regionsspecific hotspots of archaeology.

Archaeology Hotspot Egypt: Unearthing the Past for Armchair Archaeologists , by Julian Heath (2015)

Archaeology Hotspot Great Britain: Unearthing the Past for Armchair Archaeologists , by Donald Henson (2015)

Archaeology Hotspot Great Britain

Unearthing the Past for Armchair Archaeologists

Donald Henson

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB, United Kingdom

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-0-7591-2396-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7591-2397-7 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Introduction

T his book is a description of the archaeology of Great Britain. It covers not only some of the major archaeological sites, but also some of its archaeological personalities and debates. Archaeology reveals a great deal about peoples lives and about the great changes that have occurred since the island was first settled nearly one million years ago. For those not familiar with British archaeology, there is much that will fascinate. For those who already know something about the island and its past, there will be much that will be new to discover.

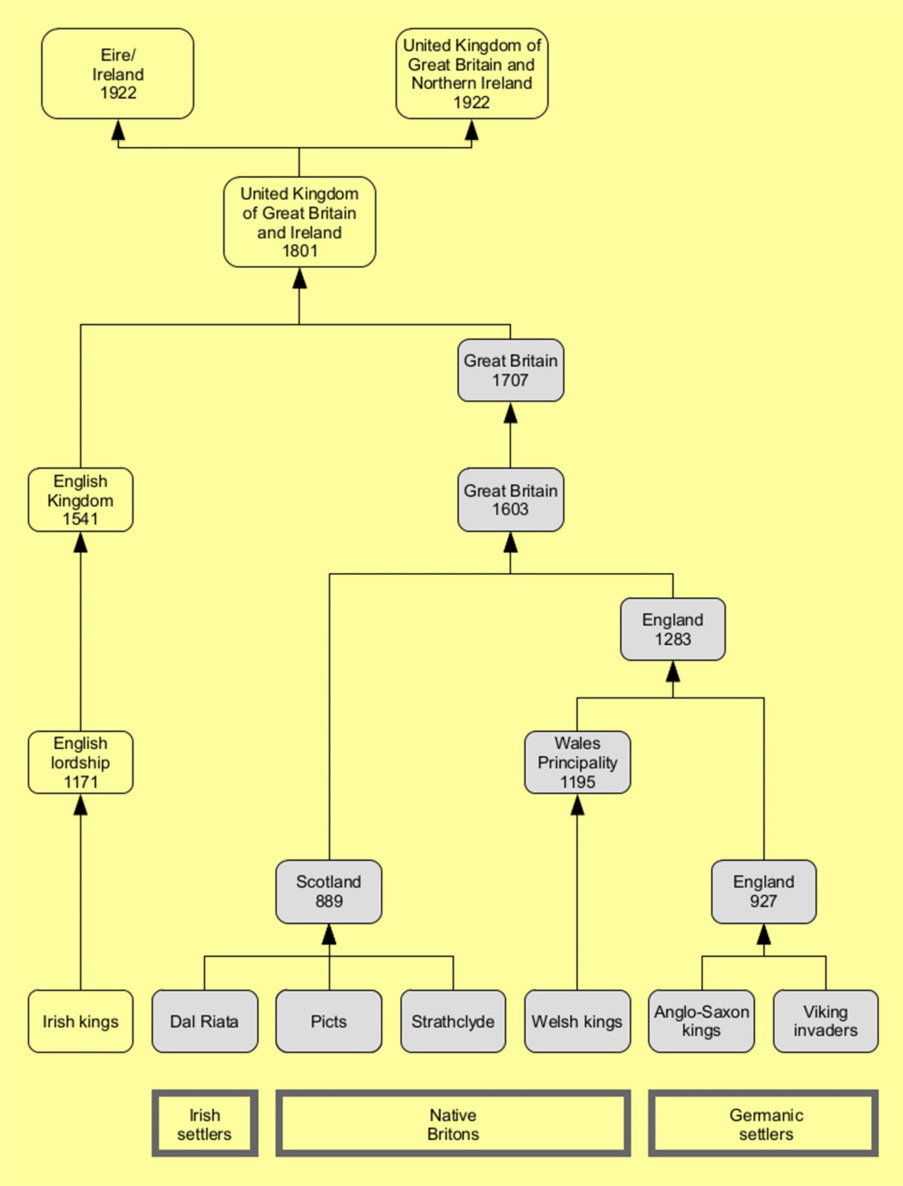

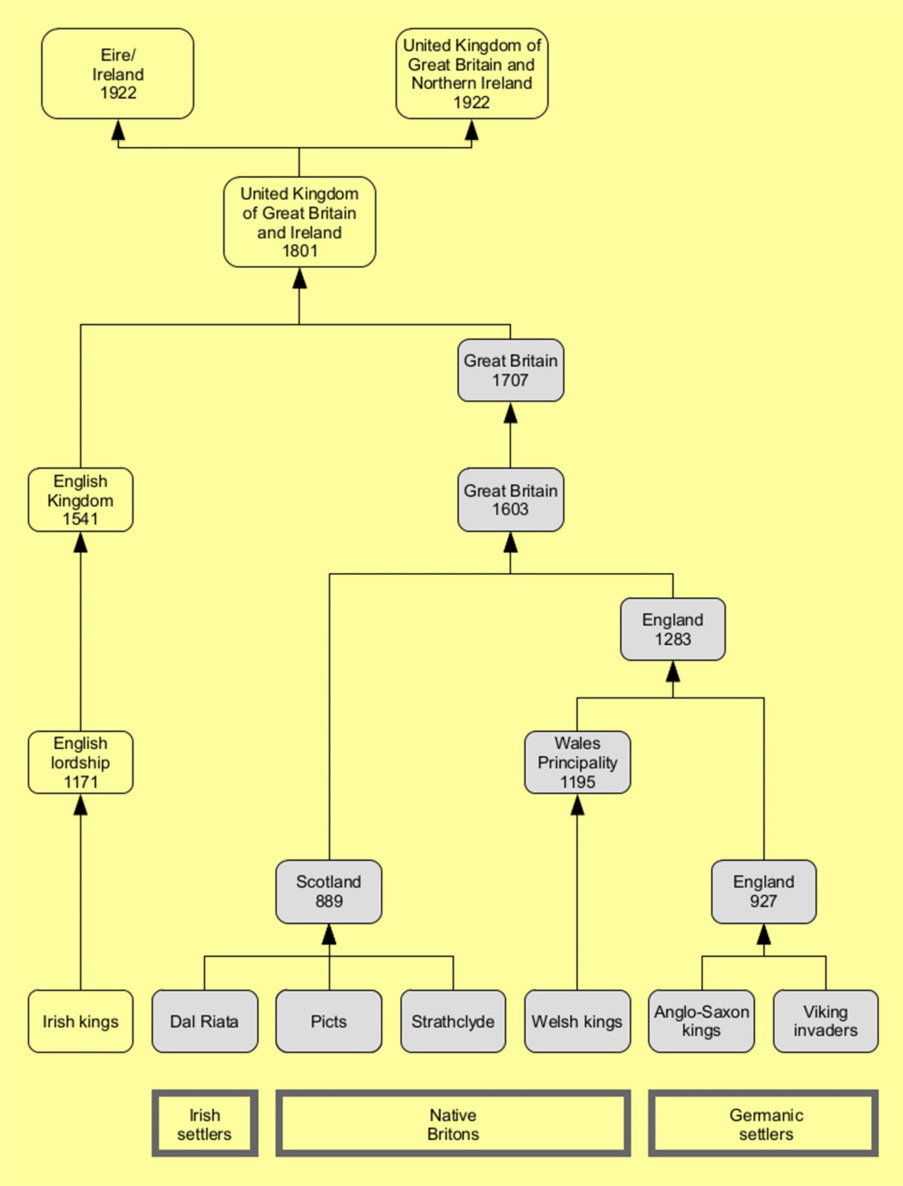

We must begin with a word about names. This book covers the archaeology of Great Britain. Strictly speaking, Great Britain does not exist as a nation. It is part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland is not covered in this book. Its archaeology is shared with the Republic of Ireland and has little in common with that of the rest of the United Kingdom. The three parts of Great Britain are England, Scotland, and Wales, each of which had their own origins in the earlier Medieval period. England conquered the Principality of Wales in 1283, and absorbed it fully within England in 1536. In 1603, King James VI of Scotland succeeded to the Kingdom of England as King James I. His combined kingdoms were informally known as Great Britain, but were not united under one government and parliament until 1707. It ceased to exist as a nation in 1801 when it merged with Ireland into the United Kingdom (southern Ireland became an independent nation in 1922). Today, both Scotland and Wales have their own parliaments and governments handling internal affairs underneath the parliament of the United Kingdom. England has no parliament of its own. It is governed directly by the government and parliament of the United Kingdom.

The formation of Britain, courtesy of Donald Henson

Why Great Britain? Is this a symptom of pride, or a claim to status? No. The name Great Britain was first used by the ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy in 140 AD to describe the bigger of the two main islands in what were already called the British Isles. Ptolemy described the smaller of the two (Ireland) as Little Britain. Most people now use the simple term Britain as a geographical term to describe the island and reserve Great Britain to describe the political union of England, Scotland, and Wales.

The fact that Great Britain is divided between three governments and parliaments is important for how archaeology is practiced in its three parts. There are now legal differences between how archaeology is carried out and in the laws and organizations governing the heritage of each of the three nations. However, Britain as an island has a long history and prehistory shared between the three nations before their creation in Medieval times.

The most important features that define British history and prehistory are its long-time depth of human settlement, its geography, and the diversity of the ways of life and cultures of its people. Britain has a history of continuous settlement since the last Ice Age, and of sporadic settlement by early hominins long before this (at least 800,000 years). Its landscape is littered with the remains of deep time, with later remains superimposed upon earlier. It takes a skilled eye to be able to disentangle this long history in which a village may contain buildings of the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries and have nineteenth century fields created on top of early Medieval fields and lying below uplands with traces of late Iron Age and Roman period settlements and fields. No part of Britain is free of the imprint of man, even the natural landscapes are not as they appear.

As an island, Britain has a long coastline with many navigable rivers. Most of Britain has easy access to the coast and the movement of people and goods is possible over long distances by ship and boat within easy sailing distance along the Atlantic coast, across the Channel and the North Sea. It is also close to Ireland and was once physically joined to the continent and still lies close to the rest of Europe. Britain has always been open to foreign migration and settlement, able to trade widely with the rest of Europe and absorb foreign influences, albeit sometimes under protest. The English Channel and North Sea also act as a moat effectively defending Britain against all but the most determined of invasions. Compared with most other lands, Britain has been only seldom affected by conquest.

The mainland of Britain is 600 miles long from Lands End in the south to John OGroats in the north. To the southwest lie the Isles of Scilly and to the north the Orkney and Shetland Islands. Its greatest width is 330 miles from Cornwall in the southwest to Kent in the southeast. The island is cut by major rivers and estuaries. The Clyde and the Forth neatly divide Scotland into north and south. The Rivers Tweed, Tyne, and Tees shape the south of Scotland and the northeast of England. The major rivers of Yorkshire feed into the estuary of the River Humber that separates northern England from the south. The River Severn rises in Wales and flows in a long loop into the Severn estuary, separating south Wales from southwest England. The River Thames flows west from London to form the northern border of the ancient kingdom of Wessex.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.